Nagpal House, site of George Yard Ragged School

2006-7 offices with flats above, on site of George Yard Ragged School

George Yard Mission and Ragged School

Contributed by Survey of London on Sept. 12, 2019

The George Yard Mission and Ragged School was one of the earliest sustained endeavours in Whitechapel to address the travails of the poor. Ragged schools to provide free education for destitute children grew out of isolated charitable initiatives, most famously that of John Pounds, a Portsmouth cobbler. Impetus for expansion came through the foundation in 1844 of the Ragged School Union in London, under the patronage of Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury, and with support from Charles Dickens, to provide education for the poorest of the poor, often homeless, such that refuges were an integral part of the endeavour. By 1851 there were more than 100 ragged schools educating 10,000 children.1

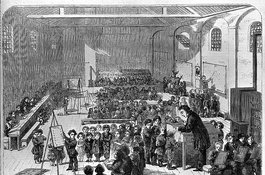

In 1852 Robert Hanbury, senior and junior, of Truman, Hanbury, Buxton & Co., brewers, began fundraising for a ragged school in Whitechapel, under the auspices of the Rev. Hugh Allen of St Jude’s church. But they decided instead to use their site off the east side of Commercial Street for a Boys’ Refuge and Industrial School. The George Yard school was founded in 1854 by George Holland (1824–1900), a grocer in the Minories who devoted the rest of his working life to what became the George Yard Mission and Ragged School. Holland converted a former distillery building of 1836 on the east side of George Yard at the back of 88 Whitechapel High Street. The teaching, at first of just ‘some thirty rough boys’, was conducted initially with pupil-teachers assisting Holland in a single lofty room. It had a markedly more personal and pious tone than that which characterised later efforts led by the Rev. Samuel Barnett from St Jude’s, not just in being avowedly evangelising, but also in a less astringent attitude to charity, which was dispensed with less judgement as to the ‘deserving’ or ‘undeserving’ character of the recipients, most of whom were acutely poor. Holland’s devotion to his task attracted the attention of Shaftesbury, which opened up a world of affluent connections that sustained the Mission into the twentieth century. By 1857 it was said 700 children were under instruction. There was a day school, Sunday school, evening schools, a George Yard Temperance Society, and a marching band. Teaching continued to follow the pupil-teacher method and the Mission provided meals, sometimes accommodation, and trips to the ‘country’, destinations such as Hampstead, Enfield and Addiscombe. In 1861 a ‘shelter for outcast boys’ opened at the top end of George Yard on Wentworth Street. By the 1870s a Lodging House Gospel Mission was visiting nine or ten lodging houses a week.2

With the establishment of Board Schools after 1870, the number of ragged schools diminished from a peak of around 150 to around thirty within a few years, a matter of regret for Shaftesbury who observed that the Board Schools ‘would not feed, clothe and educate in the fear and love of God, the destitute children for whom the Ragged Schools were intended’.3 The George Yard Ragged School and Mission came to concentrate on infant and evening education, and general welfare and evangelical work. The original building was used as the Flowers of the Forest day nursery from 1875 to 1887. Aristocratic patrons paid for three cottages, or ‘Homes for the Weary and the Drooping’, to give short holidays to ‘respectable married women and their infants’ in leafy areas on the edge of London, and the Nonington training school for young women was established in Addiscombe.4

Expansion ensued in the late 1880s with two new buildings in Angel Alley for an infants’ school and a shelter and library, and the adaptation of two others, 87 Whitechapel High Street, which connected at the rear to the old school, now a mission hall, and an adapted building in Angel Alley (84B Whitechapel High Street), the whole group ‘almost puzzling in its labyrinthine variety’.5 By the time of Holland’s death in 1900, the school and mission were said to have seen 60,000 children pass through.6

The George Yard Mission continued for a time under the superintendence of a Col. Hayne, but the LCC found the converted distillery unsuitable for continuing school use in 1905. Closure followed, the children transferring to the new Commercial Street School on the other side of George Yard.7 The building continued as a mission hall, with a floor inserted to create sheltered accommodation in four rooms. As the area’s population grew increasingly Jewish, the location came to seem less than ideal for an overtly Christian organisation. Frederic Alford Snell (1859–1954), Secretary at the mission from 1885 to 1923 noted, ‘it had been overwhelmed with the alien tide and the commercial tide too. They were being nearly smoked out by the Dust Destructor’.8 In 1923 the George Yard Mission merged with the King Edward Institution, another former ragged school, north of Old Montague Street in Spitalfields, and both in turn merged in 1934 with the Good Shepherd Mission in Bethnal Green. All the Whitechapel buildings were sold.9 The distillery–school building was subsequently used as an auction room by D. Stanton & Sons Ltd. Two further floors were inserted in 1934 when 88 Whitechapel High Street, to which the building once again formed an adjunct, was adapted for the Jewish Post, and the ground floor strengthened to take printing presses. It was destroyed in the Second World War and the site cleared and left empty.10

Nagpal House (1 Gunthorpe Street) is a four-storey block of flats with ground-floor offices, built in 2006–7 on the long vacant site of the distillery that was used from 1854 to 1923 as the George Yard Mission and Ragged School. It was built for the owners, S. and B. Nagpal, by Zencroft Developments to designs by Richard Bonshor, architect. The upper storeys project with irregular triangle-plan oriels creating a zig-zag pattern, with windows on the shorter south-facing sides to prevent overlooking of 4 Gunthorpe Street. The ground-floor units are used by solicitors and as a health and beauty clinic.11

-

John Shirley, ‘Ragged and Industrial Schools in England’, Charity Organisation Review, ns vol.9/49, Jan 1901, pp.9–16 ↩

-

Morning Advertiser, 23 June 1852, p.1; 16 Feb 1853, p.4; 15 July 1857, p.1; 9 Nov 1865, p.5: Illustrated London News, 17 Sept 1853, p.239:Illustrated Times, 1 Jan 1859, pp.3–6: East London Observer (ELO), 2 July 1859, p.2; 30 April 1887, p.7: Morning Post, 23 Jan 1861, p.3; 20 March 1874, p.5: Penny Illustrated Paper, 3 Sept 1864, p.146: London Evening Standard, 9 Dec 1869, p.5: ed. Richard Mudie-Smith, The Religious Life of London, 1904, pp.33,52 ↩

-

Norwood News, 5 July 1875, p.3 ↩

-

Croydon Advertiser and Surrey County Reporter, 22 May 1886, p.2: Bedfordshire Mercury, 23 Jan 1875, p.6: ELO, 28 April 1877, p.6; 15 June 1901, p.6 ↩

-

ELO, 30 April 1887, p.7: Tower Hamlets Independent and East End Advertiser, 30 April 1887, p.6: ed. C. S. Loch, The Charities Register and Digest, 1890, pp.483–4: Goad ↩

-

ELO, 25 Aug 1900, p.5: Census: Ancestry:Thomas Paul, ‘Among the Little Waifs of London’, in ed. Arthur T. Pierson,The Miracle of Missions: Modern Marvels in the History of Missionary Enterprise, 1899, pp.148–68 ↩

-

London County Council Minutes, 30 May 1905, p.2082; 13 February 1906, p.247; 27 March 1906, p.823 ↩

-

ELO, 19 May 1923, p.3 ↩

-

Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives (THLHLA), W/GSM/1/5/3: ed. F. H. W. Sheppard, Survey of London: _vol.27,_Spitalfields and Mile End New Town, 1957, pp.265–88: www.goodshepherdmission.org.uk/ ↩

-

Post Office Directories: London Metropolitan Archives, District Surveyors' Returns: The National Archives, IR58/83839/5696: ELO, 26 May 1923, p.2; 4 Dec 1926, p.5 ↩

-

THLHLA, Building Control files 80545, 15859: Tower Hamlets planning applications online ↩

A Visit to a Ragged School - 1859

Contributed by David Charnick on Oct. 23, 2018

A contributor to the _East London Observer _of 2 July 1859 - submitting under the name of A Christian - reported an impromptu visit to the George Yard Ragged School. This extract gives a good idea of the needs that George Holland was trying to address.

The bible lying open before me, pointing to the 6th verse of the 5th chapter of Matthew, 'Blessed be they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness, for they shall be filled' —I asked a very little, pale, thin-faced boy, what our Saviour meant by that? He reflected a moment, and then said, 'Why, sir, I suppose he means that we are blessed on coming out of church on a Sunday morning, when we are hungry and thirsty, and that we shall have something to eat.' I remarked to Mr. Holland that that was a very strange answer, 'Not so, sir,' said he, and calling the boy to him, asked, 'What have you had to eat today?' 'Nothing, sir.' 'Well, my boy, and what did you have yesterday?' 'One slice of bread, teacher,' and the boy's dim eyes filled. 'There, sir,' said Mr. H., 'that will account for the boy's strange answer.' Alas! I saw at once, too plainly, that it did account for the seeming strangeness of his reply. In reply to my questions, Mr Holland informed me that hunger and nothing to eat was the case with a great number of the children, and that he had known them at times fall off the forms to the floor from sheer exhaustion, caused by the want of food. He deplored and lamented the want of funds whereby this pitiable state of things might be remedied. Upon handing the superintendent a trifle to purchase some bread with, a pleased light broke over the countenances of many.

Describing the George Yard Ragged School

Contributed by Survey of London on April 17, 2018

East End historian and guide David Charnick recounts some of the history of the former George Yard Ragged School

"This [site] used to be George Yard and the ragged school was set up as part of the George Yard Mission. Just around the corner on Whitechapel High Street itself at number 87 (which nowadays is Cashino, one of these amusements arcades) is where George Holland set up the base for his mission. It was aimed particularly at this street which was described in the East London Advertiser in 1888 as one of the most dangerous streets in the area because of the crime around here and the prostitution, et cetera.

"This was the site of the actual ragged school itself. You would have the building here which stretched back to the area covered now by the Whitechapel Art Gallery extension. It would be quite a modest building which would be accommodating children who were from very destitute families who couldn’t get places in the general charity schools and hence the name 'ragged schools'. These children would have raggedy clothes and often no shoes or anything like that. They would have been from the local area because this was an area of great poverty in the 19th century.

"The ragged school was established in 1853 as part of the mission. George Holland was a provisions merchant but he had a change of heart and became an evangelist and decided to come east to Whitechapel to administrate a modest outreach.

"It is said that in 1888 with the Ripper murders, the spotlight was turned on the East End and then everyone was realising what was going on here and the poverty, et cetera. In fact, people like George Holland were coming down in the 1850s, so long before the Ripper murders there was an awareness of the problems that were being caused here by the expansion of London.

"The ragged school was established in the Black Horse, a notorious gin shop. These schools would take over existing buildings because they were very basic establishments. The most famous one in the East End is the Dr Barnardo's Ragged School which is now the Ragged School Museum on Copperfield Road just by the canal farther to the east from here. That was old warehouses that were now disused and were taken over by Dr Barnardo himself to establish a ragged school.

"Lord Shaftesbury, who was a peer and a politician, but also a great social reformer, was very interested in child welfare. He was behind a lot of legislation to get children out of working in the mines for instance and factories. He came to visit George Holland's work here, and particularly the ragged schoos to see what the children were like and how they were being cared for and so on. In fact, he was a great admirer of George Holland's work.

"He has left descriptions of the children when he would go and talk to them and ask them how they were and what’s being done for them, et cetera, and they were all full of praise for what George Holland was doing for them, the way he was giving them I suppose some form of structure and security to an otherwise very haphazard existence.

"How long a child was in a ragged school was difficult to answer because of the nature of employment here and because of poverty as well. Families were keen to have their children at work at the earliest possible opportunity. We know [about] Charles Dickens, for instance, (I know this was not his area), but when his father was imprisoned in the Marshalsea Prison, Dickens was taken out of school at the age of 12 and sent to work. This was 1824 when 12 years old was plenty old enough to be put to work.

"The children would be put to work at much earlier ages than that and often in family businesses. They would be sent to a ragged school presumably to get them out of their parents' hair for a while but very soon, they would be put to work.

"It would relieve the parents of the burden of looking after them, that’s the thing I suppose. There was a ragged school union but not all ragged schools belonged to that. Some of them were created by individual philanthropists like George Holland here and, as I mentioned, Thomas Barnardo. His ragged school was not part of the union. It was his own creation.

"We don’t have any records for [how many children attended the school]. Unfortunately, we don’t really have a great deal of information about George Holland himself or his work, which is in many ways a great injustice because we know that he inspired quite a lot of people with his work here. He was here from 1850 until he died in 1900 and a number of people were very much inspired by what he did.

"I mentioned Lord Shaftesbury but there was a professional cricketer called C.T. Studd. He and his wife decided to go to China as missionaries and they sold everything before they left and split the proceeds amongst a number of charities and they gave George Holland here a substantial amount of money. There were people who were interested in what he was doing and wanted to support him back here.

"Whether there was any link to church and Christianity, I'm not sure. I imagine that it would be one of these places that would have texts on the wall, biblical texts or exaltations to worship but as far as I know, there were no services held [at 87 Whitechapel Road]. Again as I say, the information is very sketchy so it’s very hard to say."

David Charnick (www.charnowalks.co.uk) was speaking to Shahed Saleem on 23.02.18. The text has been edited for print.

Ragged School, George Yard, St. Jude's, Whitechapel

Contributed by amymilnesmith