Foundation School enlargement and later history

Contributed by Survey of London on Aug. 24, 2017

Alterations and enlargement of the Davenant School in the 1890s were

occasioned by changes to the wider administrative framework for education. The

formation of the Charity Commissioners in 1853 led to amalgamation of

Whitechapel’s parish charities and the building of a Whitechapel Charities

Commercial School on Leman Street. The Education Act and three Endowed Schools

Acts of the years around 1870 and growing demand for school places were

further backdrops to protracted discussions between the Whitechapel Trustees

and the Charity Commissioners. Eventually in 1888 the Whitechapel Charities

(embracing St Mary’s School and the Leman Street School) and the Davenant

School were merged to form the Whitechapel Foundation, unified in adhering to

Church of England religious instruction and amply provided for by historic

charitable endowments. What had been Davenant’s Endowed Free School on

Whitechapel Road, which had gone through a rocky period, was henceforward the

Foundation School, a secondary school for 250 boys which was to be improved

with new buildings (and a specified need for a chemical laboratory and

workshops). The elementary schools were now, confusingly, called the Davenant

Schools.

With the new scheme settled, meetings chaired by the Rev. A. J. Robinson in

1888 quickly approved plans for new buildings by Frank Ponler Telfer, the

24-year old son of one of the new Foundation’s Governors, John Ashbridge

Telfer, a pawnbroker of 88 Whitechapel High Street. Another Governor was John

Ashbridge, a solicitor on the south side of Whitechapel Road and the brother

of Arthur Ashbridge, the District Surveyor for Marylebone who on occasions

also acted as a surveyor for the Whitechapel Foundation. They were cousins to

John Ashbridge Telfer. Their fathers, John Simpson Ashbridge and Somerville

Telfer (who married Maria Ashbridge), and grandfather, John Ashbridge, had all

been East London pawnbrokers. John Ashbridge and J. A. Telfer were the only

Governors besides Robinson to attend a meeting with the Charity Commissioners

in July 1888. The young Telfer, whose mother Mary Ann was the daughter of John

Ponler, a Wapping timber merchant, identified himself as a surveyor. He had

served an apprenticeship in the City with George Andrew Wilson, architect and

surveyor, during which the firm, as Wilson, Son & Aldwinckle, had overseen

alterations to the Duke’s Head public house (181 Whitechapel Road) in

1881.

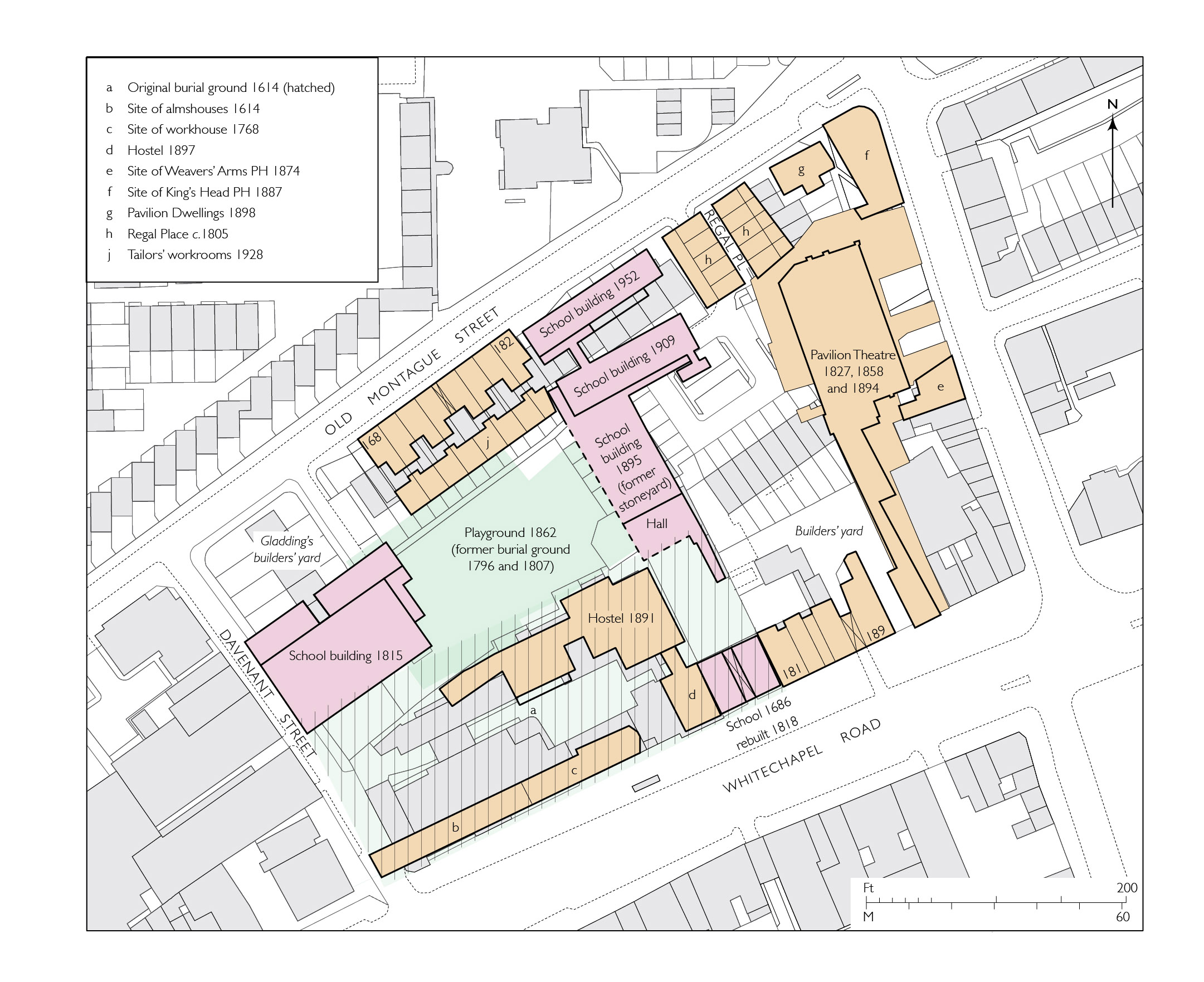

A first complication to arise in 1890 was to do with the loss of light and air

to the west with the building of the Victoria Home. Arthur Ashbridge dealt

with this and Telfer prepared new plans for what was to be called a Commercial

School, now working with a new headmaster, Henry Carter. In 1891 the Governors

split five to four against a new roadside building and in favour of a new

building in the ‘garden’ (the playground and former burial ground), envisaging

the road frontage being freed up for shops. Land along Old Montague Street was

purchased to supplement what was already owned through the William Rowland

Charity and four courts of houses were cleared. On behalf of the Charity

Commissioners Ewan Christian approved building in the playground, seemingly

unaware that this would contravene the Disused Burial Grounds Act; his

suggestions were otherwise bypassed. In 1892 nine firms of architects were

invited to submit anonymised plans for a building behind the old school on the

playground, to be on ‘columns and girders’ for an open ground floor so as not

to lose the play space. Five schemes were received. That by Telfer was

selected as the best, his father being one of the four inspectors. John C.

Hudson and Herbert O. Ellis placed second and third respectively. Telfer

worked up his scheme in 1893 and building work ensued in 1894–5 with J. S.

Hammond and Son of Romford as contractors. Telfer was asked to ensure that

‘The East London Commercial School’ should appear in the floor and that a

tablet should commemorate the governors. But the Charity Commissioners

disapproved of the name and insisted on the Whitechapel Foundation School.

Fitting out followed in 1896. Already in 1898 most of the sixth-form boys were

of Jewish origin, fathers being teachers of Hebrew, a furrier, waterproof

manufacturer, butcher, tailor, and poultry and horse slaughterers, coming from

as far as Stoke Newington, Camberwell and Upton Park.

Stylistically ‘splendid Neo-Jacobean’, perhaps influenced by E. W.

Mountford, Telfer’s two-storey building is of red brick with terracotta

dressings, including mullion and transom windows, some with leaded lights, and

scrolled gables. The brief forced formal ingenuity and resulted in a

distinctive parti that is something of an architectural statement, albeit

devised from Board School precedents. Telfer was evidently accomplished, but

despite this youthful opportunity his career did not take off. He identified

himself in 1901 as an auctioneer, no longer a surveyor. He died in 1907, age

43. The ground-floor covered playground was outwardly articulated by arcaded

piers. Within, there were cylindrical cast-iron columns and composite girders

to support the superstructure. The five-bay east–west assembly hall is grandly

gabled – an intended flèche was vetoed by Christian. It has an arch-braced and

barrel-vaulted wagon ceiling with turned tie beams and king posts. The south

façade was visible from the passage through the old building across a now

cleared yard, and the hall was approached by an eye-catching covered staircase

with a stepped open arcade. This had been designed to be central, but was

moved to the east bay and given a lobby at its head at the building

committee’s suggestion, presumably for the sake of a larger yard. A nine-bay

north–south range housed six classrooms and staff accommodation.

The LCC and the Board of Education imposed alterations and the addition of a

Neo-Georgian north range parallel to Old Montague Street in 1908–9. Designed

by Arthur W. Cooksey, this provided four more classrooms, a physics laboratory

and an art room. There was no space or money for a gymnasium, but an enclosed

fives court was added in 1915–17. This seems to betoken a consciousness of

status in what became the Davenant Foundation School in 1928. This was,

however, one of the smallest secondary schools in London and the only one

unable to provide hot dinners. At the behest of the LCC, negotiations for an

amalgamation or a move away from Whitechapel began in 1937, but these were

interrupted by war and evacuation. There were wartime alterations to the front

range for use as a rescue centre. In the early 1950s voluntary-aid grammar-

school status was granted and, despite a falling roll, a new range was added

along Old Montague Street for a biology lab, library and two additional

classrooms. Meanwhile, in the face of a decreasing local population, the LCC

planned comprehensive redevelopment of the area.

The school moved to Loughton, Essex, in 1965, a shift first suggested by the

Ministry of Education in 1956. The GLC’s Inner London Education Authority took

the Whitechapel site and up to 1971 it was used for Walbrook College’s East

London College of Commerce. The Victorian Society, Ancient Monuments Society

and GLC Historic Buildings Division resisted a plan for clearance behind the

already listed front building, use as a youth centre being suggested. This led

to the listing in 1973 of the assembly hall and its staircase. Plans in 1975

to convert the school buildings to be an old persons’ club for the intended

Davenant Street Development (see below) came to nothing and demolition north

of the hall block ensued.

The Davenant Centre

Contributed by Survey of London on Aug. 24, 2017

A scheme for refurbishment of the two surviving school buildings to be a

community centre emerged from the GLC in 1984. In a project spearheaded by

George Nicholson, Chair of the Planning Committee in the GLC’s last and

defiantly radical days, more than £1m was made available for the formation of

the Davenant Centre. This ‘community resources and training centre’ was to

extend to include a new building on the empty site at 181–185 Whitechapel

Road, all to house eight local groups: the Asian Unemployed Outreach Project,

Dishari Shilpi Ghosti (musicians who had left the scene by 1988), the

Federation of Bangladeshi Youth Organisations, the Progressive Youth

Organisation, Tower Hamlets Advanced Technology Training, the Tower Hamlets

Trades Council, the Tower Hamlets Training Forum, and the Jagonari Asian

Women’s Resource Centre (see 183–185 Whitechapel Road). With the Historic

Buildings Division in close attendance, plans for the adaptation of the listed

buildings were drawn up in 1984–5 by Julian Harrap Architects with Peter

Stocker as job architect. Harry Neal Ltd carried out the building works in

1985–7, completion coming after the abolition of the GLC and despite an

attempt by Westminster City Council to stop the works. The open ground floor

under the hall was largely enclosed and the front block gained new stairs and

partitions, an upper-storey tiered lecture room being preserved. The Centre’s

Chair was Manuhar Ali and Adam Lazarus was the Development Worker. First use

was as a youth club and for computer training, welfare advice, trade-union

offices and meetings in the assembly hall. There was no reliable source of

revenue so the hall had to be advertised for hire and the Centre opened as a

music venue in 1990.

The Centre could not sustain itself and Aliur Rahman was obliged to instigate

a further conversion in 2002. Carried out in 2005–6 through ESA Architects

(Nic Sampson, job architect), Peter Brett Associates, consulting engineers,

and Killby & Gayford, contractors, this introduced much more lettable

office use, retaining space for a youth club on the west part of the front

block’s ground floor. To maximise floor space a mezzanine floor was inserted,

the loft was converted, and to the rear a glazed staircase in a ‘cylindrical

pod’ was added. The 1890s hall was also adapted for office use, the interior

retained. Despite debts and with support from Tower Hamlets Council, the

complex continued as the Davenant Centre until 2017 when in want of funding it

was obliged to close. The YMCA George Williams College took occupancy of the

front building in 2018.

St Mary Street School

Contributed by Survey of London on Aug. 24, 2017

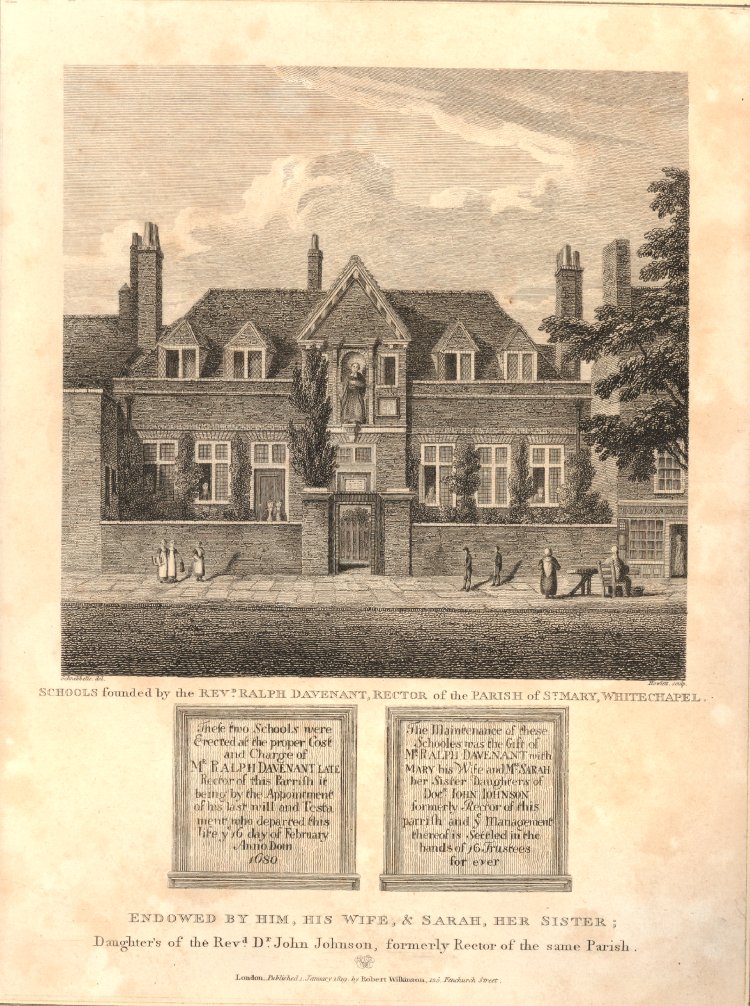

The Whitechapel Society for the Education of the Poor was formed in September

1812 as an early branch of the National Society (see above). Daniel Mathias,

Whitechapel’s Rector since 1807, headed this initiative towards educating more

of Whitechapel’s poor children. A survey of the parish had uncovered 5,161

children under the age of seven and 3,204 above that age. Of the latter, 991

attended the thirty-two schools already in the parish, leaving 2,213

uneducated. Few parents attended church, providing an additional motive for

the evangelical Society. A scheme coalesced for the establishment of a new

school with a hall large enough for 1,000 to be taught on Bell’s (National

Society) principles; it would also be used for religious service on Sundays.

The first thought was to procure an adaptable building, but by early 1813

there were plans to build on land to the north of the 1680s school and a lease

(from John Wildman) was agreed. In the event the Society decided to use this

land to extend the parish’s burial ground eastwards and to build the school on

the west part of the burial ground of the 1790s to face what had been made St

Mary Street. The Vestry gave up the land and the Bishop of London approved the

project in the summer of 1813. However, funds were wanting; despite a grant of

£300 from the National Society, the building fund was more than £1000 short of

its target of £2500. The Duke of Cambridge laid a foundation stone on 12

October 1813 in an opulent ceremony said to have been attended by thousands

that brought in £677 11 6 in donations. Completed in 1815, the building was

among the earliest purpose-built National schools. It was also, as Nikolaus

Pevsner had it in an unconscious recognition of the intended secondary use,

‘like a chapel’.

Its architect remains unknown, though for circumstantial reasons Samuel Page

is a candidate (see the entry on the rebuilding of the Davenant School). It

was a single-storey stock-brick barn of about 80ft by 120ft. Its round-headed

window openings, some very tall, had cast-iron Gothic tracery. There were

porches at both ends and a western clock turret. The main square room to the

west was for the teaching of 600 boys, with a half-sized room beyond for 400

girls, all convertible into a single space. Two rows of square timber posts

helped support a vast queen-post truss timber roof. There was a hot-air

heating system, devised and paid for by Davis with John Craven, another

Goodman’s Fields sugar-baker. Tom Flood Cutbush (the son-in-law of Luke Flood,

Treasurer to the Davenant School) procured an organ, which he played himself,

also arranging performances of oratorios in the 1820s.

In 1844–5 the Rev. William Weldon Champneys oversaw reconfiguration of the

east end, the girls’ room reduced, raised and given a railed balcony to create

space below for an infants’ school, with living rooms for the master and

mistress. Other subdivision for classrooms in the western corners followed in

1868–9 with G. H. Simmonds as architect. The west porch was lost when St Mary

Street was widened in 1881–2. George Lansbury, an alumnus around 1870,

recalled ‘what a school-building! No classrooms, one huge room with classes in

each corner and one in the middle.’ The east part of the burial ground,

disused from 1853, was taken for a playground from 1862. This was shared with

the Davenant School and a disinfecting house was inserted in its north-east

corner in 1871. The National School was also known as the Whitechapel

Society’s School, St Mary’s School or St Mary Street School. In 1874, 360

children were presented for examinations, a decade later 443. It had less

cachet than the Davenant School, which, to Lansbury, was for ‘“charity sprats”

– girls and boys dressed in ridiculous uniforms’. After administrative

changes (see below) there were adaptations in 1889–90, including the addition

of a caretaker’s house to the north. The school continued under LCC

maintenance as Davenant Elementary Schools, its roll gradually declining from

784 in 1900 to 300 in 1938. It closed in 1939. After post-war use as a second-

hand clothing warehouse and despite calls for its preservation, the building

was demolished in 1975.

The former Davenant

School at 179 Whitechapel Road in 2017 (photograph by Derek Kendall)

The former Davenant

School at 179 Whitechapel Road in 2017 (photograph by Derek Kendall)