Historical Introduction

Whitechapel is a dense and intricate palimpsest, repeatedly regenerated but with great underlying social and physical continuities. Poverty has been pervasive, often beside wealth, though more on its own in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Chaotically commercial, industrial, and productive from the medieval period to the Second World War, Whitechapel was thereafter marked by planners to remain so, but in more orderly fashion. This goal was pursued in the face of population decline and extensive bomb damage. Since 2000 wealth has returned, without much productivity, and without the departure of poverty, but bringing transformative change to the built environment.

The architecture of Whitechapel defies thumbnail characterization, except perhaps as unstandardized, at least until recently. There is much that is quotidian, vernacular even, but there is also commercial grandeur and the area has some of east London’s finest church interiors. There are many surprises, of survival, and of the innovative or eccentric. As homogenizing as a recent rash of tall buildings is in its impact, this is not the first time Whitechapel has been overshadowed by tall buildings. Numerous eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sugar refineries, all but entirely gone, stood at nine or more storeys.

Just outside the City of London astride the Great Essex Road, the main route east, Whitechapel has been a magnet for settlement for around 800 years. Immigration – principally Huguenot (French), Scandinavian, German, Irish, Jewish (Spanish–Portuguese, Dutch, and East European), Bengali, Somali, and from the rest of Britain – has been a constant since at least the sixteenth century. Whitechapel has been ‘global’ for as long as that word has denoted the world.

This is a topographical and architectural history informed by social history, which in Whitechapel is well-trodden ground. In terms of social identities, the area presents the richest and most complex of weaves, a four-dimensional tapestry. While touching on many aspects of these identities, these books do not address them directly. In part that is because history is here approached through built fabric, which is mutable as an expression of social identity, in part because the reconstruction of past mentalities, whether possible or not, is a different endeavour.

Whitechapel is certainly a place of transience and of sometimes short-lived traditions about which the word ‘community’ has often been misleadingly used, obscuring agency, the lack of it, and syncretic forces. The area’s brutalities and obsolescences always enjoin ‘follow the money’. In contemplating Whitechapel’s interwoven historic identities, many of which are now residual, and often concealed contributions to the history of the place, Stuart Hall’s words resonate – ‘I am the sugar at the bottom of the English cup of tea.’[1]

Some definitions are required. The parish of Whitechapel was once larger, extending south to the Thames. Those southern parts, known as Wapping–Whitechapel and separated off since 1694, are not covered here, nor are lands west of Mansell Street now in the City of London but formerly in Whitechapel, including the site of Holy Trinity Minories, part of the Liberties of the Tower of London that was united with Whitechapel in 1895. The parish boundary to the south of Whitechapel Road, which slices through the London Hospital estate bisecting buildings, is treated here as porous and similar small rationalizations are made elsewhere.

ROMAN WHITECHAPEL

Roman London was surrounded by a cemetery, or rather several cemeteries. Roman law prohibited burial within the City – hominem mortuum in urbe ne sepelito neve urito; the dead were typically buried just outside, beside roads. Immediately beyond the City to its east and with a road through it, the land that later became Whitechapel was thus a likely locus for Roman burials. A cemetery, commonly known as the Eastern Cemetery, inferred from archaeological finds from the late seventeenth century onwards, seems to have covered most of western Whitechapel. Sherds of Bronze Age pottery and worked flint suggest only minimal pre-Roman activity. Further findings indicate a major Roman road running eastwards from Aldgate, possibly with an earlier more southerly route, and another road skirting Whitechapel’s southern edge, beyond which lay marshes. Numerous groups of burials have been found near these roads. The City expanded considerably from its first century core, but its limit was marked by a great wall erected around 190 to 220 CE. East of the towered gateway at Aldgate, the only evidence of activity found in Whitechapel, apart from the roads and the cemetery, are traces of field boundaries and quarrying for brick earth and gravel of uncertain date but predating the burials. While pottery has been found at Green Dragon Yard, there is no evidence of Roman settlement in Whitechapel. Lands beyond the cemetery might have been cultivated as market gardens.[2]

To examine this more closely and to start with the roads, it is known that a road from Londinium to Camulodunum (Colchester), the earlier capital, was constructed in the late first century CE running eastwards from Aldgate and crossing the River Lea at Old Ford. Its line is still, and perhaps always will be, a matter for debate, but it seems to have established the line of Aldgate High Street (where Roman gravel metalling was discovered in 1938), and Whitechapel High Street. It then either continued to run straight on a slightly more northerly line than that of Whitechapel Road, or swung slightly northwards around the current Whitechapel Station. The realignment southwards to Whitechapel Road probably came later, in early medieval times, possibly instigated by Queen Matilda in the early twelfth century.[3]

An even earlier road to Colchester, probably built not long after the establishment of Londinium in the mid first century CE, has been inferred as running from around Haydon Street through the vicinity of Alie Street towards the Old Ford crossing, explaining Roman burials much further south than the Aldgate–Whitechapel line. A further minor road evidently skirted the southern edge of Whitechapel along the line of the Highway with burials alongside. A cemetery access road ran south-east from the Minories to Hooper Square.[4]

The exact limits of the Eastern Cemetery are unknown. Finds indicate cemetery use across a wide area between the Minories and Back Church Lane. In 1720 John Strype recorded: ‘In Goodman’s Fields, without Aldgate, was a Roman Burying Place. For, since the Buildings there, about 1678, have been found there (in digging for Foundations) vast Quantities of Urns and other Roman Utensils, as Knives Combs, &c. … Some of these Urns had Ashes of Bones of the Dead in them, and Brass and Silver Money: And an unusual Urn of Copper, curiously enamelled in Colours, Red, Blue, and Yellow.’[5]

The significance of these objects was confirmed in the late eighteenth century, when finds were more routinely recorded. A minimum eastern limit to the cemetery was established in 1776 with the discovery of a tablet, now lost, to Julius Valens of the Twentieth Valerian Victorious Legion, probably of the late first century, on the east (Stepney) side of Back Church Lane. A small grave slab, probably of the early third century, commemorating Flavius Agricola, a private in the Sixth Victorious Legion, and erected, so the stone records, by his wife Albia Faustina, was found in 1787 in the former tenter ground on Goodman’s Fields. Roman funerary urns were found below Whitechapel High Street opposite Leman Street in 1836.[6]

Extensive excavations in the 1980s filled out the picture of the Eastern Cemetery, and suggested a possible northern limit parallel to and north of Alie Street.[7]

The archaeological evidence indicates that the cemetery was in use from the beginning of the second century to the early fifth century and that it was at least twelve hectares (thirty acres) in extent. More than 570 burials and a hundred cremations have been identified, with ashes placed in pots, amphorae, lead urns, tile cists, stone containers, and wooden casks. There were pits in which cremations took place, along with pig and chicken bones suggesting funerary feasting. Cremations were more typical of the earlier period, burials generally later, though examples of both from all periods have been identified. Recent analysis of an adult male skeleton found near Mansell Street has indicated African ancestry. Remains of funeral pyres, unique in a Roman London cemetery, indicate on-site cremation. Masonry and timber fragments are believed to be remnants of mausolea and other funerary structures. Grave goods including glass vessels of the second and third centuries have been found. Concentrations, as around the former tenter ground and Hooper Street, where there was an extensive cemetery within a ditched enclosure, suggest the clustering of graves by family association or religious practice within the larger area of the Eastern Cemetery, which may more properly be seen as a collection of cemeteries.[8]

MEDIEVAL WHITECHAPEL

Then, for close to a millennium, the record is silent. It seems that human activity in Whitechapel was passing and agricultural. The manor of Stepney, encompassing Whitechapel, was part of a larger landholding held by the bishops of London since before 1000, probably from around 604; it was their principal estate. Whitechapel was an independent parish from some time shortly before 1320, the first ‘hamlet’ in the vicinity of the Tower of London to separate from the vast mother parish of St Dunstan, Stepney. Its mid thirteenth-century chapel, dedicated to St Mary ‘de Matefelun’ (later Matfelon), named the parish. The first recorded use of the name ‘white chapel’ is from 1344 when a toll was levied on carts passing between the chapel (by then the parish church) and Aldgate. Originally around 211 acres (eight-five hectares), the parish included territory south to the Thames that later became the parish of St John, Wapping, which separated in 1694. Boundaries seemingly followed those of fields or estates, except perhaps along Back Church Lane, which was part of a meandering medieval route linking Whitechapel’s parish church and the then essentially unpopulated riverside parts. The otherwise north–south City-side parish extended eastwards along the realigned main road up to but excluding high-status houses at Mile End Green.[9]

This road remained the main route in and out of London to points east. Its margins were probably open waste, but it is likely that the inner or High Street section was lined with buildings by the thirteenth century when the chapel was built beyond its east end. As Algatestreet the future High Street accommodated numerous shops by the fourteenth century, doubtless including at least some of twenty-four in Whitechapel sold in 1365 by John Chaucer, a vintner and the father of the poet. Inns or taverns on the High Street by the 1450s included the Hammer, the Swan, the Cock, and the Hart’s Horn, those just the firmly documented; there were surely many others.

The Franciscan abbey of St Clare without Aldgate was founded in or by 1293 just outside the parish to the west. Its nuns, Poor Clares or Minoresses, gave their name to the Minories. After the Reformation their chapel became a parish church, Holy Trinity Minories. The site was in part later that of Haydon’s Yard. Fields to the east of the abbey, up to fifty acres later known as Homefield, were a major part of lands held from the bishops of London by the Trentemars family from the twelfth century, with a large house on the east side of the Minories south of the abbey, called Bernes in 1395 when John Cornwaleys inherited an interest. He subsequently consolidated control of the manor of Bernes (or Barnes) and also had copyhold tenure of other property north of Whitechapel Road. Homefield is said to have been used by the Minoresses as a convent garden or farm, that is market garden. Further south was the Cistercian abbey of St Mary Graces, founded in 1350 on the site that later became that of the Royal Mint, also outside the parish of Whitechapel, but with lands within it that extended east to the site of Wellclose Square.

Eight acres in the north-west corner of the parish, an estate known as Woodlands by the sixteenth century, were part of the Trentemars estate and pertained to the priory of St Mary Spital before the Reformation. Land to the east of that was also part of the Trentemars, then Bernes or Cornwaleys, estate up to the fifteenth century, in fragmented ownership thereafter. A smaller holding north of Whitechapel Road to the east of present-day Osborn Street descended by marriage to John Bramston in the late fifteenth century.

Ashwyes ‘Great Field’, seventy-five acres in the late thirteenth century, lay to the east on the south side of Whitechapel Road, much of it outside the parish, with a manor house by 1324 on the eastern parish boundary at Mile End Green, which place name also applied in this period to large expanses of manorial waste on either side of the road. These wide verges east of the church were gradually built upon from the late sixteenth century. The main road aside, communications were poor across the open land, and the river Thames had little direct relevance to the life and economy of the parish in the medieval period, the part separated in 1694 excepted.

LAND TENURE AND DEVELOPMENT, 1550 to 1800

The manor of Stepney continued to be a primary landed interest across Whitechapel, especially in northern parts of the parish, and beyond. In 1550 and by prior agreement, Nicholas Ridley, the then newly installed Bishop of London, surrendered Stepney manor to King Edward VI, who at once granted it to the Lord Chamberlain, Sir Thomas Wentworth (1501–1551). Thomas Wentworth (1525–1584) inherited and his son Henry Wentworth (1558–1593) followed as, in due course, did his son, another Thomas Wentworth (1591–1667), created earl of Cleveland in 1626. A courtier, Cleveland ran up debts and mortgaged the manor in 1632 by a ninety-nine-year lease. He could not clear his debts and creditors took possession of the manor and held its courts from 1641. Cleveland was a royalist whose estates were sequestered in 1650; he was a prisoner in the Tower from 1651 to 1656. After the Restoration in 1660 he obtained Private Acts of Parliament to permit him to sell land to pay debts, having settled a lease to trustees in 1658 of properties that included Stepney manor, now much diminished by the sale of free and copyhold lands, to provide an income for Philadelphia, Lady Wentworth (d. 1696), the wife then widow of his son Thomas (c.1613–1665), Lord Wentworth. She sold the manor, still mortgaged, in 1695, when it was described as comprising 200 acres of pasture, four messuages, and twenty cottages, to trustees for William Herbert, Lord Montgomery. The manor passed via further sales to Windsor Sandys in 1710, John Wicker the younger in 1720, and (Sir) George Colebrooke in 1754. There was a flurry of enfranchisements in Whitechapel and beyond in 1772. Colebrooke’s descendants held remnants of Stepney manor down to Sir Edward Arthur Colebrooke (d. 1939), remaining copyholds having been converted to freeholds in 1926.

Consequential changes in manorial land tenure occurred in the early seventeenth century. The prodigious outward growth of London into its suburbs had increased property values and from 1584 disputes arose between the then lord of the manor, Henry, the third Lord Wentworth, and his tenants. In spite of growing pressure to switch to a leasehold pattern of landholding, Wentworth resisted administrative and legal changes, leading to ever more complicated fragmentation of leases and confusion over responsibilities for maintenance. Arbitrary fines and the imposition of restrictions on sub-letting angered tenants. A manorial debtors’ prison on the north side of the waste (at present-day Court Street) cannot have helped. While long-term investment in land tended to be discouraged, long leases could be secured – a 500-year lease of a large chunk of waste on the south side of Whitechapel Road (the sites of Nos 100–146) was granted in 1584–5.

Wentworth’s general approach to land tenure was increasingly incompatible with the area’s rising economic forces and it tended to impede development. Concessions were granted in 1587 in exchange for £3,000 from the tenants, but the peace did not last under the young and spendthrift fourth Lord Wentworth, the future Earl of Cleveland. He obtained a patent in 1615 to allow him to offer virtual freeholds to his tenants. Negotiations followed, copyholders led by City merchants mounting a co-ordinated challenge against seigneurial inflexibility. For another £3,500 the tenants secured a Chancery decree in 1617 that formalized new ‘Customs’, including a right of unlicensed subletting for terms of up to thirty-one years and four months, and a right to enfranchisement, copyholders henceforth being free to re-assign their leases at their own discretion in perpetuity, subject to customary renewal periods of up to thirty-one years, renewable and increasingly a formality. There was a confirmatory Act of Parliament in 1623.

This agreement brought greater stability. But after Cleveland’s death in 1667, the manor was so encumbered with debt and troublesome to manage that Philadelphia, Lady Wentworth, enabled by the patent of 1615, sold off property where she could, enfranchising copyholds as freeholds, and permitted more building on wastes. She granted more 500-year leases, several in 1670 and 1672 of waste property on the north side of Whitechapel Road, in and behind the present Nos 197–317. Elsewhere, the thirty-one year customary limit to sub-leases was not a constraint on development, nor is it an explanation for a perceived dominance of piecemeal building, as has sometimes been argued. Longer leases, most frequently of sixty-one years, were widespread after 1680, even where copyhold nominally endured on a much-diminished manor.[10]

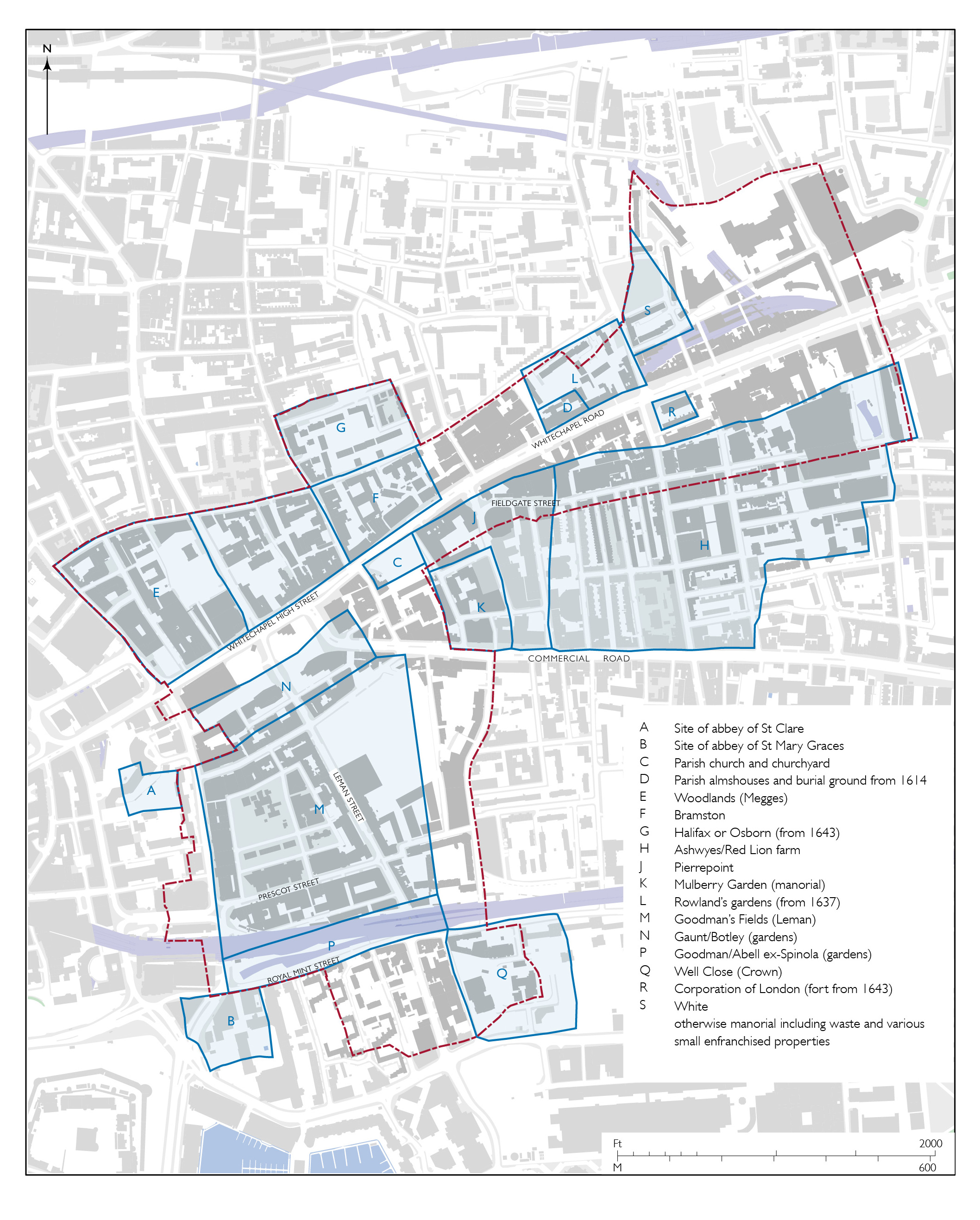

Map of Whitechapel’s main landholdings in the early seventeenth century (drawing by Helen Jones)

Other secular landowners had long established holdings in Whitechapel, as on the Ashwyes and Barnes estates. After the Reformation these and other holdings were consolidated. Sixteenth-century settlement and mercantile wealth was in large measure a function of the proximity of the City, conditioned in part by roadside trade and industry, as well as by access to the Thames. William Megges, a merchant, acquired the Woodlands estate in 1577, won legal victories regarding sub-leases in 1587–91, built a mansion (the Harte’s Horne) and purchased the freehold in 1596. The Barnes lands became Goodman’s Fields after the family that held a lease from the 1530s and the manor from 1594, generally maintaining farm use of open fields. Benedict Spinola, a Genoese merchant, took the eight most southerly of the Goodman acres north of what is now Royal Mint Street in the 1570s and laid out twenty garden plots for tenter yards and garden houses. Horatio Franchiotto, a merchant from Lucca, and Sir James Deane built a great house across five of these plots on fifty-year leases of 1597–8.

Considering Whitechapel in 1603, John Stow famously described building on the manorial waste along the ‘large street’ (Whitechapel High Street and Whitechapel Road): ‘both the sides of the streete bee pestered with Cottages, and Allies, even up to White chappel church: and almost halfe a mile beyond it, into the common field: all which ought to lye open & free for all men. But this common field, I say, being sometime the beauty of this City on that part, is so incroched upon by building of filthy Cottages, and with other purprestures, inclosures and Laystalles (notwithstanding all proclaimations and Acts of Parliament made to the contrary) that in some places it scarce remaineth a sufficient high way for the meeting of Carriages and droves of Cattell, much lesse is there any faire, pleasant or wholsome way for people to walke on foot: which is no small blemish to so famous a city, to have so unsavery and unseemly an entry or passage thereunto.’[11] This need not be understood as precisely accurate. Stow and others saw Whitechapel and London’s other suburbs as ruined by growth, as disorderly places where building needed to be controlled if not prevented. Elsewhere, Stow reported that Whitechapel possessed ‘fair hedgerows of elm trees’, numerous garden houses, tenter yards, and bowling alleys.[12]

Whitechapel parish Vestry enclosed part of the waste on the north side of Whitechapel Road in 1614 for almshouses and a burial ground, overflow from the parish churchyard. Around this time several mulberry gardens were planted on the margins of the parish, possibly in connection with the already established local silk industry, principally in Spitalfields – Mulberry Street is a reminder. In 1616 the Bramston estate’s copyhold was enfranchised, as was that of the Swan brewery, large premises on the west side of what became Osborn Street. Thomas Pierrepoint took several acres immediately east of the parish church and south of Whitechapel Road by 1620, from manorial waste and from the Ashwyes holding, which was known as Red Lion Farm by the end of the seventeenth century. By 1633 Edmund White, a Puritan merchant adventurer and founder of the Massachusetts Bay Company, held a freehold estate of twenty-four acres, part of which was in Whitechapel to the north-east.

Wentworth Street and Old Montague Street were laid out around 1640, around when ‘great’ gardens were established on either side of Old Montague Street: to the south by William Rowland, a market gardener who gradually built up copyhold and then freehold possession of several acres, building some roadside houses in the 1640s; and to the north by Leonard Gurle, a nurseryman, whose tenanted grounds included most of the rectangular part of the parish, about seven acres, that lay north of the Bramston land. Edward Montagu and others acquired ownership of this with other land in Spitalfields in 1643. Through inheritance, by George Montagu, Baron Halifax, and by Sir George Osborn, this became the Halifax or Osborn estate. Also in 1643, the Corporation of London built a fort on the south side of Whitechapel Road, part of a defensive ring constructed against the possibility of Royalist attack. The fort was used as a rubbish dump after the Great Fire and came to be known as Whitechapel Mount.

In 1673, Philadelphia, Lady Wentworth, applied to the Crown for a licence for a scheme for building on the wastes on both sides of the road between the disused fort and Stepney Green to the east, frontages that were in fact already much built up. Christopher Wren, as Surveyor-General of the King’s Works, prepared a survey plan and a licence was granted, but nothing followed. All along Whitechapel Road copyhold and freehold were intermixed. On the land north-east of Rowland’s, a younger Edmund White saw to the building of streets and houses in the 1670s and ’80s, including White’s Row (the west end of the present Durward Street), issuing unusually long 110-year leases. An acre was left open as a Quaker burial ground, established in 1687. A 500-year manorial lease of land at Court Street was granted as late as 1703.[13]

Parts of the parish around the High Street and the west end of Whitechapel Road were densely built up by 1680, with a network of alleys running through to Wentworth Street and Old Montague Street, intensifying the kind of development that Stow had considered problematic. The formation of Goulston Square around 1690 introduced a touch of regularity. To the south, the area west of Well Close was comparably densely built, and even more irregular and low-grade.

Giles Kinchin had taken a former mulberry garden south-east of Whitechapel’s parish church for market gardening in 1679, by when Matthew Penn was running another commercial garden on the south side of Whitechapel High Street. John Skinner, an apothecary, established a Physick Garden around 1692 off Back Church Lane.

Christopher Clarke, a Warden of the Drapers’ Company, acquired a frontage to Whitechapel Road west of the parish almshouses (the site of Nos 131–145) in 1659, leaving it to the Drapers’ Company when he died in 1672. John Venner bought an adjacent six-acre copyhold estate between the Bramston and Rowland holdings in 1693–4.

London’s suburban growth was inexorable and Whitechapel was not spared. The 1680s were a key decade for the march of bricks and mortar through Whitechapel in a fusillade of planned speculative developments. Goodman’s Fields had been sold to Sir John Leman in 1628, whose grandson, Sir William Leman, inherited in 1667. He oversaw the laying out of a grid of roads from 1678 and from 1682 granted leases of large parcels of land to several developers, including John Hooper and John Bankes, both timber merchants. To ensure good-quality work to a ‘Scheme’, most of the details of which remain unknown, it was explicit that the leases had to be long (sixty-one years or thereabouts), with the houses of brick and following the specifications of the Act of 1667 for rebuilding the City. Even so, the process saw numerous corruptions and disruptions, not least on Prescot Street in the late 1680s where Sir Thomas Chambers, the head lessee, manipulated William Chapman, a ‘master builder’, into penury. Most of the Leman frontages were built up by the 1690s, many with houses of prestigious amplitude, though gaps persisted into the eighteenth century. To the north gardens on land that had been held by Edward Gaunt then Anthony Botley were acquired around 1681 by Thomas Neale with a view to laying out more streets and houses. Neale sold up to Edward Buckley, a brewer, whose son of the same name oversaw development of a tighter grid from 1683, granting leases of up to seventy-nine years. To the south-east, Nicholas Barbon and partners purchased Well Close from the Crown in 1682, with a view to development that was primarily a means of supporting an innovative fire-insurance project. (Sir) John Parsons, another wealthy brewer, joined Barbon and others in seeing to the laying out of Marine (later Wellclose) Square. Its original name reflected the growing influence of maritime people and pursuits on this part of the as yet undivided parish – not just mariners, including many captains, but also the riparian timber trade, in large measure of Scandinavian origin. Early leases from Barbon’s consortium were most commonly for sixty-one years, but development faltered and 999-year leases were issued in the 1690s to try to stimulate building in this marginal location.

The variability of lease lengths across these projects indicates the unsettled nature of leasehold development; systems and standards were not yet established. It is clear beyond doubt that observation of the 1617 ‘custom’ of thirty-one-year lease limits had fallen by the wayside.

In the eighteenth century sixty-one-year leases were the most common type, for example on the Drapers’ Company estate in 1717 and 1759, and on what had become the Baynes (formerly Pierrepoint) copyhold estate on the other side of Whitechapel Road where concerted development began in 1764. Anthony Forman enfranchised this property in 1770.

Further east on the south side of Whitechapel Road, the London Hospital had acquired a roadside site in 1750, chosen for its openness. The hospital acquired extensive lands to the south that had been the Red Lion Farm estate in 1755 and 1772, the New Road having been cut through in 1754–6, connecting the institution to riverside districts. Planned development of the London Hospital estate on sixty-one-year leases began to the west in 1787, modest houses rising up on an array of closely spaced streets. Building closer to the hospital on the east side of New Road was not countenanced until after 1800 when the Corporation of London redeveloped the site of Whitechapel Mount. The streets that followed were more generously spaced.

The importance of the timber trade to development in Whitechapel has been noted. From the 1680s housebuilding was mainly in brick, but timber houses did continue to go up well into the eighteenth century, as on Wellclose Square. As was common, many of the area’s leading builders were carpenters, ranging from William Ogbourne, who lived on Chamber Street and took over a Board of Ordnance wagon yard of the 1680s to its south for his timber yard, to Samuel Hawkins, who gained a local foothold through secondary development on Goodman’s Fields in the eighteenth century, and whose sons and later descendants retained possession of property there into the twentieth century. Joel Johnson, another eighteenth-century carpenter who had a yard to the west of Back Church Lane, came to style himself an architect and was responsible for designing chapels and working on the London Hospital where he was succeeded by his partner, Thomas Langley.

Of course, not all builders were carpenters. Samuel Ireland, a Spitalfields bricklayer, put up the four shophouses at 261–267 Whitechapel Road in 1767–72 with Woods Buildings, a court of eighteen smaller houses to the rear. Thomas Barnes (d. 1818) was the first bricklayer to establish himself as a substantial builder in Whitechapel. From work for the London Hospital in the 1770s he moved on to undertake quantities of speculative houses on the hospital’s estate from 1788, including on New Road, where some of his houses still stand. His lower-quality development north of present-day Durward Street from 1796 has gone, as have courts of instant slums he built to the north of Whitechapel High Street soon after 1800.

POPULATION AND SOCIAL CHARACTER

Whitechapel’s population would have numbered in the hundreds before the sixteenth century. The parish church had 670 communicants in 1548, almost as many as the larger western suburban parish of St Martin in the Fields. This suggests a total population of rather more than 1,000. Greater precision is not possible.[14]

Thereafter population boomed, generating the disorder bemoaned by Stow. London’s population as a whole doubled in the first half of the seventeenth century, and it seems clear that this was proportionally surpassed in Whitechapel. The growth had been so prodigious that around 3,000 people died in Whitechapel in the plague year of 1625, suggesting a population at least double that. Four years later Whitechapel was among a ring of parishes added to the Bills of Mortality, through which plague deaths were monitored. In 1665 the parish registered 3,855 burials. A year earlier there were 2,482 households in Whitechapel excluding Wapping, indicating a total population somewhat greater than 10,000. Another half-century on, the population of Whitechapel in 1710–11 has been estimated at 18,000. As devastating as outbreaks of plague had been, mortality in London’s eastern suburbs in the eighteenth century was not as high as in places further west and north, from Shoreditch across to St Giles. Compared to what had gone before there was relative stability.[15]

That did not last. Estimates of the population of Whitechapel rise from 23,666 in 1801 to 64,141 in the late 1830s, dramatic growth even by the standards of early nineteenth-century London. It continued up to about 1851 to a measured peak of 79,959, with a density of 220 persons per acre (544 per hectare). St Mark’s parish covering Goodman’s Fields had a population of 15,790 in 1851 in only 1,757 households. Its average of about nine people per household was the highest in east London.

Decennial census figures for Whitechapel’s population from 1861 to 1881 (78,970 to 76,046 to 71,363) indicate a slight decline. Numerical stabilization followed up until the First World War, but overcrowding in Whitechapel was still worse than anywhere else in London in 1902. Density had declined to 195 persons per acre in 1866 (when the corresponding number for London as a whole was 39), then to about 140 in 1921. The Common Lodging Houses Acts of 1851 and 1853, which prescribed densities, might have been one factor, others were emigration, movement further east to be closer to dock labour, and decline in the sugar industry and more widely from 1864–6. Whitechapel saw a net loss of population through migration in every decade between 1851 and 1901 except the 1880s, when the net gain was just ninety-seven people.[16]

Comparable figures for Whitechapel alone for most of the twentieth century are not readily obtainable. Across Tower Hamlets, and it is clear this applied to Whitechapel, there was dramatic population decline, from 597,000 in 1901 to 142,841 in 1981.[17]

Immigration

Migration into Whitechapel from other parts of Britain has been more or less a constant in line with overall population trends, as it has for other parts of London, and is here taken as read. What is more distinctive about Whitechapel is immigration from overseas. Since at least the sixteenth century, this has been a major factor in the shaping of the area’s built environment, perhaps more so than in any other London district.

In 1523 a statute ordained that all ‘aliens’ using handicrafts in suburbs including Whitechapel should be controlled from the City.

An attempt at quantification identified 169 foreigners in Whitechapel in 1571. Only in Shoreditch and East Smithfield among suburban districts were there more. Benedict Spinola and Horatio Franchiotto, wealthy Italian merchants, have already been mentioned as late sixteenth-century property developers in the part of Whitechapel adjoining East Smithfield.[18]

Mercantile connections in the City and the port were one motivation for immigration, others were opportunities for skilled tradesmen, and freedom from religious persecution. Johannes Banfi Huniades (János Bánfi-Hunyadi, 1576–1646), the Hungarian son of a Calvinist bishop, and a goldsmith, chemist and alchemist, was living in Whitechapel in 1625. The majority of those identified as ‘strangers’ in Whitechapel in 1635 were weavers.[19] Many of these would have been French Huguenot silk weavers, though the main centre of London’s silk industry and of Huguenot immigration after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 was to the north in Spitalfields. More than weaving, the northern parts of seventeenth-century Whitechapel accommodated silk throwing. The Rev. Richard Welton, Whitechapel’s non-juring rector from 1697 to 1715, spurned the area’s Huguenot immigrants: ‘This set of rabble are the very offal of the earth, who cannot be content to be safe here from that justice and beggary from which they fled, and to be fattened on what belongs to the poor of our own land to grow rich at our expense, but must needs rob us of our religion too.’[20] G. Reginald Balleine quoted this in 1898 with the comment, ‘how blind this prejudice was … May we learn the obvious lesson for ourselves!’[21]

London’s Danish–Norwegian Lutheran population, maritime–mercantile and mercenary through the timber trade and soldiering, gained a focus on Wellclose Square with the building of a church there in 1694–6. This group was comparatively small in numerical terms, certainly in relation to eighteenth-century German immigration, mainly from northern Hanover between Bremen and Hamburg. This was essentially due to the rapid growth of the sugar-refining industry in Whitechapel. Early eighteenth-century German immigrant entrepreneurs established sugarhouses and brought skilled male workforces in their wake. Religion was, as ever, paramount in cultural continuity for immigrants. The German Lutheran Church of St George on Alie Street, which opened in 1763, was a reflection of and a statement by this population. Whitechapel’s Germans were reinforced around 1800 by a wartime influx of sugar entrepreneurs with skilled and unskilled workers. Further German churches opened in Whitechapel in 1819 and 1861 and schools were established alongside. East London’s Deutsche Kolonie came to number in the thousands and London’s German population as a whole rose from 16,082 in 1861 to 27,290 in 1911. Whitechapel and adjoining districts remained a focus for settlement, in part because most immigrants arrived in the docks. Whitechapel’s German population shifted gradually from dependence on sugar baking, which declined from the 1860s, to a range of other and more standard trades, becoming known for its publicans, butchers, bakers, and domestic servants. There was some migration out of Whitechapel beforehand, but it was the First World War that caused the demise of the Deutsche Kolonie. Enormous anti-German sentiment in 1915 after the sinking of the Lusitania and the first Zeppelin raids led to deportations and internments for those who had not anyway departed. There was a limited revival, and Whitechapel sustained two German congregations throughout the twentieth century.[22]

Among the poorest of Whitechapel’s immigrant groups were the Irish, who were present in numbers by the early eighteenth century, principally as street-sellers and dock-labourers, and concentrated around Rosemary Lane (Royal Mint Street) and Saltpetre Bank (Dock Street). It has been estimated that there were over 23,000 Irish in all London by the 1780s. The south end of Leman Street witnessed anti-Irish riots in 1736, prompted by fears of lost work on account of cheap labour. The Catholic Irish clashed with Methodists in 1806 and there were Irish-led riots against German workers in 1853, the Irish this time reacting against cheap labour. Following famine in Ireland in the 1840s, immigration peaked in the 1860s. From 1851 to 1881 a steady 64–65 per cent of Whitechapel’s population was London-born. In 1881 twenty-one per cent were born in the British Isles outside London, of which twenty-two per cent were Irish – that is, just under five per cent of the total population. Southern parts of the parish of Whitechapel maintained a strong Irish-Catholic identity throughout the twentieth century.[23]

Jewish immigration is both the most complex and the best-documented element of Whitechapel’s demographic history. Following on from the Resettlement of 1656 it has Iberian beginnings, with Sephardic immigration from Portugal at the beginning of the eighteenth century stimulated by the Anglo-Portuguese treaties of 1703 and the need to escape the Inquisition. Sephardim, Spanish and Portuguese, sometimes coming to London via Holland or Hamburg, initially settled on the eastern margins of the City. Unlike in other European cities there was no ghetto system in London, but Jews were barred from owning land or property freehold within the City, not because they were Jews, but because they were classified as ‘aliens’. Thus, Jewish merchants, bankers, and traders tended to establish residence as close to the commercial centre as possible on the edge of the City. Bourgeois Sephardic Jewish settlement gradually radiated eastwards from Aldgate to the newly formed streets and the mostly large houses and mansions of Goodman’s Fields, which were used as places of business as much as homes. It was reinforced after 1720, mainly by Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi immigrants, many from Germany and Amsterdam, most notably the Goldsmid family of financiers who resided on Leman Street. Some of the immigrant merchants had links to Brazil and other colonies through Portuguese or Dutch connections, and there were involvements in the diamond and Caribbean trades. But Jewish settlement in Whitechapel was always at both ends of the social spectrum. The Jewish poor were a strong presence in eighteenth-century Whitechapel, stereotypically Ashkenazi though of less determinable origins, especially in the shape of itinerant ‘old clothes’ sellers on Petticoat Lane and Rosemary Lane (Rag Fair), among whom vagrancy and criminality were reportedly common. Initially poor, subsequently wealthy, Samuel Falk (the Ba’al Shem) was exceptional, a Galician immigrant who came to London via Bavaria and Amsterdam to live humbly on Prescot Street then more opulently on Wellclose Square from the 1740s to the 1780s. England’s total Jewish population rose in the course of the eighteenth century from under 5,000 to around 10,000, nearly all in London. Wealthier Sephardim began moving away around 1800. Goodman’s Fields was in 1823 explicitly deemed ‘no longer sufficiently select’.[24]

Eastern European Ashkenazim continued to enter Britain during the nineteenth century and settlement spread along the Whitechapel Road and Commercial Road and into their hinterlands. Whitechapel was already called ‘the Jews’ quarter’ in 1862, but a year earlier Henry Mayhew’s collaborator, Bracebridge Hemyng, had explained that ‘Whitechapel has always been looked upon as a suspicious, unhealthy locality. To begin, its population is a strange amalgam of Jews, English, French, German and other antagonistic elements that must clash and jar, but not to such an extent as has been surmised and reported.’[25] The establishment of several synagogues in the 1870s, and a report in 1878 that poor Jewish immigrants from Poland exacerbated overcrowding illustrate continuing growth in Jewish settlement.[26]

The assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881 unleashed waves of pogroms against Russia’s Jewish subjects. This was the catalyst for the largest ever influx into Britain of Jewish refugees, an estimated 100,000 between 1881 and 1914. The majority were from the gigantic ghetto known as the Pale of Settlement, along the western borders of the Russian Empire from the Baltic to the Black Sea. This immigration changed the face of Britain’s Jewish community, making Ashkenazim the dominant group by far, some eighty per cent of British Jewry. Booth recorded 28,790 Jewish people in Whitechapel in 1887.[27]

Given pre-existing Jewish settlement and proximity to the port, east London was the point of arrival for the majority of Jewish immigrants. By the end of the nineteenth century, ‘Jewish East London’ was one contiguous neighbourhood that ranged from Spitalfields in the west, through Whitechapel, to Stepney and Mile End in the east. The Jewish presence was sparser east of New Road, and south of Cable Street.

Late nineteenth-century immigrants from eastern Europe, ‘Russians’ as they were often known, did not mix much with the area’s earlier Jewish population. Samuel Montagu, who led efforts to support and assimilate the new arrivals, not least through synagogue building, offered £100 to help catch Jack the Ripper because the murders led to an upsurge in antisemitic attacks and rhetoric. Arnold White’s The Destitute Alien in Great Britain (1892) linked Jews, poverty, and crime, and stirred up hatreds that led to the Aliens Act of 1905 restricting immigration. The King Edward VII Memorial Drinking Fountain on Whitechapel Waste, erected in 1911 from subscriptions raised by east London’s Jewish inhabitants, was a direct response to open and aggressive antisemitism.

The Jewish presence rooted itself in a myriad of ways, including through manufacturing, particularly clothing (the rag trade), markets, synagogues, schools, clubs, and theatres. Yiddish was widespread, not least in Hebrew script on shop fascias and windows. The Battle of Cable Street on 9 October 1936 was a moment of great significance when local Jews, with Irish Catholics joining in solidarity, repelled a march by the British Union of Fascists led by Oswald Mosley. Gardiner’s Corner was a flashpoint, as was Cable Street’s junction with Dock Street, where the event is commemorated by a plaque on Nos 3–5. Vaytshepl, Mayn Vaytshepl, a sentimental song written by Chaim Tauber around 1940, encapsulates attachment to the place. Bombing and evacuations fed an exodus to the suburbs, already discernible well before the war. This became irreversible and was largely complete by the 1960s. Since the 1980s much of the fabric of the ‘Jewish East End’ has been erased.[28]

South Asian sailors were a presence in east London, travelling to and fro, from the early days of the East India Company in the seventeenth century. Asian seamen, often called lascars (deriving from Arabic ranging to Urdu words for ‘soldier’), were by the end of the eighteenth century accommodated in lodging houses in Shadwell. The Strangers’ Home in Limehouse opened in 1857 and lodged thousands.

From 1805 enclosed docks lay just a stone’s throw south of Whitechapel. The presence in the area of sailors of diverse origins was somewhat regularized by the establishment in the 1830s of the Sailors’ Home east of Dock Street. A transient population grew and in other respects the vicinity became an established centre for seamen. By the 1930s Maltese, Cypriot, Caribbean, Bengali, Pakistani, and Somali sailors were settling in the area around the west end of Cable Street. Many Bengali lascars came from Sylhet, a north-eastern district of East Pakistan from 1947 to 1971. Sylheti immigration to east London increased and Stepney Borough’s documented south Asian population, mostly single men, grew from 680 in 1951 to 1,605 in 1961. Slum clearances around that time in the Cable Street area pushed this population north into Whitechapel and Spitalfields. This was the only time that a major immigrant population in Whitechapel originated from maritime trade, from sailors. More Sylhetis arrived in the 1960s, also Punjabis and others from West Pakistan, including Sikhs. Asian-run shops opened on Black Lion Yard and Old Montague Street, others around Middlesex Street. Brick Lane was a centre for work in the clothing industry, especially tailoring.

By 1970 racist violence against this population had become a stark and growing problem. Many people abused as ‘Pakis’ were Bengalis from what became Bangladesh in the Liberation War of 1971. Documented attacks in 1977 numbered in the hundreds; many others went unreported. Matters came to a head in May to July 1978, following the murder of Altab Ali. This was a turning point when resistance was mobilized, mainly by young people. The success of unity against the National Front and other racists in 1978 has been compared in its significance to the Battle of Cable Street forty-two years earlier.[29]

Many single male Asian immigrants had nurtured notions of return. But these dissipated, and from the 1970s wives and children arrived to join husbands. Violence did not vanish entirely, but roots strengthened. For this very largely Muslim population, a notable anchor in Whitechapel was the East London Mosque, present from 1975. Other aspects of impact on the built environment are detailed below. The census of 2001 identified around fifty-two per cent of the population in Whitechapel Ward as ‘Bangladeshi’. Across Tower Hamlets this proportion remained stable in 2011 when forty-nine per cent of the total population identified as Muslim. Since then east London’s Bengali population has been reinforced by immigration from Italy, onward movement of people including many skilled graduates from Dhaka, Bangladesh’s capital.[30]

Poverty and its representations

Stow’s ‘filthy Cottages’ implies poverty in Whitechapel by 1600, and accounts of Rag Fair, the second-hand clothes market on Rosemary Lane, make it manifestly clear without digging deep that the poor were widespread in early-modern Whitechapel. The conversion of stabling at the Red Lion inn on the High Street’s south side to tenements for poor people shortly before 1616 seems indicative of increase. That this is known is due solely to concerns that more poor, in particular orphans, meant an increased burden on parish funds.

Among the more architectural and otherwise historically visible aspects of the presence of the poor were almshouses, which appeared from the early seventeenth century in what became a concentrated cluster along the Great Essex Road, in many short rows, more in Mile End than in Whitechapel. The road’s frontages were both convenient for City-based charities and benefactors, and prominent to passers-by. Indeed, Robert Wilkinson, writing early in the nineteenth century, had Whitechapel Road in mind when he wrote: ‘A stranger can neither enter nor depart out of the capital, by any road, but his eye is attracted by some humane establishment or other. Almshouses, Hospitals, and Public Schools present themselves in every direction’.[31]

There were Whitechapel’s parish almshouses (1614), Meggs’s Almshouses (1658), Pemel’s (Drapers’ Company) Almshouses (1698), and, just to the north, Fisher’s Almshouses (1711). There were also Yoakley’s Buildings at Mile End Green (1801), John Baker’s (Brewers’ Company) Almshouses on Stepney Way (1826), and the Emanuel (Jews’) Almshouses on Wellclose Square (1849).[32]

Whitechapel’s first parish workhouse on Alie Street opened in 1724, but it was an almost immediate failure. A petition to form a select or closed Vestry, to give Whitechapel’s wealthier ratepayers greater control, in part to permit them to build a new workhouse, gave rise to Parliamentary interrogation in 1734 regarding disputes about the setting of poor rates. (Sir) Clifford William Phillips, a Leman Street distiller and magistrate, estimated that there were somewhat more than 2,500 houses in the parish, most inhabited by labouring people, 1,357 of which were assessed as liable to pay poor rates. Nathaniel Fowler, a collector of duties in the port and a former churchwarden who lived in Prescot Street, said 1,178 householders had paid these rates. He broke down these ratepayers into four classes. ‘The 1st Class was composed of Gentlemen of Fortune, Sense, Reputation, and good Manners: The 2d Class were Tradesmen of good Credit, great Dealings, and, most commonly, of good Understanding. … The 3d Class were Tradesmen of lower Degree, such as Artificers, Carpenters, Bricklayers, Glasiers, and Painters, &c. Out of this Class generally the Churchwardens, and other Officers, were chosen. The 4th and last Class were a large unruly Herd of Men, some of whom are scarce rational, or most commonly act as if they were not, having but little Knowledge and Experience in Accounts; who support the 3d Class above-mentioned when they have any Point to carry, or Purpose to serve.’ The poorer majority of householders, let alone inhabitants, was not spoken of, save that Phillips returned to add that ‘Ragg-fair draws Numbers of Scotch and Irish into the Parish, who live in an idle Way’, arguing that an effective workhouse would deter them from coming into Whitechapel. The Vestry remained open and it was 1763 before legislation was passed to permit a new workhouse, which opened in 1768 on the north side of Whitechapel Road next to the parish almshouses. In 1778 the parish supported 449 children under the age of six.[33]

The Poor Law of 1834 caused Whitechapel to be brought together with Spitalfields and other districts to form the Whitechapel Union. A much larger new workhouse, all but entirely in Spitalfields north of Thomas Street and the former Quakers’ Burial Ground, was built in 1855–60. There was also a short-lived privately run Jewish workhouse on Wentworth Street in the 1870s.

There were many other approaches to poverty relief. The Rev. George Charles ‘Boatswain’ Smith took up the cause of the thousands of sailors who had been cast aside and into penury at the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Homeless and vulnerable to ‘crimping’ (theft and exploitation), such men found help from 1828 through an asylum for destitute sailors on Dock Street, which to some extent paved the way for the innovative and influential Sailors’ Home that opened nearby in 1835.

Around this time cholera stimulated initiatives towards improving living conditions, if just to stem the spread of disease. Thomas Southwood Smith, who practised as a physician at the Eastern Dispensary on Alie Street, reported to the Poor Law Commissioners in 1838 on ‘the close, dirty and undrained courts and alleys of Whitechapel’ wherein ‘large collections of putrefying matters are allowed constantly to remain in the neighbourhood of the houses, and the houses themselves are extremely filthy’.[34] John Liddle (1805–1885), a surgeon and Whitechapel native who served as Medical Officer of Health to the Whitechapel Union from 1838 and to the Whitechapel District Board of Works from its inception in 1855 before retiring at the age of seventy-seven, campaigned indefatigably for better sanitation and housing. Disease was linked to dirt in places like the alleys and courts south of Rosemary Lane, north of Whitechapel High Street, or east of Leman Street, but for decades there was little official action.[35]

There were bread riots in Whitechapel in 1855, but it was the ‘hungry forties’ that were remembered in 1912, when, looking back, Whitechapel was said to have attained a far better social and moral condition. Desperate poverty prompted other early-Victorian campaigners to pioneer practical routes towards bettering the lot of the poor in reforms that are comparatively little known in the historical shadow of the facts and rhetoric of the nineteenth century’s last decades. The parish of St Mark’s, formed in 1841 and covering Goodman’s Fields, was regarded as the poorest division of Whitechapel by its vicar, the Rev. John Lyons, in 1849. His church became a base for early Christian socialism. From St Mary Matfelon, the parish church, the Rev. William Weldon Champneys, a leading evangelical slum parson, brought many reforms and new institutions to Whitechapel, from a mothers’ meeting, to ragged schools, and a coal club and shoe-black brigade. He battled cholera and house farmers and founded the Whitechapel Association for the Promotion of the Health, Comfort and Cleanliness of the Working Classes in 1850. It highlighted overcrowded lodging houses and persuaded some landlords to co-operate in improving living conditions. Reports that a Jewish soup kitchen was established in Leman Street in the 1850s have not been corroborated. The George Yard Mission and Ragged School behind 87–88 Whitechapel High Street, founded in 1854 by George Holland, an evangelizing Nonconformist grocer, was another early and sustained endeavour to address the travails of Whitechapel’s poor. He dispensed charity without making judgements as to the ‘deserving’ or ‘undeserving’ character of the recipients, most of whom were acutely poor. But the challenge was immense. In 1853 The Builder reported, ‘Whitechapel is on the north and south divided by many streets and narrow courts, which are inhabited by very poor people, many of whom are weavers, Irish tailors, Jews, costermongers, dock labourers, and thieves: the great extent of this destitution is alarming.’[36]

This kind of description spread, grew elaborated, and established in the minds of middle-class readers an idée fixe as regards Whitechapel. John Hollingshead’s Ragged London in 1861 is a representative early example worth quoting at length. ‘There are many different degrees of social degradation and unavoidable poverty, even in the east. Whitechapel, properly so called, may not be the worst of the many districts in this quarter; but it is undoubtedly bad enough. Taking the broad road from Aldgate Church to old Whitechapel Church, a thoroughfare, in some parts, like the high street of an old-fashioned country town, you may pass on either side about twenty narrow avenues, leading to thousands of closely-packed nests, full to overflowing with dirt, and misery, and rags. Many living signs of the inner life behind the busy shops are always oozing out on to the pavements and into the gutters; for all children in low neighbourhoods that are not taken in by the ragged and other charity schools are always living in the streets: they eat in the streets what little they get to eat, they play in the streets in all weathers, and sometimes they have to sleep in the streets. Their fathers and mothers mope in cellars or garrets; their grandfathers or grandmothers huddle and die in the same miserable dustbins (for families, even unto the third and fourth generation, have often to keep together in these places), but the children dart about the roads with naked, muddy feet; slink into corners to play with oyster-shells and pieces of broken china, or are found tossing halfpennies under the arches of a railway. The local clergy, those who really throw themselves heart and soul into the labour of educating these outcasts, are daily pained by seeing one or more drop through into the great pit of crime; and by feeling that ragged schools are often of little good unless they can give food as well as instruction, and offer the children some kind of rude probationary home.’

One member of that local clergy, the Rev. Charles Voysey, once a Whitechapel curate, recalled the early 1860s in an account of Goodman’s Fields: ‘St Mark’s, Whitechapel, when I was there, was a parish containing about 16,000 inhabitants, packed into a small space which you could easily walk round in ten minutes. There were only half a dozen streets, or bits of streets in which it was possible for persons in our class of life to dwell, and these were chiefly occupied by Jews. The rest of the streets were occupied by the poorest of the poor, and intersected in all directions by courts and alleys, some of which were of the foulest description. One portion of the parish was almost exclusively occupied by Irish Roman Catholics, the majority of whose families always went barefoot and in rags.’[37]

Voysey looked back from better times to chronicle the poverty he saw in the early 1860s in some detail, not in a quantitative way, but by anecdote and with direct accounts of individuals. He concluded, ‘Above all, in spite of their little feuds, they love each other as brothers and sisters, and put our coldness and selfishness to shame.’[38] This might be contrasted with Henrietta Barnett’s later recollection of her arrival in Whitechapel ten years on in 1873, where a nameless and generic description of deprivation is followed by ‘In these homes people lived in whom it was hard to see the likeness of the Divine.’[39] There is sentimentality in Voysey’s memories, no doubt, but so there is in less intimate accounts of the ‘outcast’ and the ‘abyss’. In more sensationalist writing, bigotry and racial slurs were common.

The literature on Whitechapel’s poverty is too large to detail here; the best overview remains Gareth Stedman Jones’s Outcast London (1971). Disease and sanitation were continuing preoccupations. In the three years to 1864 Liddle attributed 578 deaths in Whitechapel to ‘fever’. Commercial collapse in the 1860s, in sugar refining first then more generally following the financial crash of 1866, intensified poverty. Even while population declined, overcrowding persisted, because incomes fell and rents increased.[40]

Nowhere in London was religious and philanthropic intervention more concentrated. William and Catherine Booth began their Christian Mission (later the Salvation Army) in a tent on the disused Quaker’s Burial Ground in 1865, securing premises on Whitechapel Road in 1868 from which soup and other welfare was provided. Based on his experience at St Mark’s from 1864 to 1871, the Rev. Brooke Lambert published seven sermons titled Pauperism (1871). His successor, George Davenport, echoed Voysey in 1883: ‘there are many thieves and people with no ostensible means of subsistence. But amongst all, and especially amongst the little children, there is very much that is truly amicable and lovely – indeed they are singularly affectionate and gentle.’[41]

The Rev. John Richard Green (1837–1883), best known as a social historian, was the incumbent at St Philip’s Church in 1865 to 1869, his third east London parish, from where he too nurtured reform-minded aims. Edward Denison (1840–1870) spent eight influential months living close by in lodgings in Philpot Street in 1867–8 in the belief that only if people like him lived among the working classes might classes combine with a common purpose of social improvement: ‘Build school-houses, pay teachers, give prizes, frame workmen’s clubs, help them to help themselves; lend them your brains’.[42]

The Rev. Samuel Barnett and his wife, Henrietta Barnett, are perhaps best known among those who sought to address poverty by living among the poor. From 1873, from their base at St Jude’s on Commercial Street, the Barnetts’ vigorous activism led to the establishment of both Toynbee Hall and the Whitechapel Art Gallery, initiatives that reflect their connections, access to funds, and commitment on behalf of the ‘respectable’ poor to moral and educative uplift, as well as to a consequential architecturally self-conscious approach to improvement. But they were relative latecomers and comparatively ineffectual in terms of direct poverty relief.

Andrew Mearns’s pamphlet of 1883, The Bitter Cry of Outcast London, had huge impact, aided by some exaggeration and misrepresentation. Within a year ‘slumming’ was in use as a pejorative term for visiting Whitechapel and similar places with charitable or philanthropic purposes, or none. Against a backdrop of immigration, slum-writing was otherwise much fictionalized, and from 1888 the Jack the Ripper murders reinforced prejudices. Whitechapel’s presentation as exotic became extreme, and deliberately titillating. At night it was said to be full of ‘gaudily-dressed, loud-mouthed, and vulgar women, strutting or standing at the brightly-lighted cross ways’.[43] Margaret Harkness described Whitechapel Road as ‘the most cosmopolitan place in London; and on a Saturday night its interest reaches a climax. There one sees all nationalities. A grinning Hottentot elbows his way through a crowd of long-eyed Jewesses. An Algerian merchant walks arm-in-arm with a native of Calcutta. A little Italian plays pitch-and-toss with a small Russian. A Polish Jew enjoys sauer-kraut with a German Gentile. And among the foreigners lounges the East End loafer, monarch of all he surveys, lord of the premises.’[44]

The stigmatization of Whitechapel obscured comparable poverty away from east London. The Barnetts and others who knew Whitechapel kicked back against depictions of squalor and depravity, stressing monotonous two-storey streets over fetid slum courts, and the dull and unspectacular grind of pervasive poverty, ‘mean uniformity’ to which art could be a palliative. But the poorest did come to be redefined as degenerate, as an unreachable ‘residuum’, with the Barnetts implicated in differentiations that led to Charles Booth’s judgmental classifications of poverty. One architectural consequence was hostel building, another was the enlargement and rebuilding of Leman Street Police Station in 1890–1.[45]

From 1886 Charles Robert Ashbee was at Toynbee Hall, from where he established the Guild and School of Handicraft in a warehouse on Commercial Street in 1888. He published a utopian novel in 1892 titled From Whitechapel to Camelot. It tells the reader little about Whitechapel, rather prefiguring Ashbee’s escape to the Cotswolds in 1902. In the interim he founded the Survey of London with projects elsewhere in east London, so also unrevealing about Whitechapel.

‘Dark’ Whitechapel persisted, including among other socialists. Jack London’s The People of the Abyss of 1903 was an American take on the East End. Rosa Luxemburg, in London in 1907 as a Polish delegate to a Russian Congress, was excluded from what she called a ‘preliminary scuffle’ on Fulbourne Street, so sat alone in a restaurant and wrote a letter to Konstantin Zetkin, describing her view of ‘the famous Whitechapel district … a strange and wild part of the city. It’s dark and dirty here … in the darkness the brightly coloured restaurants and bars give off an eerie glow. Groups of drunken people stagger with wild noise and shouting down the middle of the street, newspaper boys are also shouting, flower girls on the street corners, looking frightfully ugly and even depraved … are screeching and squealing.’[46]

Darkness, of course, remained real, at least at night, though street lighting did improve. Grinding poverty too continued to be all too real. Not long after Luxemburg’s visit the National Insurance Act of 1911 led to the building of 271–273 Whitechapel Road in 1913–14, large premises for the Prudential Assurance Company to pay out benefits, a landmark on the road to a welfare state behind a proudly classical façade.

In spite of continuing deprivation, early twentieth-century Whitechapel evoked affection from such as Emanuel Litvinoff who grew up there. In 1938 William Cameron wrote ‘Some districts give you the impression of having crumpled up under the pressure of poverty. Sometimes a whole street seems to be lying as if crushed, and even their shabby windows have a way of looking at you with shame and humiliation. Streets are like people, and some of them can’t stand being poor. But the meanest street in Whitechapel has a positive quality that you will find nowhere else in London.’[47]

The history and mythology of poverty in Whitechapel retained purchase. Whitechapel’s lowly position on the Monopoly board as adapted for the UK in 1936 must be mentioned. Writers continued to draw on old tropes, from Leslie Paul, recalling his youth in the 1920s with picturesque orientalism in Angry Young Man (1951), to Geoffrey Fletcher referencing Jack the Ripper in 1970 before exhorting his Daily Telegraph readers to ‘visit Whitechapel now for a living slice of the Victorian East End’.[48]

‘This is Whitechapel’, an exhibition in 1972 at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, at that time dependent on the Arts Council and the GLC, brought together local and visiting luminaries to present Whitechapel in photographs, poems and prose. In the words of Edith Ramsay, a local councillor, activist, and latter-day slum-worker, this was a ‘place in which you are glad to have your home. … Colourful streets, people of varied races and cultures, historic buildings, make a walk round the area a fascinating experience’.[49] The catalogue explained: ‘You will find Whitechapel not only in the streets but also in the houses, pubs, labour exchanges, on the buses, in the markets and in the schools. Take a walk along the waste. There are few bomb-sites left where children play but you will still see them playing. You’ll see meth drinkers, you’ll see the market, the shops and the stalls. You’ll see the mothers shopping and shouting at the kids. You’ll see the station, the hospital, the breweries, the pubs and the churches, but most of all you’ll see people. People who know what it is to go without and sometimes dodge the rent man. People who learnt the hard way but have also learnt to make the most of things. Keep their chin up and struggle on. Laugh at themselves. There’s nothing to lose.’[50]

A month earlier, in June 1972, an exhibition of Ron McCormick’s photographs of Whitechapel titled ‘Neighbours’ had opened in the foyer of the Half Moon Theatre on Alie Street. A year later McCormick and others collaborated on ‘Inside Whitechapel’, another exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, presenting ‘the life of a London village told in photographs’ with a conservation message: ‘The big danger with demolition is that the heart is literally knocked out of the place, that too much of the past is sacrificed in the name of progress.’ It concluded rhetorically, ‘When Whitechapel is rebuilt it will belong to the people who live there. It will be their own. Nothing to do with outsiders.’[51] That has not transpired, but the aestheticized neo-slumming of the early 1970s was influential, and different to what was happening in neighbouring Spitalfields which had drawn the Survey of London (volume 27, 1957) and generated conservation battles in the 1970s.[52]

In Whitechapel, where gentrification lagged by a generation, Ripperology remains bankable. There are shops that play on the epithet, and a museum devoted to glorifying the vile episode was underhandedly opened on Cable Street in 2015. Jack the Ripper tours remain popular, moving online in the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020–1. Crime as such is not addressed here, other than to point out that it is not necessarily linked to poverty. Henry Wainwright, a successful brush-maker, murdered Harriet Lane, his mistress, on the site of 130 Whitechapel Road in 1874. For a time, this was Whitechapel’s most notorious crime.

HOUSING

Much has been made of the genteel aspects of other east London suburbs, but affluence in Whitechapel up to around 1800 has been overshadowed by later history. Two great houses were built close to the City in the 1590s, William Megges’s Harte’s Horne and Franchiotto and Deane’s southerly mansion, which passed to Thomas Swallow. In 1666 the Harte’s Horne had fifteen hearths with a ten-hearth annex, and Swallow’s house had sixteen hearths, with three empty ten-hearth properties adjoining. There was then only one other comparably large assessment in the parish, Matthew Bateman’s of sixteen hearths, probably an inn. Seven other properties had ten or more hearths, including Leonard Gurle’s house on Brick Lane and Richard Abell’s on Rosemary Lane, some of the others were inns. Another late sixteenth-century house of eight hearths north of Whitechapel High Street was reputed, perhaps baselessly, to have been a residence of the Earl of Essex. William Rowland built a short row of four five-hearth houses on the north side of the Whitechapel Road in the early 1640s, one for himself, No. 187 appearing to be a much-altered survivor, and Abell built a group of nine eight- to ten-hearth houses on the north side of Rosemary Lane in the years around 1670.

A broadside of 1678 claimed 291 houses had been built in Whitechapel from 1620 to 1656 and 423 more from 1656 to 1678. The overall number of houses in the parish reportedly rose from 1,876 in 1708 to more than 2,500 in 1734, on to 3,689 in 1801. The vast majority of these were of course much smaller than those that have been highlighted. Hearth-tax returns indicate that the total number of households in the parish of Whitechapel (excluding Wapping) was 2,482 in 1664, with an average of 2.4 hearths per household, rising to 2.8 in 1674, still leaving Whitechapel among London’s humblest places by this measure. In 1666 sixty per cent of Whitechapel households had just one or two hearths, only six per cent had six or more. Subdivision for multiple occupancy of around fifteen to twenty per cent of houses can be deduced.[53]

After 1700 and the development of Goodman’s Fields, the best houses in Whitechapel, including around a dozen five-bay double-fronted mansions, were on Mansell Street’s east side, Leman Street’s west side, Alie Street’s south side, and Prescot Street. Wellclose Square, also newly built up, was less grand, but also had at least one five-bay house, which pertained to (Sir) John Parsons. All this has gone, save a single Baroque mansion at 57 Mansell Street, a rebuilding of 1720 and 1741, the scale and grandeur of which is a last indicator of the area’s former cachet. The associated sources of wealth in overseas trade, including in slaves, are typical. There were many sea captains who maintained addresses hereabouts and many with East India Company connections also resided in Goodman’s Fields and Wellclose Square, though some of these people perhaps never went to sea.

A surviving row of the 1720s at 30–44 Alie Street illustrates two house types, of ten and four rooms, behind deceptively similar fronts. Later Georgian houses across the London Hospital estate are as divergent in scale and almost as homogeneous in streetscape terms. As wealth fled in the nineteenth century, speculative housebuilding per se became a comparative rarity. Only eighty-four houses were built in Whitechapel from 1839 to 1842.[54]

Hostels

Roadside inns were an important presence from at least the fifteenth century. There were galleried and spacious inns at the Boar’s Head, the Red Lion, the Spread Eagle, and the Swan with Two Necks (later the White Swan) on the High Street, and at the Nag’s Head, which adjoined another inn, the Green Dragon, on Whitechapel Road opposite the parish church, all with sixteenth-century or earlier origins. They hosted stagecoach stands, and coach, carriage or chair hire. Livery stables were a consequential spin-off, as behind the White Hart, on the High Street’s south side, and the Black Horse on Leman Street from the 1680s. There were also coach-makers on the south side of Whitechapel Road east of the church.[55]

A unique kind of hostel, and a canary in the mine for de haut en bas intervention to ‘improve’ the lot of the unfortunate, was the Magdalen Hospital for the reception of penitent prostitutes, established on Prescot Street in 1758. This reformist refuge had 136 beds before it moved to Southwark in 1772.

The subdivision of houses, many of which were anyway small, was already widespread in the seventeenth century. No clear line can be drawn between multiple occupancy and lodging houses, though the latter came to be more formally identified by the eighteenth century when overcrowded lodgings were prevalent. Sugarhouses often had ancillary ‘men’s rooms’ or dormitory ranges, often purpose-built. What came to be called common lodging houses were typically converted houses with dormitories over common kitchens to accommodate migratory or casual workers, some of whom stayed for long terms. They were increasingly associated with crime and prostitution, which led eventually to attempted regulation via the Common Lodging House Acts of 1851 and 1853. It was reported in 1876 that one fifteenth of the population of the district of Whitechapel, more than the parish so somewhat more than 5,000 people, slept in 167 registered common lodging houses, a number that had fallen to eighty-six in 1894 when the LCC took over regulation. The decline is to some extent explicable by the spread of hostels against the backdrop of a falling population.[56]

Purpose-built hostels became a distinctive feature of Whitechapel in the late nineteenth century. A major forerunner, of much wider significance as an innovative form of this building type, was the Sailors’ Home at the south end of the parish. It opened in 1835 with a capacity of 100 and was enlarged and extended to Dock Street in 1865 to accommodate 502. It housed more than 10,000 boarders annually in the 1870s and provided a model for other such institutions in London and beyond.

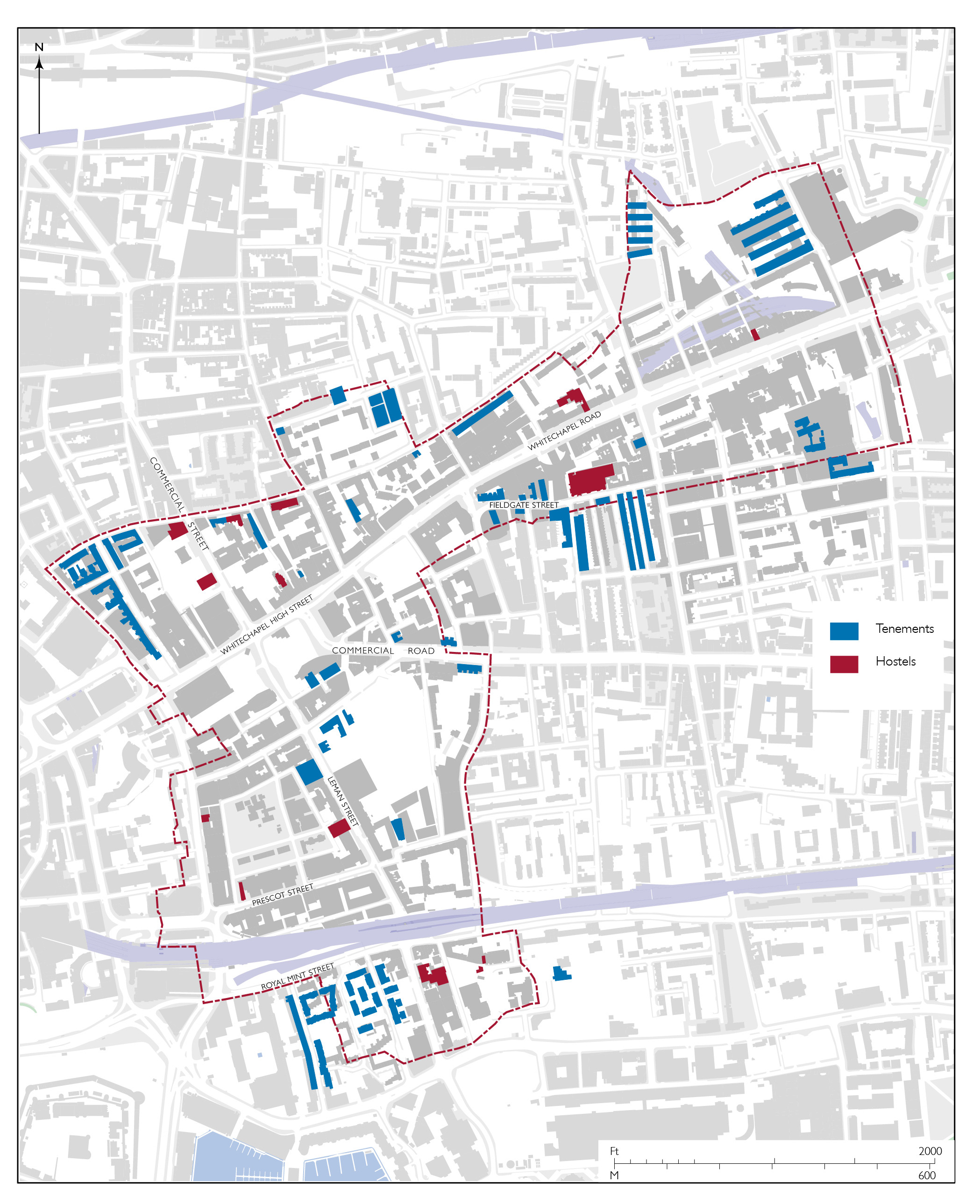

Map of purpose-made hostels and tenement dwellings in 1914 (drawing by Helen Jones)

A warehouse on Commercial Street was converted in 1888 by the Victoria Homes, a philanthropic venture headed by the Hon. Granville Augustus William Waldegrave, 3rd Baron Radstock, for an austere new type of model lodging house with a capacity of 500. A second Victoria Home opened on Whitechapel Road (1897), with beds for another 500. Gustav Wildermuth, who had run a lodging house in George Yard for twenty years, opened Wildermuth House (1893) at the east end of the south side of Wentworth Street. This private venture was a model lodging house for single working men, accommodating almost 400. The Rowton House on Fieldgate Street (1902), a ‘monster doss-house’ and one of six in London, was a cut above and also aimed to make a modest profit. It provided lodging for 816 men in cubicles that granted privacy – at 6d a night it was quite expensive. It still stands, converted to flats.

The Jews’ Temporary Shelter, which grew out of Simcha Beker’s Home for the Outcast Poor, for Jewish migrants newly arrived in London, in ad hoc premises on White Church Lane in the early 1880s, established itself in a house on Leman Street (1886). The Shelter was enlarged (1906), then it moved to purpose-built premises on Mansell Street (1930) with dormitories for 130 men and women. By 1937 the Shelter had accommodated over 100,000 migrants, many on their way to America and South Africa. It left Whitechapel in 1973. The Jewish Association for the Protection of Girls and Women rebuilt a Prescot Street house as Sara Pyke House (1899), a hostel in which 236 ‘respectable’ Jewish girls were housed. The Association expanded to premises on Mansell Street in 1914.

The Salvation Army had opened a women’s refuge, the Hanbury Street Shelter (1884, outside Whitechapel). This became known as Hope Town and moved into Whitechapel in a conversion of the Chicksand Street School (1931), accommodating 305 women. Hopetown moved again to Old Montague Street (1979, rebuilt 2007), and was renamed Founder’s House when men displaced women (2017). The Salvation Army also took over the Whitechapel Road Victoria Home (1919) and built a large additional hostel to its west (1967) with 252 cubicles. After rebuildings (1996 and 2002) this closed in 2018.

The Working Lads’ Institute (1885) on Whitechapel Road was acquired by the Rev. Thomas Jackson, a Primitive Methodist, in 1897 and adapted to include dormitories for homeless teenage boys. A decade later Jackson set up the Whitechapel Mission in a church just east of Cavell Street, incorporating a night shelter from 1923. That site was redeveloped (1971) to include hostel accommodation, and has remained a day centre for the homeless since 1995. For a very different section of the population, four nurses’ homes were erected between 1884 and 1918 to the south of the London Hospital either side of Stepney Way. These specialized hostels housed 446 nurses in 1911.

A short-lived hostel was the Hindustan Community House established in 1940 but bombed out in 1943. It was a conversion of the Gower’s Walk Free School, primarily to house Bengali sailors, but, as the name suggests, a Gandhi-an initiative. In another conversion of a school, the Colonial Office opened a small hostel on Leman Street (1942) for Black seamen from British colonies in West Africa and the West Indies, victims of racism elsewhere. After controversy and debate, it closed in 1949. In the 1950s there were privately run lodging houses on Wellclose Square and Ensign Street, for Bengali and Somali seamen, respectively. Finally, Wynfrid House on Mulberry Street (1970) is a hostel attached to the adjacent German Catholic Church.

The much rebuilt but long-lived Sailor’s Home was adapted in 1978 as a hostel for single homeless men, with a block of transitional flats added on Ensign Street in 1995. The parent building was converted in 2014 into a youth or backpacker hostel. In addition, the Dellow Centre opened in 1994 on Wentworth Street to provide shelter and services for the homeless. It is a successor to Providence Row, a Catholic foundation that had been based in Spitalfields since 1868.

Slum clearances and tenement dwellings

Nineteenth-century rail and road improvements were a standard method of clearing poor housing. To make way for the London & Blackwall Railway below Goodman’s Fields in the late 1830s about 150 houses in densely packed courts were pulled down and a further seventy houses, inhabited by some 700, were removed from the south side of the line in 1861. Yet the local population remained little changed as displaced people obtained rooms in other houses in the district.