From manure works to tenement dwellings

Contributed by Survey of London on Jan. 3, 2018

Much of the previously undeveloped site that now houses Swanlea School had

fallen to use by the Whitechapel Distillery by the 1840s. This land was sold

to George Torr in 1861 and adapted within a year to be a manure or ‘animal

charcoal’ works, conveniently adjacent to the Whitechapel Coal Depot. Around

the corner from his sheds, Torr built offices and a chimney on Buck’s Row

(Durward Street) employing William Snooke and Henry Stock as architects. Torr

died in 1867, but the manure works continued into the late 1890s having

receded to its northern parts.

The Buck’s Row office that George Torr had built in the 1860s had by 1890 been

adapted for club and library use. The building passed to the Brady Street

Boys’ Club, established through Rothschild philanthropy in 1896 as a Jewish

club, drawing boys largely from the new blocks of dwellings on Brady Street

including those of the Four Percent Industrial Dwellings Society which funded

extension of the club in 1905 in an Arts & Crafts style by Ernest Joseph,

who had a special interest in youth work via the Jewish Lads’ Brigade. The

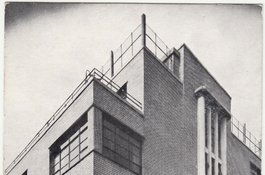

premises were wholly rebuilt in larger and strikingly Modernist form in 1936–8

to plans by Joseph, who had been influenced by Continental refugee architects.

He also designed the Brady Street Girls’ Club & Settlement of 1935 on

Hanbury Street. The area’s Jewish population declined, attitudes to teenagers

changed and in the 1960s the boys’ and girls’ clubs amalgamated on Hanbury

Street. From the 1970s to its demolition around 1990 the former boys’ club

building was used as a Tower Hamlets Council and Department of Health and

Social Security training workshop called Brady House.

Further east, on Torr’s land along the north side of Buck’s Row, a long three-

storey warehouse was built in 1864. Taken by Browne & Eagle for wool

storage, this was the starting point of that firm’s extensive presence across

Whitechapel. Divided into three sections, this warehouse with timber floors on

iron columns was raised two further storeys in 1880–1. An iron boiler house

adjoined to the northeast on Brady Street from 1879 to 1933. Wool storage was

in decline by 1905, and the western division was used by HM Customs and Excise

for a time from 1914. The other sections were used for hops storage from 1924.

Browne & Eagle departed and the warehouse was auctioned off in 1936. It

saw use by Stepney Council before clearance in the 1970s.

The manure works gave way to housing in stages. Brady Street Dwellings were

built by the Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings Company in 1889–90, 286

densely packed flats in twelve four-storey and attic blocks with concrete

floors, designed by N. S. Joseph and Smithem, architects. By the end of the

1890s they were said to be wholly tenanted by Jewish people. This was a major

location of the Stepney Tenants’ Defence League’s successful rent strike of

1938. Brady Street Mansions, adjoining to the north, was a project by

Nathaniel and Ralph Davis via the Great Eastern Railway Company. A scheme of

1898 by H. H. Collins, architect, was partially seen through in 1901, for 120

flats in six blocks, again with concrete floors. Brady Street Mansions were

sold off in 1933 and cleared around 1975. Brady Street Dwellings stood until

about 1980.

Shopping-mall schemes

Contributed by Survey of London on Jan. 4, 2018

From 1972 to 1988 there were plans for a large shopping mall to the north of

Whitechapel Road and Whitechapel Station. These were initiated by the London

Borough of Tower Hamlets, which owned land north of Durward Street and was in

the process of acquiring Greater London Council owned property, and planned

co-operatively with London Transport, which owned most of what lay to the

south of Durward Street. A first scheme incorporated substantial office and

residential elements and proposed building above the railway line. The

factories north of Durward Street and the housing between Durward Street and

Winthrop Street were cleared in the early 1970s, leaving just the coal-drop

viaduct, Rosenbergers and Brady House on Durward Street, Brady Street

Dwellings, and a garage immediately south of the Jewish Burial Ground in

Bethnal Green.

The Shankland Cox Partnership put forward four development options in 1975,

soon reduced to three, ranging in extent from just the east side of

Whitechapel Station to Brady Street, to all the way to Vallance Road in the

west. Redevelopment planning extended well northwards into Spitalfields and

Bethnal Green. Abbott Howard, architects, took forward a preferred scheme

before 1979 when the Council briefed Sam Chippindale Development Services to

prepare a plan for almost fourteen acres ‘loosely based on a Brent

Cross/Arndale theme’; Chippindale, a founder of Arndale, had not previously

been active in London. Through Trip and Wakeham Partnership, architects,

this had become a huge project (larger in fact than Brent’s Cross) extending

to the northern boundary of the parish, intending 800,000 square feet of

retail including six or seven department stores, 300,000 square feet of office

space, flats and parking for 1800 cars and a bus station.

There was perceived competition from Surrey Docks, but all seemed set to go

ahead in 1983. However, two big retailers pulled out and Chippindale, voicing

doubt (the project ‘hadn’t got a cat in hell’s chance of succeeding’), was

sacked in 1985. The scheme’s commercial viability was further questioned, but

concerned at being the only London borough both not to have a large retail

centre and expecting a population increase in the 1980s, the Council issued a

new development brief. Competing proposals included a scheme by Inner City

Enterprises submitted with the Tower Hamlets Environment Trust on behalf of

the Whitechapel Development Trust. This became known as ‘the community plan’;

its architects were CZWG. A more commercial rival (more offices and parking,

less residential) from Pengap Securities Ltd working with Chapman Taylor

Partners was favoured. Pengap was taken over by the Burton Group in 1987 and

the project was passed around, to former Pengap directors as Wingate Property

and Investment, then to Chase Property Holdings and on to Trafalgar House with

Consortium Commercial. The scheme they submitted and gained permission to

build in 1988 would have had a large domical central feature and a nine-storey

tower on Brady Street. It would also have meant clearance of 235–245 and

287–317 Whitechapel Road. But negotiations unravelled and by the end of the

year the project had died, its abandonment said to be connected to proposals

for the Grand Metropolitan owned Albion Brewery site. Meanwhile there had been

vast quantities of fly-tipping on the empty land, to a depth of 2–3m.

What had been the Kearley & Tonge site south of Vallance Gardens was used

for car auctions, as a lorry park and as a Sunday market for second-hand goods

in the 1980s and 90s. A spin-off from Brick Lane’s then gentrifying market,

this was misleadingly referred to as Whitechapel Waste, and more accurately

described as the 'kalo' (Bengali for black) market.

Swanlea School

Contributed by Survey of London on Jan. 4, 2018

After the failure of the shopping-mall schemes in 1988 the fly-tipped land

north of Durward Street and west of the railway and Essex Wharf was tidied up

through a central-government City Challenge grant for use by Tower Hamlets

Council to build a secondary school. This was the first new one anywhere in

London for a decade, and thus the first to be designed around the exigencies

of the National Curriculum introduced in 1988, and so an influential project.

Swanlea School went up in 1991–3, to graceful and innovative designs directly

influenced by Hampshire County Architects, led by Sir Colin Stansfield Smith,

whose reputation for school design was then without equal. Here they were

involved as part of a consortium headed by the Percy Thomas Partnership, with

Ron Morgan as project architect. Leading engineers, YRM Anthony Hunt

Associates (structure) and Whitby & Bird (services), were also engaged.

Monk Construction took the building contract, seen through after a takeover by

Trafalgar House Construction (Regions) Ltd.

To provide for 1050 pupils a central east–west spine is a storeyed corridor

that was conceived as a ‘mall’ with explicit reference to a shopping idiom

from Linda Austin, the school’s first head teacher. This has an S-profile

glazed roof that sweeps over a tubular-steel frame with ‘radiating trusses of

tree-like form’. It connects largely stock-brick-clad classroom blocks,

many separately articulated under serried curved roofs. Beyond a southerly

landscaped garden and on Durward Street there was a freestanding caretaker’s

house (south-west) and an area allocated for community uses (south-east). That

was reconfigured in keeping with the design of the school in 2000–2 as the

Tower Hamlets City Learning Centre, an early example of a government-backed

facility of this type, designed to provide information-technology education

for networks of local schools and businesses. In 2012 Bouygues Ltd with AWW,

architects, addressed ventilation problems in the ‘mall’ and added a three-

storey teaching block to the north, then in 2015 the southerly learning centre

was converted and extended by Tower Hamlets Council’s own architects to be a

dark-stained larch-clad sixth-form centre.

Off the streets and into Brady Boys' Club

Contributed by Denis on June 6, 2017

I was born and grew up on the Whitechapel side of the railway, just off

Vallance road, on a street called Anglesea Street (demolished, now Fakruddin

Street). It was a play street, which they had in those days. The only traffic

was low-level and connected to the railway but it was very rare, so we just

played in the street as kids. Of course nearby there was a lot of bombed-out

houses and bomb sites and we used to play on those too and had great fun.

My father was in the Auxiliary Fire Service during the war and I'm fortunate

to have some excellent photographs of

him in uniform. My

mother was a nurse during wartime.

The last V2 bomb that hit London was in Vallance Road, and my mother told me

that she was changing my nappy when it hit and went outside into the Anderson

Shelter - which probably offered less protection than the house but that's how

it was.

Our house was a two-up-two-down terraced house, toilet in the garden of

course. And also the water supply was also outside, but we were fortunate in

that when you walked out the back of the house it used to drop down and then

there was a step up onto a small area of lawn. My dad used to block up the

drain, turn on the outside tap and we had our own paddling pool.

As I grew up I went to Deal Street School and made some good friends there. We

used to go each other's house and spend time with each other's families. It

was really nice.

When I moved from Deal Street School to Robert Montefiore School, which is in

Vallance Road, my friends and myself used to go walkabouts because we were too

old then to play on the bombsites. That's when my father took an interest. He

realised we were doing nothing other than walking the streets. So one day he

just grabbed me and took me to the Brady Boys’ Club, which was near Brady

Street Buildings or Mansions at that time. There I got interested in

photography and concert party. That got me off the streets.

While I was at Robert Montefiore Secondary School, one of the teachers there

saw that I had a bit of a knack for metal and he got me extra metalwork

lessons. He was known as Mr Hartley, and with his help I managed to get an

apprenticeship at Imperial College at South Kensington and so when I was

fifteen and four months I was now travelling from Whitechapel Station up to

South Kensington every day. I knew that station inside out.

.jpg.265x175_q85_crop-0%2C0.jpg)

_b8iCYCX.jpg.265x175_q85_crop-0%2C0.jpg)