'Poor Man's Hotel: A Rowton House Building for Whitechapel'

Contributed by Rebecca Preston on Oct. 19, 2016

'To-morrow the fifth of the Rowton Houses will be opened to receive guests. Situated 400 yards from St Mary's Station, Whitechapel, it stands with its frontage in Fieldgate-st., in the very midst of an enormous population. Within two or three weeks probably every one of its 816 cubicles will be occupied. The rent of 6d. a night, or 3s. 6d. a week, covers the cost of all accommodation by day as well as night. So perfect has been the construction of these Rowton Houses that, except in trifling details, it has not been possible to introduce any improvement in the last building. Without a retrogression, the primary conception has been adhered to of giving each man a separate cubicle with a separate window under his control; and such privacy and such a bed that, in the words of Lord Rowton, an Archbishop might sleep there in decency and comfort. All other accommodation - dining-room, smoking-room, reading-room, and bathrooms - is found on the ground floor. In the locker corridors are fitted the wardrobe cupboards, where each man may keep his clothes and possessions under lock and key. Other conveniences include dressing-rooms, barber's shop, and a room each for shoemaker and tailor, where cheap repairs may be carried out, and new or secondhand goods obtained. The finest apartment in this "Poor Man's Hotel" is the dining-room, which has table room for 456 men. Here anything may be bought at cost price - from cooked meat at 4d. to a farthing's worth of milk or sugar. There are also provided all necessary cooking utensils for the gratuitous use of lodgers desirous of catering for themselves.'1

Rowton House, Whitechapel, opened in August 1902. Designed by Harry B. Measures, FRIBA, it was the fifth of six Rowton Houses to be built in the capital between 1892 and 1905, and the first lit by electricity. Since converted to flats, it is now known as Tower House.

https://www.royalholloway.ac.uk/history/research/researchprojects/athomeinthei nstitution/athomeintheinstitution.aspx

http://www.geffrye-museum.org.uk/whatson/exhibitions-and- displays/gallery-2009/Default.aspx?id=29536&page=3

-

Press clipping from unidentified local newspaper, August 1902 (Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives). ↩

Tower House (former Rowton House), 81 Fieldgate Street

Contributed by Rebecca Preston on Sept. 18, 2018

With its distinctive roofline and seven storeys rising sixty feet above ground level, Tower House is a local landmark and towered above its neighbours when first built. Initially called Rowton House, Whitechapel, the building opened in August 1902 and was the fifth of six ‘Rowton Houses’ established in London between 1892 and 1905 to provide decent, low-cost accommodation for single working men. Known as Tower House from 1961, during the late 1970s the building was found to be inadequate as housing and began to decline; in 1983 it was acquired by the Greater London Council on behalf of Tower Hamlets Council. After various schemes to adapt it for use as a public building and supported housing fell through, Tower House was sold to a developer and converted to upmarket apartments in 2005–8.

Rowton Houses in London: ‘Hotels for Working Men’

Rowton Houses were large model lodging houses founded by Montagu (‘Monty’) Lowry Corry, later Lord Rowton (1838–1903), Tory politician, nephew of the seventh Earl of Shaftesbury, and former secretary to the Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli. Known as ‘hotels for working men’, they were a response to the capital’s housing crisis of the 1880s, intended as superior alternatives to the common lodging house, where the poorest Londoners slept in dormitories over a shared kitchen.1 Like other kinds of model housing, Rowton Houses were intended to be models of hygiene and order, and as models for other organisations to follow. Rather than being purely charitable institutions, they were designed to turn a modest profit for shareholders, on the model of five percent or ‘remunerative’ philanthropy. The local and national press, and medical, architectural, sanitary, and municipal journals were broadly supportive of the Houses’ improving aims and reported on them at length, usually from information and images supplied by the company which built them.2

Rowton Houses were not intended to be the cheapest lodgings. Common lodging houses cost from around 4d per night in London at this time and the London County Council (LCC) initially charged 5d at its municipal lodging house. Rowton Houses insisted that their enterprises were not charitable or philanthropic organisations but poor men’s clubs or hotels.3 At the opening of the Whitechapel House, the chairman, Richard Farrant, was reported as saying privately that ‘the Carlton and Reform Clubs might have superior upholstery but that there was not a club in London where a man could live so comfortably, economically, and healthily as at the Rowton Houses’.4 The press made frequent approving comparisons with gentlemen’s clubs and, in many ways, including the exclusion of women, the suites of dayrooms and the encouragement of male sociability, Rowton Houses did resemble all-male elite clubs.5 This was not just a means of differentiating from the competition. In 1899 the company had successfully challenged the LCC in the South Western Police Court over the latter’s claim that Rowton Houses were common lodging houses rather than poor men’s hotels, thus exempting them from the inspection and regulation required of common lodging houses.6

At Rowton House, Whitechapel, 6d bought a clean bed for the night (or 3s 6d for a weekly ticket), access to cooking facilities or cheap meals, washing facilities, barber’s, tailor’s and shoemaker’s shops, lockers, and to suites of day rooms for recreation and rest. One reporter described the House ‘as almost a little township in itself’.7 As was summarised at the opening in 1902, ‘the primary conception has been adhered to of giving each man a separate cubicle with a separate window under his control; and such privacy and such a bed that, in the words of Lord Rowton, an Archbishop might sleep there in decency in comfort’.8

As the nephew of Shaftesbury, Rowton was familiar with experimental model housing schemes around the country. Shaftesbury, and later his son Evelyn Ashley, were presidents of the Society for Improving the Condition of the Labouring Classes, and Rowton attended the opening of this Society’s new men’s lodging house, Shaftesbury Chambers, off Drury Lane, in 1892.9 Shaftesbury and his sons Evelyn and Cecil were also involved with the Artizans’, Labourers’ & General Dwellings Company Ltd (ALGDC) in its early years, which, under the chairmanship and direction of Farrant, had become the largest model dwellings company by 1895.10

In about 1890, Rowton had surveyed conditions in common lodging houses in the East End for the Guinness Trust, newly founded by Edward Cecil Guinness (later Lord Iveagh), and of which Rowton was the first Chairman. As a result, Rowton is said to have pondered the idea of his own scheme of improved lodgings for working men.11 Early in 1890 he wrote to the LCC to ask whether the Council would sell about a third of an acre in the Shelton Street, St Giles, clearance scheme near Drury Lane for the erection of a common lodging house.12 The LCC was planning its own model municipal lodging house, which opened in 1893 on Parker Street as part of the Shelton Street scheme. Rowton’s plan evidently came to nothing and at some point he was introduced by his cousin, Cecil Ashley, to Farrant.13 Deciding that what was needed was a hotel for the working man, of a size that would allow a charge of 6d per night, Rowton, in consultation with Farrant, invested £30,000 in a trial scheme and the first Rowton House opened at Vauxhall in December 1892.14 This was provided initially with 470 cubicles and was built by the ALGDC to the designs of Beeston and Burmester. It proved a success and in 1894 Rowton Houses Limited was formed to build further Houses.15 Rowton was appointed Chairman, the other founding directors being Cecil Ashley, Richard Farrant and Walter Long, MP and former Chairman of the Local Government Board; after accepting a Cabinet post, Long was replaced by William Morris (junior), a partner in the firm of Ashurst Morris Crisp, which acted as the company’s solicitors.

Rowton House, King’s Cross, opened in 1896 (677 cubicles), Newington Butts in 1897 (805 cubicles initially), Hammersmith in 1899 (800 cubicles), Whitechapel in 1902 (816 cubicles) and Camden Town (Arlington House) in 1905 (1087). The architect for all the Houses apart from Vauxhall was Harry Bell Measures, whose characteristic red-brick blocks lined witslit windows, leavened with gables, turrets and terracotta detailing, created a new and easily recognisable style of building in the capital. Of the five London Rowton Houses designed by Measures, only Tower House and Arlington House survive and only Arlington remains in use as a hostel.

The acquisition of the site

Rowton House, Whitechapel, was built on a plot of land belonging to the London Hospital on the north side of Fieldgate Street (formerly Charlotte Street), which corresponds with much of two parcels laid out in 1789–92 with two-storey houses by Thomas Barnes on Charlotte Street and Charlotte Court, which lay behind.16 It is not clear how this location was decided upon but Rowton Houses and its associated companies would have been on the lookout for available plots of building land. Alternatively, it could have been suggested by the London Hospital’s Surveyor, Rowland Plumbe, whom Farrant would have known through his work for the ALGDC.17

Although Charlotte Court’s living conditions were condemned in the 1880s,18 Rowton Houses were not, unlike the LCC municipal lodging houses, built upon areas that had been notorious for their common lodging houses and nor were they intended to provide an alternative to the poorest lodgings. It was reported in 1876 that one fifteenth of the population of the Whitechapel district slept in registered common lodging houses, of which there were 167 that year (eighty-six in 1894 and seventy-six in 1899).19 But the majority of these lay in the northern and southern parts of the Parish of Whitechapel or just beyond, and there were none in Fieldgate Street, before or after the north side was cleared. As noted above, Rowton Houses were intended as poor men’s hotels, and the company chose sites that were served with good transport links as well as centres of work, and stressed that the Whitechapel House was near St Mary’s Station, Whitechapel Road.

By early 1897 the company was in discussion with the London Hospital for the Fieldgate Street site and on 1 March Rowton Houses offered £250 for the lease. Later that month, the Hospital agreed that a Rowton House on the estate would be desirable but required a minimum offer of £300. This was agreed, the ‘public way of Charlotte Court to be eradicated to allow site to be let as one’. Two years later it was confirmed that the company was to be given a 999-year lease, that Lord Rowton was to pay £323 rent, and, in October 1899, Rowland Plumbe reported that the lease was £10,767 for 28,171 ft.20

The site was derelict in May 1899, and Harry Measures gave notice to certify plans of the ‘old buildings’ on the site during August.21 By the end of the year this property had gone, the Medical Officer for Health reporting to the Whitechapel Board of Works that forty-two houses in Charlotte Court and twenty-six houses in Fieldgate Street belonging to the London Hospital had been demolished for ‘Lord Rowton’s scheme’, thereby displacing 432 people.22 According to newspaper reports, some of these were induced ‘with the greatest difficulty to give up possession of their very undesirable residences’, which were padlocked to prevent return prior to demolition.23 In addition to the displacements, there were concerns locally that a Rowton House would draw in large numbers of people from other parts of London.24 Building began in April 1900 and by early April 1901 work on the roof had begun, and the doors opened to lodgers in the middle of August 1902.25 The site reportedly cost more than the others and, as the building had ‘been more costly, and the assessment is very high’, it was stated in 1903 that the charge was to be raised to 8d from 6d per night.26 The LCC Housing Committee reported that the charge at all Rowton Houses had been raised during 1903 to 7d for lodgers staying for one night only but remained at 6d for regulars, until around 1906 when all tickets were said to cost 7d.27

The building and its architect

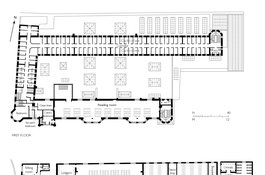

The company described the building as consisting of two adjoining parallelograms, the larger of which, facing Fieldgate Street, had ‘a frontage of 75 feet and a depth of 67 feet, the total superficial area being 29,500 feet’. These were separated by an inner courtyard 50 feet in width and open at one end, in order to provide good air circulation and light. The roofs to the front elevations were covered in green slates, on a concrete-clad steel construction, the remainder being flat and tarmacked.28 The elevations are in pressed Leicester facing bricks, with Fletton bricks on inward faces. Semi-circular windows face outwards from the dayrooms on the first two floors, including in the two bays at this level (one of which has been replaced by the new entrance), and above these are the rows of narrow windows to the hundreds of cubicles, the sashes and frames to which have been replaced throughout the building. Externally, the expanse of brick is relieved with gables, turrets and pink terracotta dressings, and the large projecting porch, flanked with octagonal finials, and which served as the original entrance, is also of terracotta. The diminutive cherub presently seated on the central finial is a recent addition; twentieth-century photographs, and similar designs at other surviving Rowton Houses, indicate that this replaced a larger figure of a child holding a globe on his shoulders, which may have represented a young Atlas.29

Originally the first two floors (known as the ‘entrance floor’ and, above that, the ‘ground floor’) contained the office, staff quarters, and the lodgers’ kitchen, dining and other dayrooms, washing facilities, lockers and services; above these were five floors of cubicles, whose rows of narrow windows contributed to the building’s outwardly institutional appearance. When Measures was asked why he didn’t group his windows, he replied that ‘if I yield to that temptation, then the sleeper has to pay the penalty for the sake of my elevation. Personally, I think the sleeper comes first and that my elevations should truthfully proclaim it’.30 Despite the new entrance and alterations to the windows made as part of the 2005–8 conversion, the Fieldgate Street elevation still reads as a Rowton House, the major alterations to the exterior being the penthouse floor and at the rear of the building.

Fireproofing and infection control

Unsurprisingly for a large institutional building, much was made of the steps taken to render it fireproof. The ground floors were concrete, either laid with solid oak or with cement and granite chippings in the more utilitarian areas.31 On the cubicle floors, floorboards were nailed directly onto concrete so as to avoid a cavity. The cubicles were approached by fireproof staircases, located at the ends of the corridors in the towers, so that lodgers could not be trapped by fire, and each floor was divided by walls into ten sections, to check the spread of a fire horizontally.32 Infection control was to be achieved by the same means, so that each block of cubicles could be closed and fumigated following a suspected outbreak, while the absence of cavities would safeguard against the spread of vermin. There were also fumigating rooms for clothing and bedding on the lower ground floor.

To illustrate the House’s safety, it was claimed, perhaps apocryphally, that a lodger who was determined to start fires in order to claim his reward for raising the alarm failed five times to do so in 1902.33 In addition to using fireproof materials many extinguishers were provided. When Wonderland burned down in the Whitechapel Road in 1911, the staff of Rowton House, which overlooked Wonderland and the East London Picture Palace to its rear, were able to direct eight hoses onto the flames before the fire brigade arrived.34

Whitechapel was the first Rowton House to be fitted with electric light, with local control of the lights on each floor and central control from the office on the ground floor. Also new were the speaking tubes which connected between the office and each floor.

The Municipal Journal was impressed with the progress of Rowton Houses, writing at the time of its opening that Whitechapel ‘is the most palatial of all. Externally a little more ornamentation has been introduced, and the latest building can almost be described as a handsome structure. It is situated in a very typical area of Whitechapel, and the lines of elevation stand out conspicuously from the dirty and squalid rows of surrounding houses’.35

Harry Bell Measures

Harry Bell Measures (1862–1940) was born in Richmond, Surrey, and was articled to Arthur Loader of Brighton in 1877–79, and remained with him as an assistant from 1879 to 1883. At the same time, from 1877 to 1882, he was a student at Brighton School of Science and Art, gaining an honorary medal in Building Construction and the Ashbury Silver Medal in Architectural Design. Measures commenced practice in 1883 with the builder William Willett, designing houses and stabling on the Gunter Estate at Harrington Gardens, Kensington, and laying out roads and houses on the Cadogan Estate in Chelsea.36 Many of these were in red brick with terracotta details and the gables, turrets and other flourishes that would be used more sparingly in his later institutional buildings.

From 1891 until 1901, Measures was architect to the Artizans’, Labourers’ & General Dwellings Company, designing block buildings in Clerkenwell and laying out houses and shops on the Leigham Court Estate, Streatham. In 1893 he became the architect for Rowton Houses and also, in 1893–95, for the Middle Class Dwellings Company, for which he designed Gordon Mansions on the Bedford Estate. Prior to this Beeston and Burmester had served as the two companies’ architects, which were linked to the ALGDC and all run from 16 Great George Street, Westminster.37 Also registered at this address were the Great George Street Chambers Company, the Wharncliffe Dwellings Company, the London Central Railway, and companies set up to run various electrification projects. Farrant, and fellow Rowton Houses director, William Morris junior, appear to have been the principal links between these enterprises, which shared the same directors, secretaries and solicitors;38 Harry Measures and George J. Earle acted as their architect and surveyor, including for Rowton House, Whitechapel.

Rowton Houses and the other companies at 16 Great George Street, Westminster

Building materials were bought in bulk from the same suppliers for the various schemes. For example, the terracotta and glazed bricks and tiles that are such a feature of Measures’ work, including Rowton Houses and the mansion blocks, were bought in huge quantities from J. C. Edwards of Ruabon in Wales.39 Ruabon also supplied the tiles for Measures’ stations for the London Central Railway.40

The Central London Railway (CLR) was first proposed in 1890 by a consortium working through the solicitors Ashurst, Morris, Crisp and Company.41 In 1897 Measures was appointed architect for the station superstructures along what was later known as the Central Line. The following year the CLR Company decided to build single-storey structures only in the first place, so the idea of housing the company’s offices over the Oxford Circus Station was postponed. That project finally went ahead in 1903–4, again to Measures’ design (some authorities have mistakenly attributed the superstructure to Delissa Joseph) and acted for a while as the company’s headquarters.42 It seems Farrant supervised the purchase of materials and the contracts for the railway and presumably the other companies, and that Morris was involved in the layout of the new stations.43

Rowton Houses did not use contractors for its buildings and managed all the building and joinery in-house, overseen by G. J. Earle, the company surveyor, from 1894. To facilitate this, the company had a works at Pimlico Wharf, which it shared with the wider group of businesses, and which Rowton Houses later bought. Middle Class Dwellings Company bills indicate that Rowton Houses and the other companies including the Central London Railway also engaged the same services and suppliers, for instance French polishers and military uniform specialists, presumably allowing savings across the different schemes.44 Savings were also made by centralising some of the services within Rowton Houses and in the early twentieth century, possibly as a result of the smallpox outbreak in 1902, a steam laundry was built at the Newington Butts House to clean all the Rowtons’ linen.45

Lord Rowton was reported as saying at the opening of the Whitechapel House in 1902 that he wished to see the Rowton system applied to barracks, and believed he had support.46 Less than two years later, in May 1904, Measures was appointed Director of Barrack Construction for the War Office, a post which allowed him to build upon his ‘great experience of designing buildings for large numbers of men’.47 Partly due to their similar functional requirements, Measures’ barrack and other military buildings shared many similarities with Rowton Houses, including their U-shaped plans, as seen at the Redford Barracks, Edinburgh. Other examples of Measures’ barrack construction on the lines of Rowton Houses could be seen in his married soldiers’ accommodation at Woolwich.48 But even in these utilitarian buildings Measures was allowed a few of his trademark flourishes. He was given freer rein at the Union Jack Club, Waterloo Road, in Lambeth (1904–7), founded with the assistance of William Morris junior, and on which Measures was honorary architect. Here the day rooms and furniture and fittings resembled those at Rowton Houses.49 Outside, the Club’s entrance was very similar to that at Rowton House, Whitechapel, and near identical to that at the Birmingham Rowton House (opened in 1905). In turn, the entrance of the last London Rowton House, at Camden Town, was almost identical to that at Fieldgate Street. Within, glazed tiles and brickwork were decorative, hard-wearing and hygienic and used across Rowton House interiors. With their turnstiles, ticket offices and tiling, the design of Rowton House entrances bears strong resemblance to Measures’ Central London Railway ticket halls.

Rowton Houses were of course particularly influential in the design of model lodging accommodation in Britain and abroad. Despite the difficult relationship in 1899 during the dispute over whether Rowton Houses were hotels or common lodging houses, an article on the second LCC lodging house, at Deptford, claimed that this was ‘carried out very much on the lines of the Rowton Houses’; it also said that the LCC Housing Committee’s report acknowledged ‘the help they had received in the preparation of the scheme by Lord Rowton and Sir Richard Farrant’.50 The design and organisation of Iveagh House, Dublin, erected in 1905 by the Guinness Trust, also followed that of Rowton Houses, as did the Ada Lewis Women’s Lodging House, opened in London in 1913.51 As Farrant put it in 1904, ‘From almost every capital in Europe inquiries have been made as to the Rowton Houses scheme. Many of the large provincial towns have houses more or less after the design of the London houses’.52

Less often discussed in Rowton Houses’ publicity was the influence of earlier model lodging schemes. There were brief (and apparently undocumented) reports of Rowton’s survey of East End lodging accommodation for the Guinness Trust, and mention of a trip to see a model tenement in Glasgow in the early 1890s, but otherwise little was said about influences.53 The Victoria Homes for Working Men in Whitechapel, built in 1887 and 1891, were however cited as influential precursors to Rowton Houses. Rowton would probably have included the Victoria Home, Commercial Road, in his lodging-house survey of c.1890. In 1897, Augustus Wilké, the manager, told a reporter that both Lord Rowton and the LCC had visited the Victoria Homes, ‘and had come to him for information as to his methods’.54 In an interview of around the same time, Wilké maintained that Rowton got many of his ideas from the Homes, and had improved on them in structure and equipment because Rowton Houses catered for a different class of men. He acknowledged, however, that they were different because, unlike at the Victoria Homes, ‘no personal or religious influence [was] brought to bear on the occupants’.55 He also expressed concern that the presence of the new Whitechapel Rowton House would adversely affect occupancy of the Victoria Homes:

Lord Rowton has in fact attacked one aspect of the housing question, and the Victoria Homes the “dosser” question. Still their spheres of action overlap to some extent and it is a great trouble to Mr Wilké at the present time that Lord Rowton has acquired a large site off the Whitechapel Road nearly opposite Victoria No. 2. It is their Cubicle 6d customers who will be most likely to be drawn away from them, and Mr Wilké is already thinking of the possibility of lowering their charge.56

The day rooms and facilities on the entrance and (upper) ground floor

On entering Rowton House, Whitechapel, lodgers bought a ticket at the office window and, if they wished, weekly lodgers could pay a 6d deposit for a locker, before passing through a turnstile and into a vestibule. From here, lodgers could go up a flight of stairs to a small ‘glass-roofed lounge with palms and flowers’.57 Or they could enter the main corridor, on the lower ground ‘entrance floor’, which ran east-west through the building. The lockers, and the sinks, baths and footbaths (free), baths (1d including soap and towel) and facilities for washing and drying clothes, were all located on the east side of this floor. The tailor, shoemender and barber were in the same area. Once clean and dressed, the men could go to their cubicle for the night or make use of the dining and recreation rooms up to a certain time in the evening.

The dining and smoking rooms

A huge dining room occupied the centre of the entrance floor, with a floor space of 5,891 ft and seating at teak tables for 456 men.58 Lodgers could cook their own suppers over a range, either with food they brought with them or from ingredients bought at the shop. Alternatively, they could buy a cooked meal at prices which, as the company stressed, amounted to little above cost, achieved through the bulk buying of provisions for the five Houses. Lodgers could purchase a pint of tea in a special Rowton House-emblazoned mug for a penny in 1906, while 5d bought a plate of roast mutton or beef with seasonal vegetables followed by a hot pudding.59 Top-lit and ventilated with lantern lights, the dining room was finished with the same ‘high dado of glazed brickwork in tints of cream and chocolate’, as found throughout the dayrooms.60 Due to the size and function of the building, institutional associations were impossible to escape but the aim was to mitigate this through dayroom arrangements and decoration and, at Fieldgate Street, to ‘give an effect of sprightliness and comfort’.61 Framed pictures hung on the walls, the plastering ‘tinted to a shade of terracotta’ above the tiling.62 While Measures was responsible for the design of the building, Rowton and Farrant personally oversaw the interior design and decoration, choosing the bedding, furniture, pictures and, even, at King’s Cross, a stag’s head shot by Rowton, for the walls.63

On the south side of the corridor on the entrance floor lay the smaller smoking room, its windows in the central bays looking, through the railings, into Fieldgate Street. This had space for 140 lodgers at teak tables with additional easy chairs around the fire places at each end. Cards and games of chance which might encourage gambling were banned but chess and draughts were provided.

The Reading Room and its painted panels of The Seasons

The reading room lay immediately above the smoking room on what was known as the (upper) ground floor. This was fitted with cupboards for newspapers and bookcases, from which lodgers could borrow books on application to the Superintendent, open bookcases having been abandoned across the Houses after thefts made it necessary to lock them.

A series of panels ‘emblematic of “the Seasons”’ hung in the reading room. These took up a large part of the back wall facing the windows onto Fieldgate Street, fitted above the tiling. As was widely reported, these were ‘painted by Mr H. F. Strachey of Clutton, near Bristol, and given by him as the practical interest of an artist in the elevating work of a Rowton House’.64 ‘Each season is represented by a single figure and also by a larger composition, while over the fireplace in the middle is a small allegorical work. In it a symbolical figure of England sits enthroned, while the fruits of the land are brought to her by the cultivators’.65

A cousin of Lytton, Henry (Harry) Strachey (1863–1940) studied at the Slade School of Art and was art critic of The Spectator. There were no panels in the other Rowton Houses and it is not known what happened to those at Fieldgate Street. Similar in theme and style are Strachey’s five large panels, of painted canvas, representing scenes of country life, that hang in the picture hall (formerly the refreshment house) at Brockwell Hall, placed there shortly after it was opened to the public as Brockwell Park.66 These were presented to the LCC in 1896 by Harry’s brother, John St Loe Strachey, editor of The Spectator.67 It is likely that Rowton already knew St John Loe Strachey, and both Stracheys attended the lunch at the opening of the Fieldgate Street House in August 1902.68 It is possible that the panels were lost during alterations of 1953, which divided the Reading Room into a Billiard Room and a Quiet Room.69

The ‘open-air lounge’

Near the reading room was a door to the open-air or smoking lounge. As at the previous Rowton Houses, this was formed on the roofs of the rooms below, in this case the kitchen, dining and washroom areas. Invisible from the street, this space, in the void which allowed air and light to circulate within the building, was fifty feet wide and surrounded on three sides by the cubicle floors. Benches were placed around the lantern lights and it was laid out with tubs of flowers as a roof garden.70 Like the decoration, pictures and pot plants within the House, the garden was an attempt by the company to ‘de- institutionalise’ the buildings.71

Cubicle floors

Rowton Houses prided themselves on the superior size and construction of their cubicles and on the quality of the beds and bedding. After experiments with shared dormitories at Vauxhall proved unpopular, all subsequent Houses were provided with individual sleeping cubicles. These measured 5 ft by 7 ft 6 inches and were 9 ft high.72 Each lodger had a sash window under his own control, an iron bedstead with a sprung mattress, a clothes hook, and a chair. The partitions (of strong pine, rather than iron as in shelters and some model lodging houses) reached nearly to the ceiling, with a space at the top. Initially this was left open but in the early twentieth century was meshed in after ‘fishing’ by residents into neighbouring cubicles showed that valuables were unsafe.73 By this means visual privacy was achieved while ensuring the building remained light and well ventilated.

Staff, lodgers and visitors

After problems with staff retention and keeping order in the Vauxhall House, Farrant suggested that the company employ sergeant-majors or quarter-master sergeants from the Army as superintendents, since they were familiar with dealing with large groups of men and could hire from their former ranks. This was agreed and subsequently Rowton Houses relied on them to manage the buildings and their inmates.74 The first Superintendent at Fieldgate Street was Joseph Henry Brownlow, formerly Squadron Sergeant Major in the 10th Royal Hussars. Prior to this he had been the Superintendent at Vauxhall. He died in 1908 and was replaced by another ex-Squadron Sergeant from the regiment, Thomas Webber Bond and his wife Josephine, who were described respectively on the 1911 census as ‘Army Pensioner, Superintendent’ and ‘Lady Superintendent’.75 The other resident staff comprised a restaurant manageress, cook, two waitresses and two maids who looked after the kitchen and dining areas, with a head day porter, four day porters and one night porter to serve the rest of the building.76 And in order to keep the 1,044 separate windows and skylights sparkling, a window cleaner also lived in.77 The two-storey Superintendent’s quarters (two bedrooms, bathroom, WC and kitchen) were reached from just inside the main entrance, near the clerk’s office, over which was his bedroom. The other staff bedrooms lay behind these, ranged in a line along the west side of the building.

The armies of women required to strip and remake the beds each day did not sleep in but had their own rooms in the basement. These had a separate staircase to the cubicle floors, which were closed to lodgers in the daytime, and which did not connect with any of the day rooms or corridors used by the men, so that the lodgers and women never met.78 Clean and soiled linen were also kept separate, thus ensuring that high standards of hygiene as well as morals were upheld.

Unexecuted plans for a Rowton House for Women

A women’s Rowton House had been discussed as early as 1892 and in 1899 ‘an American gentleman’ was said to have offered Rowton a large sum for the purpose but Farrant did not think it could pay.79 ‘The great difficulty’, Farrant was reported as saying at the opening of the Whitechapel House, was ‘the selection of the applicants’, since ‘all comers who can pay and who are not obviously bad characters are admitted to the Rowton houses in the case of men. Such a course would be quite impossible for women’. Nevertheless, he believed that ‘we shall have houses for working girls and women which will compare with the Rowton Houses’.80 Until about 1904 it was stated periodically that the company was still looking for suitable sites, mentioning Hackney in this respect, but the project must have been abandoned. The Society for Improving the Conditions of the Labouring Classes had tried and failed to run a women’s model lodging house in Hatton Garden in 1850–55.81 In 1905 the Society’s architects Davis & Emanuel drew up plans for the LCC for a small ‘women’s common lodging house’ on Parker Street, off Drury Lane, but this did not proceed.82 The Victoria Homes had been considering a home for women on a piece of land near its Whitechapel Road site in the late 1890s but it seems this came to nothing.83 At around the same time, the LCC was also considering the desirability of a women’s municipal lodging house, but all the proposals, including one on a site near Blackfriars Road, Southwark, fell through.84 In 1913, the Ada Lewis Women’s Lodging House, a ‘Hotel for Working Women and Girls’, opened in 1913 on the Old Kent Road.85 This was designed on Rowton House lines by Joseph and Smithem and named for its benefactor, a wealthy Jewish philanthropist.86 Although there were only 220 beds at Ada Lewis House, which initially cost 6d a night, the building ‘was the first hostel on anything like the scale or plan of the working-class men’s lodging houses’.87

Lodgers at Rowton House, Whitechapel

Rowton Houses only made a profit if the cubicles were occupied every night. From at least 1903, it was claimed that the majority of lodgers at Fieldgate Street were ‘regulars’, meaning that they were known to the Superintendent, paid for a weekly ticket and retained the same cubicle. But the House was oversubscribed and ‘a number of permanent lodgers’ were ‘elbowed out from time to time by casuals’. According to this account, casuals were ‘not so cleanly’ as permanent lodgers ‘and it would be impossible to pay the dividend’ if the company had to depend on them. It also claimed the casuals were responsible for the ‘serious’ amount of petty pilfering.88 In 1903, as a result of the smallpox epidemic, the doors were closed to newcomers, and consequently a dividend of only three per cent was declared.89 According to the company historian, the outbreak ‘nearly closed Rowton Houses’, even though the doors were barred only to casual lodgers and the long-term residents were allowed to stay.90 In other words, it seems that casual lodgers were necessary to the profitability of the House and the numbers of ‘respectable’ regulars may have been exaggerated.

The opening of the House in 1902 prompted calls by some local Jews for a specifically Jewish Rowton House to be opened in the area. The Jewish Chronicle was not in favour of this, however, arguing that it would discourage assimilation and that, in any case, Lord Rowton was ‘perfectly willing to receive Jewish lodgers’, and offered them ‘every religious facility they may desire, including the provision of special stoves and utensils’.91 This statement appeared in many local and national papers, which also repeated Rowton’s claim that the chief tailor and bootmaker at Fieldgate Street were Jewish. Others, including Henry Herman Gordon, Progressive councillor and Honorary Secretary of the Poor Jews’ Temporary Shelter on Leman Street, countered that the Whitechapel Rowton House was always full, and that it was not ‘merely a question of “pots and pans”’. Rather, ‘a Jewish Rowton House could be made to serve as “The Alien Immigrants’ Training School”’. According to Gordon, there was ‘a small number, under forty, of nominal Jews’ in Rowton House, Whitechapel, whose Judaism needed strengthening.92

At the time of the census in 1911, the house was very nearly full.93 Of the 804 lodgers, 390 gave their birthplace as Middlesex or London, fifty-eight as Surrey, forty-eight as either Kent or Essex and seventeen came from Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire and Sussex combined. 162 lodgers came from across the rest of England. One man was born at sea and another didn’t know his birthplace. Of the larger clusters born outside England, thirty-six gave their birthplace as Ireland, thirty-one as Scotland, eight as Wales, and fourteen and eleven respectively as Germany and Russia (some of whom, presumably, were Jews). Fifteen lodgers were born in other European countries, and five each in British colonies and the USA. Where stated, most of these men were resident in Britain or naturalised, though a few were visiting. Most were in work, though much of this was menial labour, and a few were pensioners or of private means. Many were employed as labourers at the docks and in warehouses, or in labouring and more skilled jobs associated with shipping, shipbuilding or the sea; others were employed in the building and decorating trades or in connection with the railway. Others again worked in the markets and in food and drink preparation and the provisions and hospitality trades locally; there were also many newspaper vendors, other street sellers and travelling salesmen enumerated. Local occupations, including furniture making and dealing, tailoring, drapery and fur and leatherworking, were all well represented, as were those in printing, the metals trades and engineering, including six engineers. There were also around sixty-five men engaged as clerks, accountants and draughtsmen. Only one journalist was enumerated.94 But, to judge from accounts of the other Houses, the tables in the reading rooms proved very useful to those who wrote for a living, a group which included wrapper- and advertising-card writers and envelope addressers doing low-paid piece work. At least twenty and most probably more of the clerks enumerated in 1911 were ‘advertising’ or ‘addressing’ clerks doing this kind of work for advertising agencies and newspapers. As at the LCC lodging houses and the Victoria Homes locally, this work appears to have been tolerated and even encouraged within the day rooms. More of a nuisance were the ‘begging letter writers’; all kinds of lodging houses were believed to harbour these men but Rowton Houses refused to provide any information to the authorities.95

The youngest lodger, James Watson, a dock labourer born in Bethnal Green, was seventeen years old, and the eldest, Edward Fluery, a married boot and shoemaker born in Ireland, was eighty-five. Most of the men at the Whitechapel Rowton said they were single or widowed, but eighty-six were married.96 Although some clergymen and politicians claimed that the comforts of Rowton Houses would cause men not to marry or to leave their families,97 the married men at Whitechapel may have left the family home temporarily to work in London.

The average numbers of lodgers reportedly declined from around 1907 following a slump in the building trade and lack of work at the docks, and because of a ‘levelling up’ in standards of comparable accommodation.98 At around this time ‘fishing’ over the cubicles became rife and consequently the open space between the top of the cubicle and the ceiling was enclosed with mesh.99 All new building works ceased and the Pimlico Wharf was sold, the joinery, and metal and other workshops eventually moving to Newington Butts. Company policy was to keep improving its Houses, to stay ahead of the other provision being built, but to build no more.100

The decision to build no further Houses must at the very least have also been influenced by the deaths of its founding directors in 1903 and 1906. At Rowton’s death in November 1903, Sir Richard Farrant was elected as the company’s second Chairman. On the death of Farrant three years later, William Morris became Chairman and Company Secretary, and W. T. Dulake took over as managing director.101 Meanwhile Measures had resigned by 1905, following his appointment as Director of Barrack Construction, and Earle remained as surveyor, and to ‘superintend the architectural staff’.102 But, although there was continuity in the business, and an ongoing commitment keep the company profitable, it seems likely that without Rowton, and perhaps especially Farrant, the enterprising drive had gone.

By the end of 1913 lettings were at their highest ever figure and the company dividend restored to 4½ percent, before war intervened and numbers fell sharply.103

Notable lodgers in the early twentieth century

Unlike some of the other Rowton Houses, Whitechapel does not appear to have had its own poets and nor, to judge from surviving published accounts, were there many jobbing writers among its ranks who wrote of their time in Fieldgate Street, although one journalist was enumerated in the 1911 census.104 The American writer and activist, Jack London, probably stayed in the ‘Monster Doss House’, as he called Tower House in his survey of London poverty made in 1902, published a year later as The People of the Abyss. London was not impressed, writing of the ‘uninhabitableness’ of the poor men’s hotels, and their lack of privacy. His account was illustrated with a photograph of Tower House taken from the East before that section of the street had been rebuilt.105

Edward Henry Vizatelly, journalist and son of the co-founder of the Illustrated London News, was removed from the House to the Whitechapel Infirmary, where he died in 1903 from heart failure following pneumonia.106

In late April and early May 1907 several hundred delegates, including Maxim Gorky, Vladimir Lenin, Maxim Litvinov and Josef Stalin, assembled in London for the fifth Congress of the Russian Democratic Labour Party, to discuss the future of the revolutionary movement in Russia. Those arriving at Harwich on the 9 May were reportedly met by Russian spies and British detectives, who accompanied them to Liverpool Street.107 331 delegates attended the conference,108 which was held in the parish hall of the Brotherhood Church in Hackney.109 As Simon Sebag Montefiore notes, some delegates were more equal than others: Gorky, Lenin and those with private incomes stayed in small hotels in Bloomsbury and elsewhere.110 Some were taken in by Russo-Polish immigrants in Whitechapel, or stayed at socialist clubs or hostels locally.111 The press reported that the revolutionaries trooped off to a socialist club in Fulbourne Street and from there took up quarters in various lodging houses.112 According to Helen Rappaport, two of the four non- official delegates, Stalin and Litvinov, stayed for a short time at the Rowton House.113 William J. Fishman claimed they slept in adjoining cubicles for two weeks during the conference.114 Montefiore refers to the ‘legend’ in which Stalin spent his first nights with Litvinov in the Rowton House, where ‘conditions were so dire that Stalin supposedly led a mutiny and got everyone rehoused’.115 They are reported to have resettled at 77 Jubilee Street, ten minutes’ walk east of Fieldgate Street.116 To judge from the short account contained in a memoir written by Konstantin Gandurin, he and other delegates may well have stayed at Rowton House, Whitechapel, in 1907.117

George Orwell is another elusive resident. While it is quite possible that he stayed at Fieldgate Street in his tour of the capital’s lodging houses in the early 1930s, as some accounts claim, the much-quoted passages of Down and Out in Paris and London (1933) do not identify the Rowton Houses he visited. Travelling, probably, from Edmonton Casual Ward, Orwell said that he and his fellow tramp arrived in central London eight hours before the lodging houses opened and so tried, unsuccessfully, to slip into a Rowton House before the doors opened at seven o’clock.118 He noted that they ‘walked up to the magnificent doorway (the Rowton Houses really are magnificent)’, before being turned away.119 At least two hours later they went to a Salvation Army shelter, which could well refer to one of the former Victoria Homes or other Salvation Army shelters locally.120 However this remains uncertain and Arlington House has also been claimed as the Rowton House in which Orwell stayed.

Nevertheless, Orwell was broadly positive about their facilities. Thus, for a shilling, he wrote, 'you get a cubicle to yourself, and the use of excellent bathrooms. You can also pay half a crown for a “special”, which is practically hotel accommodation. The Rowton Houses are splendid buildings, and the only objection to them is the strict discipline, with rules against cooking, card- playing, etc. Perhaps the best advertisement for the Rowton Houses is the fact that they are always full to overflowing. The [LCC] Bruce Houses, at one and a penny, are also excellent.'121

Individuals known to have stayed at Tower House later in the twentieth century include Patrick Nelson, who came to Britain from Kingston, Jamaica, between the wars; electoral registers place him there in 1948.122 In the early 1960s, Nelson, a former model, lover and lifelong friend of Duncan Grant, moved between Tower House and other East End and dockside hostels whilst looking for work, possibly with assistance from the National Labour Board in Stepney.123 He would, presumably, have been one of many more recent and longer-term immigrants staying at Tower House at this time. Nelson moved from Tower House to Arlington House in 1962.124

Visitors

Keen to exclude lodging-house inspectors and those whose intentions smacked of institutional, religious or charitable interference, Rowton Houses Limited welcomed other individuals and organisations into the buildings. A range of local and national dignitaries attended the press view the week before the doors of the Whitechapel House were opened to lodgers. A little later, in February 1904, the Princess of Wales, accompanied by the Bishop of London, was shown over the House by the Superintendent one evening when it was full and returned with the Prince of Wales a few weeks later.125 These ‘surprise’ visits were put to good use by Farrant, who was quoted in approving press reports as saying that ‘the whole place was fit for a lady to go through’.126 Meanwhile official and semi-official delegations from Britain and around the world visited Rowton Houses prior to setting up their own schemes, including at Birmingham, which Harry Measures also designed. In the autumn of 1903 the Rowton directors held a luncheon in the Reading Room at Fieldgate Street for a group of forty delegates from a German Government Commission sent to study the provision of working-class dwellings in England.127

The First World War and after

At least some of the Houses took in Belgian refugees, the Relief Committee paying the company enough to cover overheads, and a little later in the war soldiers were billeted at King’s Cross, Camden Town and Newington Butts. The buildings were never commandeered for hospital or other use, apparently after intervention by William Morris on the grounds that they housed munitions workers. They also served as shelters during air raids and, although no records appear to confirm this, it is likely that Fieldgate Street was used for this purpose.128

Bed occupation reached its highest ever figure after the Armistice and at a census taken by the company in 1921 2,000 out of 5,000 lodgers were unemployed.129 Baedeker still found the Houses ‘clean and not uncomfortable’ in 1923, when they cost a shilling a night or 6s 6d weekly. Some ‘special bedrooms’, which had first been tried at Camden Town, were now also available at Whitechapel and cost 1s 3d a night or 7s 6d weekly.130 These were glazed above the partitions and contained a washstand, a chest of drawers and a mirror.131 Further modernisation took place in 1924.132 Open fires had already been replaced with central heating and the old lodgers’ kitchens and facilities for self-catering were now also removed across the Houses and the catering sections updated.133 Two years later it was claimed in the Daily Mirror that ‘The largest at Camden Town, is called “The Cecil,” “The Ritz” is at Newington Butts; “Claridges” is close to Hammersmith Broadway; and “The Savoy” is in Whitechapel’.134 No doubt this was intended to be humorous but is an indication that Rowton House standards remained higher than comparable accommodation at this date. Neon signs put up on the front of Rowton House, Whitechapel, in 1935 added to its styling as a hotel.135 Despite difficulties in the interwar years when numbers again plummeted, by 1939 the reserve fund stood at £178,000.136

The Second World War and post-war alterations

During the war all six Rowton Houses were used by evacuee children en route to stations for the country.137 13,000 plywood shutters were made for the large numbers of windows and rooflights, and the top floors were evacuated as a precaution. A smattering of remaining men too old to enlist were joined by displaced Poles and Belgians and munitions workers, while the Houses were used as official Rest Centres and unofficially as air-raid shelters, with 350,000 people in total recorded across all six Houses during this time.138 In 1940 the Whitechapel House lost a gable, and the top floor walls were said to be severely damaged.139 Either in the same raid or later in the war the outdoor lounge and skylights were also damaged, and building notices show that repairs to correct this, and to the boundary wall to the north, took place from 1947 through to 1949.140

A Medical Examination Room was created in or shortly after 1948 (by Robert Cromie FRIBA, who was working for the company until around 1953),141 where men were seen by doctors or prior to removal to hospital.142 Further special bedrooms were rolled out from this time and by the 1950s cost 17/6 per week (‘ordinary cubicles’ at 2/6 per night or 16/6 per week).143 ‘Super specials,’ with hot and cold water, now appeared – all in line with Rowton’s original ‘vision of a “hotel” rather than a lodging house, a “club” rather than an institution’.144 However these do not seem to have materialised at Whitechapel until later, suggesting perhaps that its customers tended to be poorer than at the other Houses, and in 1983 ‘super specials’ were found to provide only ‘a fraction of the accommodation’.145

Other updates at Whitechapel in the 1950s under new company architects, Ley, Colbeck and Partners, included showers, a television room on the lower ground floor, and the partition of the reading room to create a separate billiard room.146 Each House had its own darts and billiards team and ‘inter-House matches’ were ‘keenly contested’. Following the attendance of a special meeting in the late 1940s to discuss the new National Health Service, the Rowton House lecture series was begun.147 There were also special lectures on social history and local government organised by the Workers’ Educational Association.148 At each House a number of beds was now reserved for night workers to sleep during the day (as had previously been available at Newington Butts) and also for the National Assistance Board, which preferred to give relief in the form of lodging tickets rather than cash. According to the company history, Rowton Houses were also favoured by magistrates and probation officers for the placement of men.149 The dining rooms, which were now open to non-residents, continued to make only a small profit to keep prices low and served Christmas dinners at a loss, through a bequest to feed the needy once a year.150 At this date it was said that ‘scarcely a week passes without a visit by parties of welfare officers, representatives of Local Authorities, magistrates, housing planners, [and] medical officers’.151

Connections to the founders were maintained through the joint company chairman, Kenneth Dulake, son of the former chairman, and, among the other directors, John Morris, the grandson of William Morris, junior; many of the shareholders also had connections with the earliest investors.152

Tower House and changes to the business after 1961

In 1961 the company took a more major change in direction. Kenneth Dulake announced that ‘the old cubicle room is out of date like the horse and cart’. King’s Cross was to become a £300,000 hotel, and the five other Houses would remain as hostels but were to be upgraded and have their accommodation improved.153 At Whitechapel, the foot baths were removed to enlarge the television room on the lower ground floor and the south wing was converted to bedroom suites, with modifications to the rear windows to accommodate these changes.154 The Tower House name almost certainly dates to these improvements made across the company, and it was observed by the Medical Officer of Health Report for Stepney of 1962 that ‘Tower House (formerly known as “Rowton House”)’ now had 694 beds, rather than 816.155

In 1966 the company changed its name to Rowton Hotels Limited and at some point between this date and 1972 the business was split into hotels and hostels – Whitechapel (and Vauxhall and Camden Town) falling into the latter category. Thus while Rowton Hotels offered cheap hotel accommodation to tourists and travelling salesmen with beds at £2.65 a night, Rowton Hostels now cost 52 pence.156 Tower House was increasingly catering for an older class of lodger with nowhere else to stay and sometimes with addiction and other problems.

In 1963 a resident’s complaint had given the first of many warnings that Tower House presented a fire hazard. This claimed that the gates were continually locked and chained and that the building was ‘a death trap’, and that inspections were useless because notice was always given to the management.157 A report of a meeting between Rowton Houses and the GLC at Tower House in 1976 stated that the house was full, and that any member of the public was admitted as a ‘guest’ provided he had proof of identity and a National Insurance Number.158 This report found the standard of housekeeping to be ‘fairly good’ but that fireproofing and means of escape were still inadequate.159 A statutory notice was served by the GLC under the London Building Act later that year, stipulating the works required to remedy this, and consequently new external stairs and escapes were completed in 1979 and some of the cubicles on the top floor were sealed up.160 Yet in 1982, members of Tower House Residents’ Association repeated the earlier claims regarding locked doors and lack of fire escapes; these, following a site visit, were supported by the GLC, and damning reports began to appear in the national and local press.161 Rowton Houses countered that customers had changed, ‘and not for the better’, and that it could no longer ‘carry out the functions of a public authority’, and offered Tower House and the other hostels to their local authorities.162

A pre-arranged inspection by Tower Hamlets Council on behalf of the health and consumer services committee concluded in early 1983 that ‘The occupiers are not in danger of their safety, welfare or health as a result of the conditions’, and did not recommend a control or compulsory purchase order.163 This was contradicted by another report, made in January 1983 by independent environmental health consultant Mel Cairns on behalf of Tower Hamlets Law Centre and Shelter, as was reported in Parliament. Cairns, who stayed in the building undercover, found Tower House to be overcrowded and unfit for human habitation as defined by the Housing Act 1957, a statutory nuisance under the Public Health Act 1936 and at immediate risk of potentially serious fire. He recommended that the local authority investigate a Compulsory Purchase or Control Order in order to protect the health and safety of the occupiers.164 The report prompted further discussion in the national and local press, which also reported on increasing cases of tuberculosis at Tower House, and that residents wanted a council takeover.165

The Greater London Council took over in November 1983, initially for a period of five years, and proposed a series of improvements including a further reduction of the hostel accommodation to 430, though plans for this work, by Calder, Ashby & Co., surveyors, show a total of 350 beds. After abolition of the GLC in 1986, the building passed to Tower Hamlets Council’s Stepney Neighbourhood, which closed the building in 1989. The housing department then proposed collaborating with housing associations in adapting Tower House for social housing, with small business units in the Vine Court wing (to the north) and the west wing reserved for community use; planning consent was granted in 1990 and a photograph by Isobel Watson of 1992 shows a sign reading ‘Stepney Neighbourhood Annexe’ over the doors of the main entrance.166 As recession deepened, the local papers reported in 1993, a £7m proposal by Stepney Liberals to create a mini town hall in Tower House was shelved.167 A conversion project by a private company mooted in 1994 came to nothing and the building lay empty, by 1998 squatted by homeless people and drug addicts and attracting increasingly lurid headlines.168

Negotiations for the purchase and present conversion began in 1997, initially with the developers Lincoln Holdings PLC and subsequently with an associated company, Greenacre Properties; after several revisions, approval was eventually granted in 2002 for conversion to flats, the works to be completed by August 2008.169 Further permission was granted in May and June 2004 for alterations and additions to the existing building to provide 135 apartments and details were submitted in 2005.170 The conversion, by Brooks Murray Architects, also includes car parking on the lower-ground floor, a roof terrace, and a new entrance in the centre bay of the Fieldgate Street wing, facing Parfett Street. This entrance, with ‘Tower House’ in Art Deco-inspired lettering above, opens into a large new reception area. Outside are two early twentieth-century Gothic octagon-section Stepney Borough pavement bollards. Unlike Tower House, which is unlisted, these are listed Grade II.171

-

This account draws on the project, At Home in the Institution? Asylum, School and Lodging House Interiors in London and South-East England, 1845–1914, led by Jane Hamlett at Royal Holloway, University of London, in 2010–11, and funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (RES-061-25-0389). ↩

-

Jane Hamlett and Rebecca Preston, ‘A Veritable Palace for the Hard- Working Labourer’? Space, Material Culture and Inmate Experience in London’s Rowton Houses, 1892–1918’, in Residential Institutions in Britain, 1725–1970: Inmates & Environments, ed. Jane Hamlett, Lesley Hoskins and Rebecca Preston, 2013, pp.95–100. See also the entry on Rowton Houses on Peter Higginbotham’s Workhouses website: http://www.workhouses.org.uk/Rowton/. ↩

-

E.g. Letter from Richard Farrant to The Times, 5 November 1904, p.9. ↩

-

‘Notes and Comments from Our London Correspondents’, Yorkshire Post, 7 August 1902, p.6. ↩

-

See Jane Hamlett, At Home in the Institution: The Material World of Asylums, Lodging Houses and Schools in Victorian and Edwardian England, 2015, pp.141–3. ↩

-

‘Are Rowton Houses Hotels: Lord Rowton and the LCC’, South London Chronicle, 5 August 1899, p.2. ↩

-

‘Notes and Comments from Our London Correspondents’, The Yorkshire Post, 7 August 1902, p.6. ↩

-

‘Editorial Mems.’, The Sanitary Record and Journal of Sanitary and Municipal Engineering, 14 August 1902, p.159. ↩

-

Society for Improving the Condition of the Labouring Classes Minutes, 4 November 1892, p.130; London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), ACC/3445/SIC/01/012. ↩

-

J. C. Tarn, Five Per Cent Philanthropy: An Account of Housing in Urban Areas between 1840 and 1914, 1973, p.58. ↩

-

Richard Farrant, ‘Lord Rowton and Rowton Houses’, The Cornhill, Vol. 16, 1904, pp. 835–44. ↩

-

London County Council Housing of the Working Classes Committee Minutes, 14 February 1890; LMA, LCC/MIN/07236. ↩

-

Farrant, ‘Lord Rowton and Rowton Houses’, p.835. ↩

-

Ibid., p.836. ↩

-

‘New Model Lodging Houses for London’, The British Architect, 38, 23 December 1892, p.493. ↩

-

Royal London Hospital Archives, RLHLH/F/10/3, Hospital Estate Ledger, ↩

-

During negotiations for the Fieldgate Street site, Plumbe was, with the Bishop of London and the Chief Rabbi, one of the guests invited to inspect the new Rowton House, Newington Butts, in December 1897. See ‘A New Rowton House’, London, 23 December 1897, p.995. ↩

-

Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives (THLHLA), P/BSA/1/5/1/1. ↩

-

Report of the Medical Officer of Health for Whitechapel, 1876, p.10. See also Annual Report of the Medical Officer of Health for Whitechapel, 1894, p.10 and Annual Report of the Medical Officer of Health for Whitechapel, 1899, p.11. There were eighty-four registered common lodging houses (not including free shelters) in the Borough of Stepney in 1902, one sixth of the total in the whole of London. See Report of the Medical Officer of Health for Stepney, 1902, p.19. ↩

-

Estate Sub-Committee Minute Book, 1886–1903, March 1897–October 1899, pp.86–112, Royal London Hospital Archives, RLHLH/A/9/41. ↩

-

LMA, District Surveyors Returns (DSR): serial no: 1899.0316–29; Goad insurance plan, 1899. ↩

-

‘Report by the Medical Officer of Health for the Whitechapel District Board of Works’, Annual Report of the Medical Officer of Health for Whitechapel, 1899, p.21. ↩

-

‘New Rowton House’, Lloyds Weekly Newspaper, 16 October 1898, p.2. ↩

-

‘The School Board Sites: the Hospital’s Explanation’, East London Observer, 25 January 1902, p.6. ↩

-

LMA, DSR serial no: 1900.0205; ‘A New Rowton House for Whitechapel’, East London Observer, 20 April 1901, p.6; ‘A New Rowton House’, London Evening Standard, 7 August 1902, p.7 ↩

-

R. Randall Phillips, ‘Rowton House, Whitechapel, London’, The Brickbuilder, vol. 12, no. 7, July 1903, pp.141–4, p.140. ↩

-

Further Report of the Housing of the Working Classes Committee, Housing of the Working Classes Committee Papers, 25 October 1904, LMA, LCC/MIN/07392; ‘The Work of the Rowton Houses Limited’, Actes du VIIme Congres International des Habitation a Bon Marche, 7–10 August 1906, 1906, appendix: ‘Communications Diverses’, pp.4–5. ↩

-

‘Rowton House’, East London Observer, 9 August 1902, p.8. ↩

-

This figure, just seen in photographs when Rowton House, Whitechapel, was new, was still in place when Isobel Watson photographed the entrance in 1992, but had lost its globe; photographs show that the cherub had also gone by 2001. The cherub at the Birmingham Rowton House, also designed by Measures, has lost its globe but that at Arlington House remains. For a description of the Arlington House entrance porch, and its ‘cherubic yet muscley boy’, see the Historic England List entry by Emily Gee: Arlington House (former Camden Town Rowton House), Number 1396420 https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1396420. ↩

-

H. B. Measures, ‘The Rowton House, Newington Butts’, The British Architect, 22 March 1901, pp.211–14, p.213. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Randall Phillips, ‘Rowton House, Whitechapel’, p.144. ↩

-

‘A Rowton House in Whitechapel’, Pall Mall Gazette, 7 August 1902, p.10. ↩

-

‘“Wonderland” Burned Down’, East London Observer, 19 August 1911, p.7. ↩

-

‘Another Rowton House’, The Municipal Journal, 8 August 1902, p.648. ↩

-

Harry Bell Measures, FRIBA nomination papers, 30 March 1901, RIBA biographical file. His other work for Willetts in the 1880s included houses in Hampstead, Brighton and further houses in Chelsea. ↩

-

Museum of London (MoL), The Middle Class Dwellings Company Limited, Receipt Books, 1888–1896 (4 vols, incomplete run), ephemera collection. This company was renamed Western Mansions Ltd in 1905. ↩

-

See for example, ‘Richard Farrant’, Who’s Who, vol. 52, 1900, Part II, p. 387; The New Hazell Annual and Almanack, Vol. 21, 1906, p. 216; Judy Slinn, Ashurst Morris Crisp: A Radical Firm, 1997, pp.82, 118–19, 121. By 1908 Rowton Houses Limited and some of the other companies were registered at 7 Little College Street, Westminster. ↩

-

MoL, The Middle Class Dwellings Company Limited, Receipt Books, 1888–1896 (4 vols, incomplete run), ephemera collection. ↩

-

J. C. Edwards, Ruabon, Catalogue, 1903, cited in http://tilesoc.org.uk /tile-gazetteer/london.html#r8. ↩

-

Survey of London, _vol. 40, ‘Oxford Street: The Rebuilding of Oxford Street’, The Grosvenor Estate in Mayfair, Part 2 (The Buildings_), _1980, pp.176–84; Slinn, _Ashurst Morris Crisp, pp.118–19. ↩

-

LMA, Acc.1297/CLR1/1, 2; Survey of London, vol. 53: Oxford Street, forthcoming. ↩

-

‘Sudden Death of Sir Richard Farrant’, Pall Mall Gazette, 21 November 1906, p.8; Slinn, Ashurst Morris Crisp, pp.18–19. ↩

-

MoL, The Middle Class Dwellings Company Limited, Receipt Books, 1888–1896 (4 vols, incomplete run), ephemera collection. ↩

-

Sheridan, Rowton Houses, p.89. ↩

-

‘A New Rowton House for London’, Birmingham Daily Gazette, 7 August 1902, p.8. ↩

-

‘The New Barracks at Redford’, The Scotsman, 8 April 1909, p.7. ↩

-

The Survey of London, _Vol. 48: _Woolwich, 2012, p.36. ↩

-

‘The Union Jack Club’, The Graphic, 28 May 1904, p.730. ↩

-

‘LCC Notes’, The British Architect, 20 December 1901, p.473. ↩

-

On Iveagh House, see F. H. A. Aalen, The Iveagh Trust: The first hundred years, 1890–1990, 1990, p.17; the architects were Joseph and Smithem, assisted by Kaye, Parry & Ross, see ibid., p.42. On Rowton Houses’ influence upon Ada Lewis House, which was also designed by Joseph and Smithem, see Memorandum and articles of association for Rowton House and draft scheme for Lodging Houses for Women, Legal papers relating to Mrs Lewis-Hill’s estate, 1910–1920, LMA/4318/B/02/001–3. ↩

-

Farrant, ‘Lord Rowton and Rowton Houses’, p.844. ↩

-

Michael Sheridan, Rowton Houses, 1892–1954, 1956, p.15. ↩

-

‘Working Men’s Homes in Whitechapel’, The British Weekly, 8 April 1897, clipping in London School of Economics (LSE), Booth/B/227, pp.146–64. ↩

-

Printed report of interview with Mr A. Wilkie [sic], general manager, Victoria Homes, Whitechapel Road and Commercial Street, [c.1898]: LSE, Booth/B/227, pp.146–64. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

‘Notes and Comments from Our London Correspondents’, Yorkshire Post, 7 August 1902, p.6. ↩

-

‘Another Rowton House’, Municipal Journal, 8 August 1902, p.648. ↩

-

‘The Work of the Rowton Houses Limited’, Actes du VIIme Congres International des Habitation a Bon Marche, 7–10 August 1906, 1906, appendix: ‘Communications Diverses’, p.4. ↩

-

‘Rowton House’, East London Observer, 9 August 1902, p.8. ↩

-

‘A New Rowton House’, London Evening Standard, 7 August 1902, p.7. ↩

-

‘Rowton House’, East London Observer, 9 August 1902, p.8. ↩

-

Hamlett and Preston, ‘A Veritable Palace’, pp.96–9. ↩

-

Randall Phillips, ‘Rowton House, Whitechapel’, p.144. ↩

-

‘Another Rowton House’, The Municipal Journal, 8 August 1902, p. 648; ‘Rowton House, Fieldgate Street, Whitechapel E’, The Building News, 8 August 1902, p.177. ↩

-

‘Mural Painting’, The Spectator, 30 March 1912, p.11. ↩

-

‘Gift of Paintings for a London Park’, The Times, 28 December 1896, p.7. ↩

-

‘A Rowton House in Whitechapel’, Pall Mall Gazette, 7 August 1902, p.10. ↩

-

Building notice, 28 April 1953, THLHA, Tower Hamlets Building Control file 40664. ↩

-

‘A New Rowton House’, London Evening Standard, 7 August 1902, p.7; ‘Rowton Houses, Limited’, The Lancet, 23 August 1902, p.520. ↩

-

Hamlett and Preston, ‘A Veritable Palace’, pp.100, 101. ↩

-

‘Progress of Rowton Houses’, The Municipal Journal, 22 August 1902, p.691. ↩

-

Sheridan, Rowton Houses, p.43. ↩

-

Ibid., pp.26–7; Jeffery Williams, Byng of Vimy: General and Governor General, 1983, p.19. ↩

-

‘Obituary’, Milngavie and Bearsden Herald, 3 April 1908, p.3; The National Archives (TNA), RG 14/1497 ED 24, 1. ↩

-

TNA, RG 14/1497 ED 24, 1. ↩

-

‘A New Rowton House’, The Times, 7 August 1902, p.3, and ibid. ↩

-

‘Rowton House’, East London Observer, 9 August 1902, p.8. ↩

-

‘Workingmen’s Hotels’, The New York Times, 2 September 1898, p.4. ↩

-

Wigan Observer and District Advertiser, 20 August 1902, p.6. ↩

-

See Hamlett, At Home in the Institution, p.136. ↩

-

Women’s Common Lodging House, 1905, LMA, GLC/AR/BR/22/BA/027856. ↩

-

‘Working Men’s Homes in Whitechapel’, The British Weekly, 8 April 1897, clipping, and printed report of interview with Mr A. Wilkie, general manager, Victoria Homes, Whitechapel Road and Commercial Street, [c.1898] in Booth/B/227, pp.146–64. ↩

-

See Emily Gee, ‘“Where shall she live?”: Housing the New Working Woman in Late Victorian and Edwardian London’, in Living, Leisure and Law: Eight Building Types in England 1800–1941, ed. Geoff Brandwood, 2010, pp.93–5; and https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1386034. ↩

-

Gee, ‘“Where Shall She Live?”’, pp.104–5. ↩

-

Lewis was the widow of the philanthropist, Samuel Lewis, founder of the Samuel Lewis housing Trust, whose architects were Joseph and Smithem; Samuel Lewis left £20,000 to fund an Ada Lewis wing of the London Hospital: Probate copy and printed copy of the will of Samuel Lewis Esq., 1901, LMA/4318/A/01/001/02. ↩

-

Emily Gee, ‘“Where Shall She Live?”: The History and Designation of Housing for Working Women in London 1880–1925’, Journal of Architectural Conservation, No. 2 Vol. 15, July 2009, pp.27–46, p.42. ↩

-

Randall Phillips, ‘Rowton House, Whitechapel’, p.141. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Sheridan, Rowton Houses, p.89. ↩

-

‘A Jewish Rowton House’, The Jewish Chronicle, 20 March 1903, p.20. ↩

-

‘Correspondence: A Jewish Rowton House’, The Jewish Chronicle, 27 March 1903, p.3. ↩

-

TNA, RG 14/1497, ED 24, 2–28. ↩

-

Louis Jeski. A Louis or Lew Jeski also appears at the Whitechapel Rowton House in most electoral registers from 1935 up to 1963: Ancestry.com, London, England, Electoral Registers, 1832–1965. ↩

-

Report of the Departmental Committee on Vagrancy, Vol. II, Digest of evidence, 1906, p.388. ↩

-

TNA, RG 14/1497, ED 24, 2–28. ↩

-

Percy Alden and Edward E. Hayward, Housing, 1907, p.113; Hamlett and Preston, ‘A Veritable Palace’, p.98. ↩

-

Sheridan, Rowton Houses, p.43. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid., p.44. ↩

-

Ibid., pp.42–3. ↩

-

‘Rowton House, Camden Town’, The Builder, 8 December 1905, pp.790–1. ↩

-

Sheridan, Rowton Houses, pp.51–2. ↩

-

For the many accounts written by Rowton lodgers at the turn of the century, including the Rowton House poets, William Andrew Mackenzie and ‘Supertramp’ W. H. Davies, the majority of which told of life at King’s Cross, Newington Butts and Hammersmith, see Hamlett and Preston, ‘A Veritable Palace’. ↩

-

Jack London, _The People of the _Abyss, 1903, pp.240–1. ↩

-

‘Sad End of a Famous War Correspondent’, Inverness Courier, 17 April 1903, p.3 ↩

-

‘Mock Duma in London’, Daily Mirror, 10 May 1907, p.5. ↩

-

Elia Levin, ‘The Social Democratic Party of Russia and Its Recent Congress’, Social Democrat, Vol. XI No. 9 September, 1907, pp.538–46, p.541. ↩

-

Stanley Buder, Visionaries and Planners: The Garden City Movement and the Modern Community, 1990, pp.54-5; ‘Duma Reassembles’, London Daily News, 14 May 1907, p.7. ↩

-

Simon Sebag Montefiore, Young Stalin, 2007, p.146; Helen Rappaport, Conspirator: Lenin in Exile, 2010, p.143. ↩

-

Rappaport, Conspirator, p.143 ↩

-

‘Revolutionists in London’, London Daily News, 9 May 1907, p.8; ‘Mock Duma in London’, Daily Mirror, 10 May 1907, p.5. ↩

-

Rappaport, Conspirator, pp.143–4. ↩

-

William J. Fishman, The Streets of East London, 1979, p.124. According to Edward Ellis Smith, in The Young Stalin, 1968, pp.188–9, Stalin’s accounts of the conference were brief and apparently unconcerned with delegates’ accommodation. ↩

-

Montefiore, Young Stalin, p.146. ↩

-

Ibid.; Rappaport, Conspirator, p.144. ↩

-

Konstantin Gandurin, Epizody podpol’ya, 1934, pp.26–8. ↩

-

George Orwell, Down and Out in Paris and London, 1933, 1963 edn., p.137. For the identification of the anonymised casual wards where Orwell stayed, see http://www.1900s.org.uk/1900s-casual-ward-experiemces.htm. ↩

-

Orwell, Down and Out in Paris and London, pp.137–8. ↩

-

Ibid., p.138. ↩

-

Ibid., p.186. See also Eric Blair, ‘Common Lodging Houses’, The New Statesman, 1932, reprinted in Edward Hyams, Ed, New Statesmanship: An anthology, 1963, pp.86–8. ↩

-

Ancestry.com, London, England, Electoral Registers, 1832–_1965._ ↩

-

Gemma Romain, Race, Sexuality and Identity in Britain and America: The Biography of Patrick Nelson, 1916–1963, 2017, pp.188–93. ↩

-

Ibid., p.189. ↩

-

‘The Princess of Wales visits a Rowton House’, St James’s Gazette, 26 February 1904, p.8. ↩

-

‘Royalty at Rowton House’, London Daily News, 4 March 1904, p.5. ↩

-

Sheridan, Rowton Houses, p.37; East London Observer, 10 October 1903, p.5. ↩

-

Sheridan, Rowton Houses, pp.52–4. ↩

-

Ibid., p.58. ↩

-

Karl Baedeker, London and its Environs: handbook for travellers, 1923, p.57. ↩

-

Undated Rowton Houses ‘Up to London’ booklet, c.1930, n.p., Hammersmith & Fulham Archives. ↩

-

LMA, DSR serial no: 1924.0843. ↩

-

Sheridan, Rowton Houses, p.59. ↩

-

Daily Mirror, 17 June 1926, p.2. ↩

-

Letters from Rowton Houses Ltd to the District Surveyor for Stepney West, 5 March and 1 August 1935, THLHA, Tower Hamlets Building Control file 40664. ↩

-

Sheridan, Rowton Houses, p.65. ↩

-

Ibid., p.68. ↩

-

Ibid., pp.69, 71. ↩

-

Ibid., p.73. ↩

-

Metropolitan Borough of Stepney report to the LCC, 2 September 1947, Rowton Houses in London, 1947–1951, TNA, HLG/101/513; Building Notices, 24 March 1947, 4 September 1948, 12 August 1948, 24 January 1949, THLHA, Tower Hamlets Building Control file 40664. ↩

-

Letter from Robert Cromie to the District Surveyor, 23 June 1949, THLHA, Tower Hamlets Building Control file, 40664. ↩

-

Sheridan, Rowton Houses, p.79. ↩

-

Ibid., pp. 86–7. ↩

-

Ibid., pp.93, 95. ↩

-

M. Cairns, Environmental Health Report, Tower House Hostel, for Tower Hamlets Law Centre, January 1983, p.4, THLHA. ↩

-

Sheridan, Rowton Houses, p.88, 93; Building Notice, 30 April 1953, THLHA Building Control file, 40664. ↩

-

Sheridan, Rowton Houses, pp. 91–2. ↩

-

Ibid., p.92. ↩

-

Ibid., p.87. ↩

-

Ibid., pp.88–9. ↩

-

Ibid., p.87. ↩

-

Ibid., pp.42–3. ↩

-

‘Rowton House becomes £300,000 Hotel’, Daily Telegraph, 16 October 1961, p.15; ‘Empty Beds Led to Hotel Decision’, Daily Telegraph, 11 October 1961, p.22. ↩

-

Letters to LCC Superintending Architect from Ley, Colbeck and Partners, architects, 15 and 26 November and 18 December 1962, THLHA Tower Hamlets Building Control file, 40664. ↩

-

Report of the Medical Officer of Health for Stepney, London, 1962, p.27. ↩

-

Robert Head, ‘Your Money: Tourism is a Victim of War’, Daily Mirror, 15 August 1972, p.20. ↩

-

Letter addressed from Tower House, 57 Fieldgate Street to officer in charge, Albert Embankment (probably the London Fire Brigade), received 22 May 1963, THLHA, Tower Hamlets Building Control file, 40664. ↩

-

Report of a meeting between the GLC and Rowton Houses Ltd., 3 March 1976, THLHA Tower Hamlets Building Control file, 40664. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-