United Standard House

mid 1960s former office building, demolished 2017–18, on the site of the Elizabethan Boar's Head playhouse | Part of Cromlech House and United Standard House

Boar's Head Playhouse

Contributed by Survey of London on Aug. 3, 2020

A late-Elizabethan playhouse, the Boar’s Head, stood just east of the south end of Petticoat Lane. On that account the early history of the immediate area has been exhaustively investigated.1 First incursions behind Petticoat Lane to the east here were probably associated with houses on Whitechapel High Street. Thereafter, the most notable and substantial development was of an extensive yard behind the Boar’s Head Inn which lay on the site of the future 141–144 Whitechapel High Street, near the corner. This had probably taken place by the 1530s, when John Transfeild, a gunner in the service of Henry VIII, appears to have acquired a connection to the property. While in Ireland in 1557, Transfeild gave permission for the staging of a ‘Lewde Play called a Sackfull of Newes’ in the inn yard of the Boar’s Head, This brought the unwanted attention of the Lord Mayor, who briefly imprisoned the players. Transfeild died in 1561 and his widow Jane (née Grove), married Edmund Poley, who had the copyhold of the Woodlands estate of which, or part of which, Transfeild appears to have been a leaseholder. In 1594 Jane Poley, again widowed, granted a lease of the Boar’s Head inn that ordained the building of a public playhouse. By this time there were already several houses on the west side of the inn yard, in one of which she took up residence; she died in 1601.2

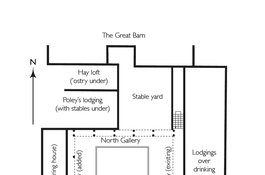

The lease of the inn was to Oliver Woodliffe, a haberdasher and financial speculator, for twenty-one years from March 1595. It required Woodliffe to spend £100 within seven years building a tiring house (dressing rooms) and stage. The decision to proceed, despite threatening noises from the Lord Mayor, may have been encouraged by the demise of the Burbages’ Theatre in Shoreditch in 1597. Before work started, the Whitechapel High Street frontage covered what would become Nos 141 to 144, a range of two-storey buildings including, from the west (Nos 142–144) a hall, parlour and kitchen below three chambers. Beyond was the inn’s entrance with a room over, and then the end of a building (No. 141) that stretched northwards to face the yard’s east side. This had a drinking room, three parlours, a cellar and three stables below seven chambers with access from a gallery. Remains of what is believed to be this building were discovered during archaeological investigation in 2018. A lateral barn enclosed the yard’s north side, the west side had an ‘ostry’ (probably the inn’s public stable) adjoining other stables reserved to Poley and Woodliffe. There was also a garden that had likely once pertained to one of the High Street houses.3

Woodliffe sublet the inn and part of the yard to one Richard Samwell who built narrow galleries north and south, while Woodliffe built one on the west side and a simple rectangular stage, 40ft by 25ft, in the middle of the yard. The existing eastern gallery leading from the back of the inn formed the fourth side. This arrangement separated the inn and the theatrical enterprise, and meant that neither man was entirely liable for the legally questionable structure. No sooner had it been built than Woodliffe took up with a theatrical entrepreneur, Robert Browne, leader of the Earl of Derby’s men, and a more substantial playhouse was built in 1599, the year the Globe opened at Bankside. Constructed by a carpenter, John Mago, at a cost of around £520, this had seven-foot-deep galleries and a tiring house on the west side adjoining a new stage with a tiled roof. The galleries provided only about a third of the accommodation. Overall, the Boar’s Head was similar in size to the Fortune, the contemporary playhouse on the edge of the City to the north- west.4

The Earl of Derby’s men played at the Boar’s Head in the winter season when it was permitted, but most of the drama was taking place in the courts, where Woodliffe, Browne and Samwell were embroiled with an investor, Francis Langley, who had hoped to exploit the ambiguous title to the inn and theatre. Difficulties were compounded by a Privy Council order in 1600 forbidding acting in inns, and matters further complicated when Browne went on tour, subletting to the Earl of Worcester’s Men. Langley died, then in 1603 Woodliffe and Browne, who had returned with his players, suing and countersuing one another, were both carried off by the plague.5 The Boar’s Head continued as a playhouse. Browne’s widow, Susan (née Shawe), who held the lease, married Thomas Greene (d. 1612), a member of the Queen’s Men, and in 1607, even after the Queen’s Men had departed for the Red Bull in Clerkenwell, ‘comon Stage Plaies … are daylie showed and exercised and doe occasion the great Assembleis of all sortes of people’.6 Once again a widow, Susan Greene, who may have retained at least part ownership, married James Baskervile in 1613. Further information is elusive up to 1616 when the lease reverted to Jane Poley’s son, Sir John Poley. Following a loosening of manorial constraints on copyholders, Poley was able to agree in 1618 to enfranchise most of the Boar’s Head property.7

The tiring house and stage were probably pulled down in 1621 when Poley sold the land on which they stood as sites for small houses. The purchaser was William Browne, who already held the house on the site of 145 Whitechapel High Street, immediately west of the Boar’s Head Inn. The eastern galleried range survived into the eighteenth century. The Boar’s Head name, like those of many other former inns, endured long after inn use ceased.8

-

Herbert Berry, The Boar’s Head Playhouse, 1986 ↩

-

Berry, pp.11–17,21–2 ↩

-

Berry, pp.24,26–30,77,95–8,155: information kindly supplied by David Sankey ↩

-

Berry, pp.30–36,106–09 ↩

-

Berry, pp.37–46,55,63–9 ↩

-

as quoted in Berry, p.74: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography sub Baskervile and Greene ↩

-

The National Archives, E135/23/78: Berry, pp.76–8 ↩

-

Ancestry, London Metropolitan Archives London wills: Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives, P/SLC/1/17/13–14: Berry, p.80 ↩

Clay pipe kiln

Contributed by david2 on Nov. 29, 2019

During archaeological excavations of the "Boar's Head Playhouse" (an Elizabethan theatre, most of which is preserved and protected) I was a "relief supervisor" on this site, popping in on occasions that the archaeologist in charge (Heather Knight) had to attend to other duties. So it was that I ended up supervising people digging up this 18th-century clay pipe kiln. It dates to the period after the theatre had closed and when the area was becoming a warren of small enterprises. In over thirty years digging, I haven't seen so complete a clay pipe kiln. They're mostly small backyard affairs and pipe makers would buy in china clay, and then sell on pipes, as small family businesses. This 3D model, with notes, gives a good impression of the sort of multiphase sites we have in London, with later 19th-c brickwork left in place too. Anyway, here's a link to the model https://skfb.ly/6OBMD

Animation of the Boar's Head playhouse stage

Contributed by Survey of London on Feb. 21, 2019

The Boar's Head playhouse was built in 1599 within the yard of the Boar's Head inn, just to the south of the site of United Standard House. This animation, link below, was created to assess the likely height of the stage, and shows the general disposition of the stage within the yard.

United Standard House

Contributed by ewan on Oct. 19, 2018

Designed by J. Ockwell, an associate with R. Seifert & Partners. c.1960.

Cromlech House and United Standard House

Contributed by Survey of London on June 5, 2019

The site of the Travelodge London City was cleared after the Second World War of the bomb-damaged portion of Brunswick Buildings, Goulston Street, the 1880s warehouses at 16 to 36 Middlesex Street, a single very large warehouse at 8 to 14 built in 1886-7 for Hollington Bros, wholesale clothiers, and 140 to 145 Whitechapel High Street, cleared later and rebuilt with single-storey shops demolished c1990.1 The site behind the High Street was in use as a car park by 1947, and by market stalls on Sundays. The first rebuilding was a solitary four-storey showroom and workshop building at 16-20 Middlesex Street in 1954-5.

Shortly after the war Petticoat Lane Rentals had taken a lease of the cleared site between Goulston Street and Middlesex Street as a car park and as a site for market stalls on a Sunday. By 1952 the site was scheduled under the Stepney comprehensive development plan for a warehouse and office building, but it was not until 1961 that the developer City and Country Properties Ltd secured outline planning. The scheme, designed by G. A. Crockett, architect, was for a double-height sunken market hall with gallery at street level for more stalls, in plan fanned out towards the north end, with a delicate Festival of Britain diamond-patterned glass roof. To the south was a tower of offices in a similar style, with a zig-zag profile roof of concrete shell with two double-pitches and oversailing up-pitched eaves. It had seventeen storeys of offices above first-floor restaurant and ground-floor shops, all curtain glazed around a lift core. On the Middlesex Street frontage of the market hall was a three-storey curtain-glazed building with showrooms on its upper levels. To the south of the tower was to be a sunken garden and access to basement parking, with a loading bay on the Goulston Street side of the market hall.2 A revised scheme received planning permission for the new owner, Cromlech Property Company Ltd, and construction began in 1964, when the 80-year covenant imposed by the Metropolitan Board of Works when they sold the Goulston Street frontage on which James Hartnoll built Brunswick Buildings restricting the site to flats for the ‘industrial classes’ expired.

The conjoined buildings that went up – United Standard House to the south and Cromlech House to the north - to the designs of J. Ockell of R. Seifert and Partners, architects, was more typical of the 1960s than Crockett’s more elegant design of 1961. The office portion, United Standard House, was in a slab block, six storeys over a three-storey and four-storey podium covering the entire site (leaving a light well behind the 1955 building at 16 to 22 Middlesex Street), faced in yellow brick like the side of the slab block, with continuous high-level strip glazing. The ground floor was mostly open beneath the podium, space for car parking and market-stall storage, the exception being the base of the tower.

The tower’s principal tenant was United Standard Insurance Co. Ltd, and with other insurance companies and, in the 1960s and 1970s, shipping agents predominating, reflecting Whitechapel’s status at the period as ‘the centre of the commercial marine business in Britain’.3 Cromlech House was more typical of commercial Whitechapel, with Daylin shirt manufacturers in the 1960s and 1970s, L. Frankenberg, warehousemen - who sold their Houndsditch headquarters in 1971 and moved to Cromlech House - and in the final days, Pemberman’s caterers.4

Petticoat Lane Rentals were wound up in 2008 and United Standard and Cromlech Houses were empty for 10 years pending redevelopment, which was completed in two phases, starting at the north end with Cromlech House, site of the Travelodge.5

-

London Metropolitan Archives, District Surveyor's Returns: Post Office Directories (POD): East London Observer, 29 Oct 1887, p. 5 ↩

-

Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives, Building Control file 15911: The Times, 15 June 1961, p. 8: Paul B. Fairest, ‘Planning Permission and Existing Uses – Enforcement Notices', Cambridge Law Journal, vol.29/2, Nov 1971, pp. 201-03 ↩

-

POD: https://surveyoflondon.org/map/feature/31/detail/#story ↩

-

POD: https://www.bizdb.co.uk/company/pembermans-catering-ltd-08342753/: Financial Times, 26 Nov 1971, p. 30 ↩

-

Tower Hamlets planning applications online: http://www.downwell.co.uk/projects/middlesex-st-phase-1/: https://beta.companieshouse.gov.uk/company/00613900 ↩

Demolition - looking west (into the City)

Contributed by david2

United Standard House from the southwest in 2016

Contributed by Derek Kendall

United Standard House and Cromlech House with market stall frames on Goulston Street in 2016

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Shutters on Middlesex Street in 2016

Contributed by Derek Kendall

United Standard House, southwest corner on Middlesex Street in 2016

Contributed by Derek Kendall

United Standard House, entrance on Middlesex Street in 2016

Contributed by Derek Kendall

United Standard House and Cromlech House from the southeast on Goulston Street in 2016

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Inside - dubious quote attributed to "K. Marx" graffiti on fitting

Contributed by david2

United Standard House and Cromlech House from the northeast in 2016

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Boar's Head playhouse, site plan in the late 1590s (drawing by Helen Jones based on plan published by Herbert Berry)

Contributed by Survey of London

United Standard House, detail on Goulston Street in 2016

Contributed by Derek Kendall