Whitechapel High Street - its early history

Contributed by Survey of London on June 11, 2019

Evidence for development before 1500 that can be pinned directly to

Whitechapel High Street is scant, but as its hinterlands were largely

undeveloped until the mid-sixteenth century, it may be inferred that most

early references to Whitechapel refer to the High Street or the west end of

Whitechapel Road. Speculation around the route of the Roman road to Colchester

has ranged widely: it may have followed a line close to the High Street and

Whitechapel Road, or may have followed Hackney Road. The discovery of

Roman metalling in Aldgate High Street supports ancient use of the route, as

does the discovery, about 2m below the level of the High Street, of Roman

funerary urns in 1836. Whitechapel High Street’s early name was

Algatestreet, presumably a reflection of its status as an extension of Aldgate

High Street beyond Aldgate Bars, the gates, latterly vestigial, across the

west end of Whitechapel High Street that marked the eastern boundary of the

City. The land either side of this route was waste of the Manor of Stepney and

probably remained unbuilt on until the thirteenth century when the building

and siting of the ‘white chapel’ might suggest the High Street to the west was

already built up. Taxation evidence indicates that what development there was

had then recent origins.

Algatesetrete is recorded as one of the settlement areas of the Manor of

Stepney in 1348-9. Some indication of the character of landowners and uses

in the High Street is given by property transactions of this universally

transformative period, the time of the Black Death. Predictably, perhaps,

property holders tended to be wealthy merchants, already possessed of

substantial property and influence within the City, and sometimes with

connections to the Court. In 1350 John de Gosebourn, who was an auditor of the

Exchequer by 1370, was involved in a transfer of unspecified premises in

‘Whitechapel in Algatestrete’, part of a large landholding in Stepney which by

1400 included eighty-six acres, though only a few houses in Whitechapel High

Street. Sir John de Stodeye (otherwise John Stodie), a vintner and

alderman, a Member of Parliament in 1354–7, and Mayor of London in 1357–8,

acquired premises in 1358 ‘in the parish of the Blessed Mary “de Whitchapelle”

without Aldgate, London, and in Stebenheth’, followed in 1361 by a tenement of

Gosebourn’s, ‘by le Whitechappel’. Then, in 1365, Stodeye acquired ‘24

shops and two gardens in the parish of St. Mary “Matefeloum”, without Algate’,

from John Chaucer, another vintner, and his wife Alice – the parents of the

poet. This may have included property that had been left to Alice Chaucer by

her uncle Hamo de Copton in 1349, and so many shops strongly suggests a

location in the High Street. The same is true of a similar transfer of 1375–6

by John de Cantebrigia and Thomas Broun of ‘3 shops with gardens adjoining’ in

‘St Mary’s parish in Algatestret’.

In 1430 property on the north side of Algatestrete in the parish of St Mary

Matfelon was transferred from John Roppele to Margaret Wyngerworth, a widow

who had already held it with her husband from Edmund Bys, a stockfishmonger,

Ellis Clidermore, a citizen mercer and Roppele. The location is given as

between the tenements of John Stamp on the west, the lands of the heirs of

John May on the east, and property of William Haunsard on the north. Haunsard

owned large tracts in Stepney and Whitechapel including a messuage north of

Algatestreet near the City boundary.

A list of alehouses compiled from 1418 to 1440 mentions three in Whitechapel,

the ‘Hamer’ (hammer), an unusual name, perhaps later the Crown and Hammer on

the High Street's north side near present-day Tyne Street, the Swan, perhaps

near the east end of the High Street’s north side, and the ‘hertishorn’

(Hart’s Horn). The ‘Cok’ was also present by the 1450s, probably on the High

Street’s south side. Firmer indications of activity on the north side of the

High Street date from the 1460s. The brewhouse then called the ‘Hertyshorne’

or ‘Herteshorne’ is named in two court cases. It might have been near what

became the east corner with Goulston Street, as a house built there in the

1590s by William Megges bore the name the Harte’s Horn. One case concerns the

property immediately to the east. This was then in the occupation of John

Morth, a bladesmith, and Simon Hollerville, a barber, for a term of eight

years from Christmas 1462, and was held by them from William Couper, a

butcher. The ‘Hertyshorne’ itself was held by William Wolston and Walter

Bodenham (or Bodman), who is described as a citizen Brasier and bellfounder,

but there is no evidence nor is it probable that the brewhouse was used as a

bellfoundry. The other case concerned the brewery’s owners, the Walssh family,

who had acquired it and three shops around 1440 from John Bythewode, a

timbermonger. This appears to have been a reversion. In 1394–5 Nicholas

Walssh, a citizen clothworker, had granted a messuage and shops in Whitechapel

to Christina Bithewode, the widow of a timbermonger, with a remainder to the

Abbey of the Minoresses of St Clare without Aldgate. At the end of all this,

in 1468 Nicholas Walshe granted the ‘Herteshorn’ to the Minoresses.

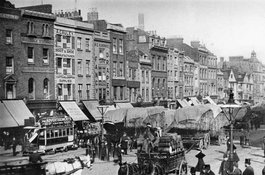

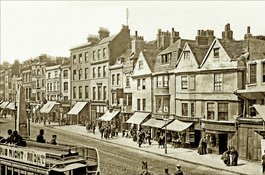

Earliest representations of the High Street, such as Anton van den Wyngaerde’s

panorama of around 1543, are somewhat schematic but conform in depicting a

continuous frontage of mostly gable-fronted houses of two or three storeys.

The only development behind the High Street on the ‘Agas’ map is around what

became Goulston Square, and perhaps represents the ‘Herteshorn’ brewery.

Beyond walled gardens or yards were the ‘pleasant fields’ whose loss by the

end of the century was bemoaned by John Stow. East of the ‘Herteshorn’

site a wall on the ‘Agas’ map conforms with a property line that ran roughly

parallel to the High Street into the nineteenth century. Seventeenth-century

and later maps suggest that this section of the High Street frontage had

evolved, presumably in the thirteenth to sixteenth centuries, as many long

narrow ‘burgage’ plots, but, developing slowly and piecemeal, was haphazardly

laid out and broken by numerous alleys and yards.

Evidence also supports Stow’s assertion that the whole High Street on both

sides was by 1600 ‘pestered with cottages and alleys’. In March 1616

William Hearne of Whitechapel was charged with having ‘presumptuously

endevoured’ to make and erect ‘divers tenements {in} an auntyent stable in a

common Inn called the Redd Lyon in Whitechapel Street contrary to his

Majesty’s proclamacion, and to the great annoyance of parishioners by bringing

poore people there to inhabit, who dying leave their children to be mayntayned

by the parish’. He was ordered to pull down the new chimneys and to restore

the tenements to use as a stable. Others adopted a more positive tone

when describing how, by the 1650s, ‘without Aldgate, there is a spacious huge

Suburb, about a mile long, as far as White Chappell and further’.

Topography of the High Street after 1600

By the 1670s, the High Street’s alleys numbered around twenty. Some, such as

the Nag’s Head Inn yard (on the site of the Relay Building, previously No.

115) and the Swan brewhouse yard (on the site of the Whitechapel Gallery at

Nos 81–82 and returning to Osborn Street) were substantial, while many others

had been or remained unnamed, probably private closes leading to a single

house and its dependent stables, workshops and outhouses. Some such yards had

been lined with small houses and workshops – Bull Alley (on the site of No.

75), Grid Iron Alley (approximately on the site of No. 122), and Harte’s Horne

Court (on the site of Nos 133–137). Typical of these was Three Bowl Alley,

roughly on the site of Tyne Street. By 1623 it was a short alley containing

six small houses. They had been built after 1589 when Thomas Golding sold

two messuages called the Crowne and Hammer (later the Three Pidgeons) and the

Three Bowls, which passed by inheritance to a whitebaker named Ralph

Thickness. In leases of 1697 and 1700 from Thickness’s great-grandson the site

is described as the two houses (the Three Pidgeons and another now known as

the Patten, the Three Bowls having ‘fallen down’), and an entryway between

them leading to stables, workshops, garden ground and an old house that

Thickness had occupied; this had a 12ft by 8ft jettied window at one end.

Three Bowl Alley and Grid Iron Alley, immediately to its west, were eradicated

in the creation of New Castle Street (later Tyne Street) in the early

1730s.

Other such closes developed into proper alleys leading northwards into

Wentworth Street – George Yard (now Gunthorpe Street), Angel Alley (now

truncated), Moses and Aaron Alley and Castle Alley (now Old Castle Street) and

Catherine Wheel Alley (obliterated by Commercial Street).

Whitechapel hay market

Contributed by Survey of London on Aug. 26, 2020

From at least the 1660s until 1928, an enduring and divisive feature of

Whitechapel High Street that spread to streets adjoining was the Whitechapel

hay and straw market, one of the earliest recorded of London’s fodder markets,

after those in Westminster (the Haymarket) and the City of London (West

Smithfield), the former known by the mid sixteenth century, the latter older.

The right to hold markets in Stepney resided with the Lord of the Manor of

Stepney, granted by Charles II in 1664 specifying a weekly market at Ratcliff-

cross. A hay market is reputed to have endured in Ratcliff until 1708, but

according to Daniel Defoe, Whitechapel High Street was already in use as a hay

market by 1665. While A Journal of the Plague Year is not the most reliable

of sources, the Whitechapel portions are reckoned to be those most closely

based on a first-hand account. Defoe claimed that during the Plague, owing to

the scarcity of grass, ‘Hay in the Market just beyond White-Chapel Bars was

sold at 4 l. _per _Load’. A more unimpeachable indication that the hay

market was established in the High Street before the end of the seventeenth

century is the taxation in 1693 of Isaac Blissett, a ‘barrowman’ living on the

south side of Whitechapel High Street adjacent to Peacock Court (approximately

opposite Old Castle Street), ‘for the Hay Market to the Lady of the Manor …

Property assessed: Haymkt’.

Hay was sold from large carts in the High Street. By tradition, a toll of

6_d._ per cart was collected, twopence of which was payable to the Lord of the

Manor. This was codified by the Whitechapel High Street Paving Act of 1770 and

the Whitechapel Improvement Act of 1853, which vested the paving

commissioners’ powers in what became the markets committee of the parish

Vestry. The usual market days, as was the case with the other main hay

markets, were Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday.

The market was confined in its early years to the High Street, described in

the 1770s as a ‘fine wide street … the principal eastern entrance into London

from the great Essex road … the south side of {which} is used for a hay market

three times a week’. This south-side arrangement prevailed, certainly to

the 1830s and probably until the opening of the Whitechapel to Bow tramway in

1870, whose lines ran on the north and south side of the street. Until then,

discord between the hay salesmen and local authorities derived largely from

untidy arrangements of the hay carts.

The tram coincided with wider changes in transport and the hay and straw

business, which saw a proliferation of hay salesmen in London from twenty-nine

in 1833–4 to more than fifty in 1870. Surprisingly few were in Whitechapel,

probably because it was an open market; Essex farmers could bring their hay

directly to Whitechapel to sell. But by 1870 three or four Whitechapel hay

salesmen, led by Gardner of Spread Eagle Yard and Gingell of Kent and Essex

Yard, were in business in a major way, and were operating an effective cartel.

By then Gingell already had a wharf in Shadwell, and a decade later Gardners

had one in Limehouse, reflecting the expansion of their supply chain from

traditional sources in the Essex countryside, as importing hay became

cheaper.

Business was still conducted with farmers in Essex and Hertfordshire, but

those deals were concluded in the shires and the hay and straw transported by

train, and collected by the dealers. Where once hay carts had rolled in,

principally from Essex, many of the carts that took up position in Whitechapel

High Street belonged to the dealers and were stored in their adjacent yards.

In the early and mid nineteenth century many of the carts were two-wheelers

that could be pulled by a single horse. By the later nineteenth century large

four-wheel waggons were the norm.

As early as 1782 the Whitechapel Paving Commissioners were complaining that

hay carts ‘do frequently annoy, obstruct and endanger passengers in carriages

and on horse back’. They produced a scheme for regularising the placing of the

carts abreast in the street, in blocks of three to five carts, a system that

was regularly ignored. With the advent of tramways and generally

increasing traffic, calls for the removal of the market became frequent,

strident and ultimately litigious. From 1870 regular efforts were made to

remove the market, principally by local boards and vestries affected by delays

traversing Whitechapel, but vested interests and the lack of an alternative

site prevented change.

There was some nostalgic affection for the market. In 1902, one William Stout

reported that ‘Whitechapel High Street has long been noted for its Hay Market,

which is the last relic of old English life in the neighbourhood, all else is

foreign. In the whole length of the High Street, … there are no buildings

worthy of notice from an architectural or any other point of view.’

Matters came to a head on 27 May 1905 when officials of Stepney Borough

Council, which had inherited the rights of the Whitechapel hay market

commissioners, moved three carts of Gingell, Son, and Foskett, parked on the

tramlines in the north part of Leman Street, to their Wentworth Street yard

and there destroyed the loads of hay and straw. Gingell, Son and Foskett took

the council to court for compensation and the establishment of their rights

under ancient precedent to conduct the hay market anywhere within the parish

of Whitechapel, which the council disputed on the grounds that some of the

streets into which they wished to expand – Commercial Street, Leman Street in

its present form, and Commercial Road, did not exist when the market was

established. The council lost, on appeal and in the House of Lords, but in

concluding this ‘peculiarly absurd case’ the Lords determined that the

Whitechapel Improvement Act of 1853 did allow the council to move carts when

they caused an obstruction.

An opportunity to buy the manorial market rights arose in 1909, but a

trenchant ratepayers’ campaign prevented the purchase. Three years later

an attempt by the LCC to purchase the market also ran aground. The market

rights were instead acquired by three of the principal hay and straw dealers –

Gardner & Gardner, Gingell, Son and Foskett and Harvey & Willis.

Congestion increased after the First World War, compounded by the location of

a tram terminus. The LCC, wishing to relocate the tramlines to the centre of

the street to accommodate increasing volumes of motor traffic, introduced a

clause in the London County Council (General Powers) bill of 1927 to acquire

the market rights. The fight had no doubt gone out of the hay salesmen, who

agreed to accept the offer £18,000and not to oppose the bill, their market

depleted by the very motor traffic that their carts were impeding: sales of

hay had fallen from 22,500 loads in 1907–8 to 17,761 in 1910. The market

‘succumbed to the motor’ and closed in January 1928. The tramlines were duly

relocated to the centre of the road in 1929. Gardners hung on in Spread

Eagle Yard till 1931 and Gingells were wound up in 1935.

Whitechapel High Street’s obelisk

Contributed by Survey of London on Aug. 26, 2020

A distinctive feature of Whitechapel High Street for sixty years was a stone

obelisk. Purchased by ‘the people of Whitechapel’, that is the parish, in

1853, it had been on display at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in Hyde Park, and

is probably identifiable as the ‘granite obelisk and base, 20ft high, weighing

about 15 tons, of Cornish granite’, exhibited in the external enclosure at the

west end of the building by R. Hosken of Penryn.

It was erected in the middle of the High Street opposite the end of Commercial

Street, surrounded by eight stone bollards, ‘for the protection of foot

passengers’, and generally to provide a ‘rest’ for pedestrians in the middle

of the wide crossroads. It was disparaged in The Builder – ‘rather an

attenuated pyramid than an obelisk: it wants the true _needle _character.’

It also served as a glorified lamp standard, with lights affixed on each side.

It had to be moved in 1883 as it was in the way of works for the District

Railway line. It was re-erected, its lamps replaced by flanking lamp-posts

(also later removed), in a more convenient position between tramlines further

east in the High Street, at its widest point south of No. 83. The obelisk met

an ignominious end in 1913 when it was knocked down by a lorry.

Henrietta Barnett on Whitechapel High Street

Contributed by Survey of London on Aug. 26, 2020

Recalling her arrival in Whitechapel in 1873, Henrietta Barnett remembered

‘Whitechapel High Street, where some forty keepers of small shops lived with

their families. ... There were two or three narrow streets lined with fairly

decent cottages occupied entirely by Jews, but, with these exceptions, the

whole parish [St Jude’s] was covered with a network of courts and alleys. None

of these courts had roads. In some the houses were three storeys high and

hardly six feet apart, the sanitary accommodation being pits in the cellars;

in other courts the houses were lower, wooden and dilapidated, a standpipe at

the end providing the only water. Each chamber was the home of a family who

sometimes owned their indescribable furniture, but in most cases the rooms

were let out furnished for eight-pence a night, a bad system which lent itself

to every form of evil. In many instances broken windows had been repaired with

paper and rags, the banisters had been used for firewood, and the paper hung

from the walls which were the residence of countless vermin. In these homes

people lived in whom it was hard to see the likeness of the Divine.’