Whitechapel Gallery, former Whitechapel Library

2009 extension to Whitechapel Gallery housed in former 1891-2 Passmore Edwards Library. Incorporates entrance to Aldgate East tube station

Early history of the site of the former Passmore Edwards Library

Contributed by Survey of London on July 10, 2018

Whitechapel Gallery has since 2009 consisted of two buildings – the original gallery, opened in 1901 and to its east the former Passmore Edwards Library, built ten years earlier. The library, then known as the Free Library, opened in 1892, another initiative of Samuel Barnett, the vicar of St Jude's church and founder of Toynbee Hall, both in Commercial Street.

The library building occupies the site of several buildings which by 1818 were in single ownership.1 These included the former 77 to 80 High Street, four small timber-framed houses (all refronted in brick by 1884), there by 1638 when Eleanor Ireland, widow of Westminster, took a lease of them from the Dean and Chapter of St Paul, which had held land in Stepney since the thirteenth century, much depleted by the sventeenth.2 The houses were described as with 12ft frontages and ‘little garden plots’, and were then in the occupations of a weaver, a translator (a cobbler), a collarmaker and a scrivener. Subsequent use was typical of the High Street. At 77 were a gingerbread maker (1841-2), and a ‘commercial coffee house’ from c. 1855 till it was demolished. No. 78, in 1825 when it was a gentleman’s outfitters, sported an ‘excellent bow-fronted shop’; later occupants included a haberdasher, who went bankrupt in 1841, followed by a staymaker and from around 1855 till it was demolished, Godwin Rattler Simpson, patent window- blind maker. No. 79 was a draper’s, latterly Robert Rycroft who moved to No 75 on the demolition of No 79 in 1890.3 No 80 was a jeweller’s, J. Horton & Son, Frederick Horton (d. 1877) in charge for the twenty years before its demolition.4

The library site also included to the rear a substantial brick storehouse, part of the former Swan brewery, discussed in connection with 17 to 25 Osborn Street, and the west side of what had been an alley leading to the brewery. By the mid nineteenth century the alley had become Queen’s Place, which swiftly degenerated into a foul court. The entry to this, about 3ft wide, was through a timber-framed building (No. 81) formerly the Swan with Two Necks (later the White Swan), perhaps rebuilt by the brewer Richard Loton in the 1650s, and from which trade tokens marked with a swan and R.L. were issued in 1650.5 In 1860 Queen’s Place attracted the unfavourable attention of the Whitechapel Board of Works, and thence the Metropolitan Board of Works, for two recently erected three-storey tenements, each about 15ft by 20ft deep, lit only by a narrow gap between them and the infants school in Angel Alley, and the 6ft wide court itself. They were put up on the site of a warehouse on the court’s west side, as, according to the Whitechapel Board’s indefatigable medical officer, John Liddle, the recent slew of warehouses in the new Commercial Street on the site of poor housing had shifted the need from warehouses to housing in other parts of Whitechapel.6 By 1881 there were 48 people living in the four small houses.7

-

Morning Chronicle, 20 May 1818, p. 4 ↩

-

'Stepney: Manors and Estates', in A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 11, Stepney, Bethnal Green, ed. T. F. T. Baker (London, 1998), pp. 19-52: London Metropolitan Archives, Survey of London notes on Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s records ↩

-

Post Office Directories (POD): Census: Morning Advertiser, 11 Aug 1825, p. 4: Morning Advertiser, 14 Feb 1856, p. 8: Journal of the Society of Arts, 15 Jan 1858, p. 136 ↩

-

POD: The Watchmaker, Jeweller and Silversmith’s Trade Journal, 5 May 1877, p. 276 ↩

-

British Museum, T.3963 ↩

-

Builder, 28 Dec 1861, p. 892: Metropolitan Board of Works Minutes, 6 Jan 1860, p. 4; 10 Feb 1860, pp. 116-17 ↩

-

Census ↩

Former Whitechapel Free Library, later Passmore Edwards Library

Contributed by Survey of London on July 10, 2018

Between 1892 and 2005, what is now the eastern half of Whitechapel Gallery was the Whitechapel Library. The library originated, like the gallery, with Henrietta and Samuel Barnett and their colleagues at Toynbee Hall. The Barnetts had established a small lending library within the parish school at St Jude’s almost as soon as they arrived in Whitechapel in 1873. This expanded, becoming a lending library to the George Yard Mission, and to other educational establishments around London, and was eventually housed in Toynbee Hall, first in the dining room and from 1889 in a purpose-built addition. Barnett saw the need for a borough library but, despite the efforts of a committee on which he served, chaired by Whitechapel’s rector, J.F. Kitto, the first vote among the parishioners in 1878 rejected the idea of adopting the Public Libraries Act (which allowed local authorities to levy a rate to pay for free libraries). Reservations were expressed among those generally in support that the Act’s limit of 1d in the pound would not yield sufficient to pay for the library, despite offers in kind and cash of £1,000, and from those in opposition that ‘an already overtaxed community’ should not be called on ‘to fund a Public Library wherein idle people may enjoy themselves’ . 1

Barnett expressed his regret on that occasion that so many ratepayers should ‘pit their stomachs against their brains’. 2 By 1889 Barnett was able to harness the resources of Toynbee Hall, with 100 volunteers campaigning door to door in Whitechapel in support of adoption of the Act (‘the effects of systematic and vigorous canvass were never better illustrated in the entire history of the movement than in Whitechapel’), which was passed on a high turnout of ratepayers by a majority of four to one.3 Fundraising had yielded nearly £5,000 when Barnett had the perspicacity to show the Cornish philanthropist John Passmore Edwards around in 1891, a visit that secured from him a cheque for £6,454, the full cost of the building, the first of many public library buildings in London for which he was to pay.4

The newsrooms were openened to the public on 9 May 1892, with a formal opening of the building by Lord Rosebery, Chairman of the LCC and Foreign Secretary, on 25 October 1892. The builder was Walter Gladding of Baker’s Row, the architects Potts, Son, and Hennings (Edward Potts and William Edward Potts, father and son, of Oldham, and Arthur William Hennings, recently fledged pupil of Sir John Sulman), who had attracted the Commissioners’ attention, perhaps, with their design for Wimbledon Library. The style is similarly non-partisan, a salmagundi of Renaissance and Tudorbethan snippets, with asymmetrical shaped gables, an oriel window, moulded terracotta friezes, ‘gambolling cherubs’ by R. Caldwell Spruce of Burmantofts in the spandrels of the entrance, and a square central tourelle.5

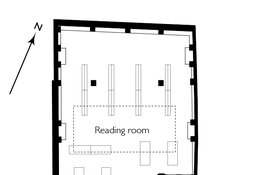

The building occupied a relatively narrow site, only 48ft wide and 130ft deep. A central door led to a small lobby leading to a passage flanked to the left by the closed-access lending library, with narrow borrowers’ area by the door, and to the right small separate boys’ and girls’ reading rooms. Beyond the children’s rooms the passage opened out into a staircase hall. The full width of the ground floor beyond was taken up with the main newsroom and reading room, top lit, though only partially, as on the first floor above, with arch- braced queen-post roof, was a room devoted to the natural history collections of the Rev. Dan Greatorex, vicar of St Paul, Dock Street. 6 Across the front of the first floor was the reference library, and above it librarian’s offices and a caretaker’s flat. To counteract the dimness of the reading room, electric lights were installed, unusually early and before the board had built its generating plant in Osborn Street, which meant the library had its own generator.

Passmore Edwards’ vanity was almost equal to his generosity, and Barnett arranged for the library to be renamed the Passmore Edwards Library in 1897, to forestall Edwards’ wish to have the Whitechapel Gallery, for whose building he also paid, being named after him.

With its association with Toynbee Hall, the library established its outreach mission from the start, the library and museum open seven days a week till 10pm, with monthly lectures, and loans available to schools from the museum collection. By the end of 1903 the museum, its collection augmented by ‘Egyptian antiquities, of dried plants and of fossils (from the Geologists’ Association in 1896), and many native weapons from the Fiji Islands and elsewhere’, was attracting 70,000 visitors a year. 7 Since 1895 its curator had been Kate Marion Hall (1861-1919), a protégée of Henrietta Barnett at Toynbee Hall where she had been teaching nature studies since 1891. Her appointment made her the first professional woman curator in the country.8

After 1900, and absorption of Whitechapel into the new London Borough of Stepney, the policy of Stepney was to centralise the reference work by concentrating the more important and costly books at the Borough Reference Library in Bancroft Road. But Whitechapel Library retained an unrivalled reference collection, strong in Judaica, and its first-floor reference library established a role as the ‘university of the ghetto’. [^9] In 1905 the district Librarian, William Weare, in response to a patronising reference to East End libraries, could claim that the library had ‘helped many private students to obtain University, Commercial and other scholarship, and the Japanese Minister of Education, German, American and other Foreign Professors have expressed their surprise and pleasure when, on visiting the library, they have seen the Reference Library full of earnest students’. 10

In 1922 minor alterations were made when the library converted to open-access. 11 In 1930 a children’s library was established in the basement, and alterations were made to the reference and lending rooms by Stepney Borough Council’s works department. 12 More substantial was the insertion in 1938 of a new entrance at the east end of Aldgate East underground, replacing the lefthand window in the frontage with a curved perron stair clad in cream tiles, typical of the New Works Programme of the newly established London Transport. 13

Bombing in 1940 damaged the roof, and repairs truncated the righthand gable. By 1948, though the late-night opening had ceased, the Greatorex collection still formed the nucleus of the museum, augmented by local antiquities, ‘miscellaneous objects’ and ‘a permanent exhibition of live tropical fish’ 14

In 1963 the lobby was enriched by the addition of a fanciful painted tile panel of ‘Whitechapel Hay Market, 1788’, by Charles Evans & Co., west London art-tile and glass makers, made in 1889 for the Horns public house, at 16 Whitechapel High Street, demolished c. 1961. 15

In 1987 an English Heritage Blue Plaque to the poet Isaac Rosenberg, one of the many ‘Whitechapel Boys’, painters and poets who included Mark Gertler, David Bomberg and the sculptor Osip Zadkine, and often met in the library, was added to the frontage.16

-

East London Observer (ELO), 11 May 1878, p. 6; 25 May 1878, p. 6; 7 Dec 1878, p. 7: Pall Mall Gazette, 11 Dec 1878, p. 6 ↩

-

ELO, 14 Dec 1878, p. 6 ↩

-

Globe, 28 July 1891, p. 6: Thomas Greenwood, Public Libraries : A History of the Movement and a Manual for the Organization and Management of Rate-supported Libraries, London 1891, pp. 338-9 ↩

-

London Evening Standard, 5 Dec 1889, p. 3: Henrietta Barnett, Canon Barnett: His Life, Work and Friends, 2 vols London 1918, vol. 2, pp. 4-8: E. Harcourt Burrage, John Passmore Edwards, Philanthropist, London 1902, pp. 51-3: St James’s Gazette, 27 Feb 1892, p. 7 ↩

-

Nikolaus Pevsner, Bridget Cherry and Charles O'Brien, Pevsner Architecural Guides, London 5: East, London 2005, pp. 72, 78, 399-400 ↩

-

London Daily News, 26 Oct 1892, p. 3: ELO, 29 Oct 1892, p. 7 ↩

-

A Pictorial and Descriptive Guide to London, London 1901, p. 310: The Museums Directory, London 1904, p. 142: Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, xv, London, 1899, p. 58 ↩

-

Leanne Newman, 'Kate Hall "A Fellow of the Linnean Society and creator of a beautiful and famous municipal garden"', The London Gardener, 21, 2017, pp.11-25 ↩

-

Reginald Arthur Rye, The Libraries of London: A Guide for Students, London 1908, p. 22: Elaine R. Smith, 'Class, ethnicity and politics in the Jewish East End, 1918-1939, Jewish Historical Studies, 32 (1990-1992), pp. 355-369: Sarah MacDougal, '"Something is happening there": early British modernism, the Great War and the Whitechapel Boys', in London, Modernism and 1914, ed. Michael J.K. Walsh, Cambridge 2010, pp. 122-47 ↩

-

The Library World, vii/83 May 1905, p. 312: B’nai B’rith News, ix/8, April 1917, p. 7 ↩

-

Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives (THLHLA), L/SMB/E/1/15: LMA, District Surveyor's Returns (DSR) ↩

-

THLHLA, L/SMB/E/1/17: DSR ↩

-

THLHLA, L/SMB/G/1/38/1 and 2: John P. McCrickard, ‘LPTB New Works Programme 80th Anniversary: A Tribute to a Major Expansion of the Underground Network', accessed at lurs.org.uk ↩

-

S.F. Markham, Directory of Museums and Art Galleries in the British Isles, London, 1948, p. 232 ↩

-

http://www.tilesoc.org.uk/tile-gazetteer/tower-hamlets.html ↩

-

THLHLA, L/THL/H/1/4/15: English Heritage Blue Plaques file notes, courtesy of Howard Spencer: MacDougall, op. cit.: information on Zadkine's presence in Whitechapel kindly supplied by Cathy Corbett ↩

Kate Marion Hall and The Whitechapel Museum

Contributed by Leanne Newman on Oct. 9, 2017

In 1895, Kate Marion Hall, (1861-1919), was appointed Curator of the Whitechapel Museum making her the first woman in the country to hold such a professional position. Kate was a protégée of the social reformer and philanthropist, Henrietta Barnett, whose work in the East End attracted a number of young middle-class women to the area as volunteers. Kate had started work in the East End in 1891 when she began teaching nature studies at the Natural History Society at Toynbee Hall.

One of the ways Henrietta and her husband, Canon Barnett, sought to improve the impoverished lives of working people in 1890s Whitechapel was through education. To achieve this they established The Whitechapel Library which gave free access to books, the Whitechapel Art Gallery with its free access to art exhibitions and Toynbee Hall which provided a wide range of educational courses also free of charge.

When the Whitechapel Library was opened in 1891, a room was set aside on the second floor to serve as the Whitechapel Museum with Kate's mentor, the botanist and geologist, Alfred Vaughan Jennings as its first curator. The museum housed the "menagerie of natural history specimens" collected by the Reverend Dan Greatorex (1829-1901), also known as the Sailor's Chaplain. Greatorex was a social reformer renowned for his work with the poor in the East End, which included "a maternity benefit fund, numerous schools and nurseries and a Children's Temperance Society."1

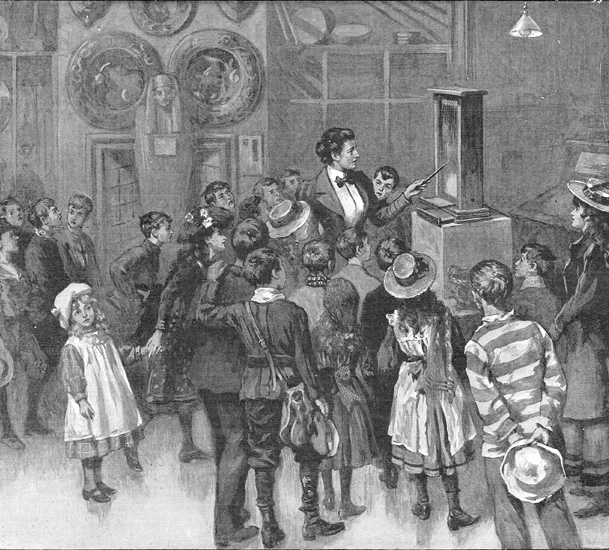

'Practical lessons in elementary science in Whitechapel: An exhibition of living bees', from The Graphic, 10 Nov 1900

Although part of his collection came from gifts given to him by British and foreign sailors grateful for his help, many other artefacts were collected by Greatorex on his own travels around the world, which included voyages to the Middle East, Canada, the South Pacific and South America. These included exotic specimens of sea creatures as well as spears, axes and clubs belonging to"cannibals and headhunters."2

When Kate succeeded Jennings as curator, she regarded the most important aspect of her work at the museum to be the organisation of nature study lectures and demonstrations for school children living in one of the most polluted and deprived areas of the country. Kate was innovative in her teaching methods, providing local school teachers with a carefully planned syllabus with which to introduce the children to the basics of nature studies prior to their visit to the museum. She also arranged displays of flora and fauna which were changed weekly and which the children were invited to handle. In this way, nature study, which had only recently been added to the curriculum of elementary school education, was seen as the study of living things.

Museum opening hours were extended to 10 pm, so that working men and women could visit the museum their children had told them so much about. The museum attracted huge numbers of visitors. Henrietta Barnett later recalled:

"Many people came to that little museum, no less than 104,406 in two years, the majority of whom were shown by Miss Hall wonders such as the observatory beehive, the wasps nest etc.."3

The museum's success attracted gifts of Egyptian artefacts from F.D. Mocatta and rare specimens given to the Duke and Duchess of York ( later King George V and Queen Mary) on their royal tour of New Zealand in 1901. In 1903, the museum became the Stepney Borough Museum, the first municipal museum to be funded by local rates. Kate was well known throughout the wider male-dominated museum fraternity who held her in high esteem. She retired from the museum in 1909.

For further information about Kate Hall's life and work see :

Leanne Newman, 'Kate Hall "A Fellow of the Linnean Society and creator of a beautiful and famous municipal garden"', The London Gardener, London Parks and Garden Trust, Volume 21, 2017, pp.11-25.

Whitechapel reference library, 1971

Contributed by Survey of London on Dec. 19, 2016

A view of the reference library in 1975, from a digitised colour slide in the collection of the Tower Hamlets Archives:

Old Whitechapel Library frontage, August 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Former Passmore Edwards Library, Whitechapel High Street, in 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Whitechapel Library, ground-floor plan as built in 1892, drawing by Helen Jones based on archive sources

Contributed by Survey of London

Weather Vane of Erasmus reading 'In Praise of Folly' while riding a horse backwards

Contributed by david2

Barnard Kops read 'Whitechapel Library, Aldgate East'

The poet and playwright Bernard Kops (b. 1926) reads his poem 'Whitechapel Library, Aldgate East', in May 2015

Contributed by Survey of London on March 12, 2018