Giles Kinchin and the Mulberry Garden

Contributed by marion on June 10, 2017

My ancestor, Giles Kinchin, gardener of Ratcliff, acquired the lease to the

Mulberry Garden, Mile End Old Town, in about 1679. No deed survives, but from

the baptisms and burials of his children at St Dunstan, Stepney, and St Mary,

Whitechapel it is apparent that Giles and his wife moved to Mile End Old Town

at around that date.

Two generations of the Kinchin family lived and worked at the Mulberry Garden

until 1729, and were members of the Clothworkers' Company, in whose records

can be found details of at least ten apprentices that were bound to them in

that period.

The tax return of 1693/4 or ‘ Four Shillings in the Pound Aid’, records Giles

'Kinchen’s' property as having a rental value of £34 to be taxed at £6.8s.

This is in contrast to the extensive nursery ground just north of the

Whitechapel Road of William Gurle, son of Leonard Gurle, valued at £25 and

taxed at £5.

The lease of the Mulberry Garden passed to John Martyr (who had been

apprenticed to Giles) when he married Ann, his master's widow, in 1705. An

increasing number of Kinchin family members and their apprentices were

dependent on the four-acre Mulberry Garden for their living. By 1732, they

numbered five adults, three children, and three apprentices. As silk

production appears not to have succeeded in England at this time, owing to

silkworms not thriving in the cold climate, it is likely that the Garden was

used as a market garden, and that in the early period, the Kinchin family

benefited from the demand for food from London's expanding population.

John Martyr worked the Mulberry Garden for 18 years until his death in 1723,

leaving the lease to his stepson William Kinchin. On 13 May 1725, William

insured the house for £150, and goods and merchandise at the garden for a

further £150, with the Sun Insurance Company.

By 1728, however, the Garden had failed, and William sold the lease to his

brother-in-law, Rowland Stagg. With only poor relief as a means of

support, William went to New England probably as an indentured labourer.

Rowland Stagg gave testimony in 1734 for the gardener's apprentice, Richard

Hastings, that his master, William Kinchin 'about three years and a half since

being in low circumstances went to Boston in New England and hath lived there

ever since'. William died in Boston in 1746. Rowland Stagg, who ran a

successful cooperage at Great Stone Stairs, Ratcliff, sold the lease of the

Mulberry Garden a few years later.

It may have been a fall in the price of fruit and vegetables that secured the

fate of the Mulberry Garden. Increased pollution from coal fires may also have

meant that the exhausted soil was no longer productive. The land was

eventually sold for development, and the Kinchin family entered the East

London maritime trades.

The Mulberry Gardens

Contributed by Survey of London on Aug. 26, 2016

An approximately four-acre quadrilateral of ground lying west of present-day

Plumbers Row and extending south from the Pierrepoint/Baynes Estate to what is

now Commercial Road was a mulberry garden, densely planted as if an orchard

and laid out with paths in a grid. It might once have extended further east;

its origins remain obscure. Mulberries had been introduced to London by the

Romans and were commonly used for making medieval ‘murrey’ (sweet pottage) as

well as for medicinal purposes, but such a neatly planned grove may have

arisen from James I’s attempt to establish native silk production in 1607–9

when around ten thousand saplings were imported and distributed by William

Stallenge and François Verton through local officials at six shillings for a

hundred plants, less for packets of seeds. Mulberry gardens thus came about

across England, mirrors of the King’s own of four acres in the grounds of St

James’s (now Buckingham) Palace. The commercial project failed, black

mulberries (Morus nigra) having been acquired rather than the white (Morus

alba) that silkworms tend to favour, perhaps the result of deceit; the supply

chain cannot have been so ignorant. There was a second mulberry garden close

by, across Whitechapel Road in Mile End New Town, north of what is now Old

Montague Street and east of Greatorex (formerly Great Garden) Street, and land

to the east of that south of Old Montague Street appears to have been

similarly planted. Spitalfields was already at the beginning of the

seventeenth century a centre of silk throwing and weaving.

Whitechapel’s so-designated mulberry garden, like that at the palace,

eventually fell to use as a pleasure ground after a period as a market garden

held on a lease from about 1679 by Giles Kinchin and his indirect descendants

up to around 1750 (see separate contribution). After the garden's failure as a

commercial venture in the 1720s it appears that Rowland Stagg adapted the

premises to be a pleasure ground. There was a garden house near the north end

and recreational use continued up to at least 1760, the arrest then of four

young gamblers by Sir John Fielding’s runners indicating anxieties about the

presence of vice. An executed pirate refused burial elsewhere was interred in

the otherwise disused grounds in 1762.

The Mulberry Garden ‘behind Whitechapel Church’ was made new use of for a few

weeks in late 1764 as a temporary asylum, a tented camp for around 400

deceived and destitute refugees from the Palatinate and Bohemia who had been

abandoned on what they had undertaken as a journey to Nova Scotia. Helped by

exhortations to charity and by local people, notably other Germans, in

particular Dr Gustav Anton Wachsel, the refugees were able after all to depart

and, following a petition to King George III, to settle in South Carolina. The

garden remained untenanted until 1772 when John Holloway, a Goodman’s Fields

cooper, acquired the property and adjoining lands (about 4.5 acres in all)

with a handful of houses from Stepney manor for building.

Developments from 1784

Contributed by Survey of London on Aug. 26, 2016

Under Holloway’s ownership streets were laid out from 1784 with more than 150

small two- and three-storey houses, up by the 1790s on leases of from 61 to 81

years. Union (Adler) Street was formed where Windmill Alley had branched from

Whitechapel Road. What had been Johnson’s rope walk to the east, then Baynes

Passage, became Plumber’s Row, probably because a property at the north end of

its west side pertained to Alderman Sir William Plomer. Great Holloway Street

and Little Holloway Street ran east–west on the present line of Coke Street,

and Mulberry Street crossed as what is now Weyhill Road continuing north to a

small open space that John Prier laid out as Sion Square in 1788–9. Greater

density was interposed with the formation from 1788 of Chapel Court between

Union Street and Mulberry Street; that finished up in the twentieth century as

Synagogue Place.

Sion and Chapel have their explanation in the adaptation of an attempt to

sustain the allures of the place as a pleasure ground. A large site on the

east side of Union Street, 100ft by 160ft, was taken in June 1785 with an

81-year lease by George Jones, a ‘riding master’, with James Jones in

partnership. They built a ‘riding school’ that incorporated ‘scenery and

machinery’. This early circus opened in April 1786 as ‘Jones’s Equestrian

Amphitheatre’. It had a copper-covered dome, its ceiling perhaps decorated

with ‘painted palm-trees and other forms’, atop a circle of about 100ft

diameter with galleries on a ring of columns for a capacity of 3,000 to

witness the display of ‘a great variety of incomparable horsemanship, and

various other feats of manly activity’.With William Parker, George Jones

also held the other side of Union Row (present-day Mulberry Street) including

the Union Flag public house. The circus venture folded in April 1788 with a

send-off that included non-equestrian acts from Sadler’s Wells and Philip

Astley’s Royal Grove. Astley’s Riding School and Charles Hughes’s rival Royal

Circus, Equestrian and Philharmonic Academy, both close to Westminster Bridge

on the Surrey side, had probably inspired if not actually produced the Joneses

in the first place.

At its closure the amphitheatre had been let for conversion to use as a chapel

for the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion. Founded in 1783 as a dissenting

denomination, the Connexion had already converted another circular pleasure

pavilion, the Spa Fields Pantheon in Clerkenwell. The Union Street building

became the Sion (or Zion) Methodist Chapel, a stronghold of Calvinistic

Methodism that had its own school.

Elsewhere on what had been Mulberry Gardens the Mulberry Tree public house

stood on the north side of Little Holloway Street. The south end of Holloway’s

estate, where the road frontage to White Horse Lane became the west end of

Commercial Road, was by 1794 the site of Severn, King and Co., substantial

sugar-bakers. Their property was extensively developed with a new 71-year

lease granted to Benjamin Severn and Frederick Benjamin King in 1816. The

sugar house burnt down in 1819 and the insurers refused to pay the loss, a

cause célèbre. Rebuilding of a fireproof character ensued along the lines of a

Mr Howard’s patent. But bankruptcy followed in 1829; the property was taken on

by Fairrie Brothers and Co. by the time Holloway’s estate as a whole was sold

off at auction in 1839. The refinery passed to Candler & Sons in the

1860s and was used for sugar and other warehousing up to the 1920s. There was

then rebuilding for garages that included a petrol station to the west.

This locality was for most of the twentieth century an important centre of

Jewish institutions, notably two venerable synagogues displaced from the City

that were constituents of the United Synagogue. The east side of Union Street

south of Holloway Street was redeveloped in 1897-9 for the New Hambro

Synagogue. This Jewish congregation, one of London’s oldest, moved from the

City of London under Chief Rabbi Dr Hermann Adler (1839–1911), the son of and

successor to Chief Rabbi Nathan Marcus Adler, founder of the United Synagogue.

Lewis Solomon was the architect of a substantial and outwardly four-square

Italianate building, with two entrances for men and one for women facing Union

Street. The uppermost storey housed a committee room and caretaker’s flat. The

interior seated 370 and had an unusual arrangement, with flights of stairs

rising either side of the Bimah to reach the gallery at the Ark or east end

for overflow male seating. The ladies gallery was to the west.

The street was renamed Adler Street in 1913 and the property extended round to

Mulberry Street for a Jewish Court to the south. The district had become

predominantly Jewish, with some Germans still present. Booth’s survey noted

tailors and bootmakers as prevalent in 1898, registering general good repair

and ‘the constant whirr of the sewing machine or tap of the hammer as you pass

through the streets’, as well as ‘the feeling as of being in a foreign

town’. By the 1930s many of Mulberry Street’s houses were being condemned

as dangerous structures and the synagogue closed in 1936. The London Mosque

Fund attempted unsuccessfully to buy it in 1938–9 before securing property on

Commercial Road.

On the north side of the Adler Street/Holloway Street corner, the Grand Order

of Israel Friendly Society built the Adler Assembly Hall in 1924–5, with F. J.

Cornford as architect. This, which came to be called Adler House, was a neat

three-storey polychrome-brick building with a Star of David between the upper

storeys on a setback at the site’s corner. Its upper floor had a meeting room

and a billiard room. Around 1931 it became the Regina Ballrooms and a boxing

licence was approved in 1934.

Heavy bomb damage in the Second World War led to the clearance of almost

everything east of Mulberry Street, all but three houses on Plumber’s Row, and

five houses and the Mulberry Tree pub on Mulberry Street. Plumber’s Row was

entirely cleared and widened in 1962. The synagogue survived into the 1950s

for use by the displaced Court and as a Jewish Reading Room, which transferred

into Adler House. That had seen temporary war-time use as a synagogue and The

Folkhouse (Beth-Am), then briefly in 1946–7 as the New Yiddish Theatre, before

supporting a further range of Jewish community uses. Finally, from 1958 to

1977, synagogue use returned for the much-diminished Great Synagogue (Duke’s

Place), bombed and then sold out of its historic Aldgate home. After a short

period of commercial use Adler House was demolished around 1990.

The German Roman Catholic Church of St Boniface, Adler Street

Contributed by Survey of London on Aug. 26, 2016

London’s German Catholic Mission acquired Lady Huntingdon’s Sion Chapel in

1861. This congregation had its origins at the Virginia Street Chapel, just

south of Whitechapel in Wapping, in 1808 when there were thousands of German

Catholics in the area, largely employed in sugar refining. A year later the

mission moved to premises in the City that were dedicated to SS Peter and

Boniface, the last (born Wynfrid) appropriate as having been an English

missionary in Germany.

In 1862 there was a thorough refit of the former circus building in a

Romanesque style, overseen by Frederick Sang, a German-born architect and

decorator based in London. It included an 18ft-wide Caen stone altar. A

section of the building east of the amphitheatre was maintained or adapted for

the mission’s school. At the opening the Rev. Dr Henry Edward Manning preached

and Cardinal Wiseman blessed the new church. But in May 1873 it suffered a

spectacular collapse of its domical ceiling and had to be cleared. Manning

helped Father Victor Fick to raise funds for a replacement building. A German

Gothic scheme by E. W. Pugin (who had prepared plans for a building for the

Mission in 1859–60) was superseded by a design from John Young for a loosely

Romanesque building, a style preferred by Manning who attended the opening in

1875. A basilican brick structure, its square west tower incorporated a mosaic

of 1887 showing St Boniface preaching. Set well back from the street, the

church gradually came to be enclosed by later structures. Young oversaw the

addition of a presbytery to the south-east in 1877, a school in 1879, and,

through Father Henry Volk with justification on grounds of a growing immigrant

congregation, eastwards extension of the church with an apse and enhanced

interior decoration in 1882. Stained-glass windows and wooden Stations of the

Cross were of German origin. There were further works in 1885, when bells

made in Whitechapel were added to the tower. In 1897 Father Joseph Verres

gained approval for the formation of a covered playground below a schoolroom

and sanitary block to the north-east. More improvements and an extension of

this block followed in 1907–8 and 1912–13.

Dispersal and expulsion of members of the congregation aside, the German

church suffered heavily the consequences of wars with Germany. It was slightly

damaged in a Zeppelin raid in 1917. Having been confiscated as enemy property,

ownership passed in 1919 to the Catholic Archdiocese of Westminster.

Consecration followed in 1925 when Father Joseph Simml was installed as

priest. Then the church was entirely destroyed in September 1940 by a high-

explosive bomb. Simml, an opponent of Fascism, stayed through the war,

sometimes preaching in the open air. The congregation retreated to the

easterly school buildings which with the presbytery were all that

survived.

Rebuilding was pursued despite the loss of much of the congregation to more

salubrious parts of London. Some remained willing to travel to Whitechapel,

and from 1949 there were also new immigrants, predominantly women, many from

East Germany drawn to work in factories, hospitals and homes, for education or

through marriage, sometimes to British soldiers of the post-war occupation.

Some prisoners of war also stayed on. War-damage assessment was handled for

the Archdiocese by Plaskett Marshall & Son, architects, who prepared a

first conservatively historicist scheme for a new church in 1947. Without

funding this was premature, but on archdiocesan advice the firm was kept on.

Upon the death of the senior partner, his son, Donald Plaskett Marshall, took

control through Plaskett Marshall & Partners.

From 1952 the rebuilding was pursued by Father Felix Leushacke (1913–97),

thinking big in anticipation of future growth and working with Simml, who was

said to have brought a liking for Bavarian Baroque to the project. Alongside

war-damage compensation there was to be financial help from the West German

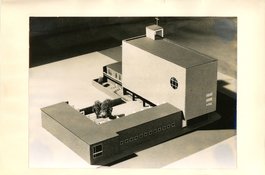

government. The first plans for the new building disappointed Leushacke so in

1954 he involved a German architect and friend, Toni Hermanns of Cleves

(Leushacke’s birthplace). Hermanns visited the site, prepared numerous

possibilities in sketches and then presented worked-up plans and a model that

were photographed and published. The model and preliminary sketches survive at

the church. Hermanns, a powerfully imaginative architect best known for the

Liebfrauenkirche in Duisburg of 1958–60, proposed a cuboid block, to be lit by

numerous small round windows in a radiating pattern on its long west

(liturgical south) elevation. The Archdiocese vetoed the scheme – Leushacke

quoted its response as ‘Never!’, upon which Plaskett Marshall said (an

assertion that he was to remain in control in Leushacke’s view), ‘And now you

leave the dirty work to me!’ Plaskett Marshall worked up revised plans in

close if fraught consultation with Leushacke in 1955–6, encountering many more

objections from Bishop George Craven at Westminster. The scheme was settled

with approval from the newly installed Archbishop William Godfrey in 1957

after debate over the cubic or auditory nature of the main space,

progressively non-processional for a Catholic congregation at this date. Higgs

& Hill Ltd undertook construction beginning in November 1959 and the new

Church of St Boniface opened in November 1960, Cardinal Godfrey being present

at both the start of work and the opening. A building of some architectural

panache, the Church of St Boniface is unlike other work by Plaskett Marshall

and does seem in significant measure to reflect Hermann’s approach and

aesthetic, though Hermanns was not involved after 1954. Wynfrid House,

adjoining and also by Plaskett Marshall, supplies telling comparative

evidence.

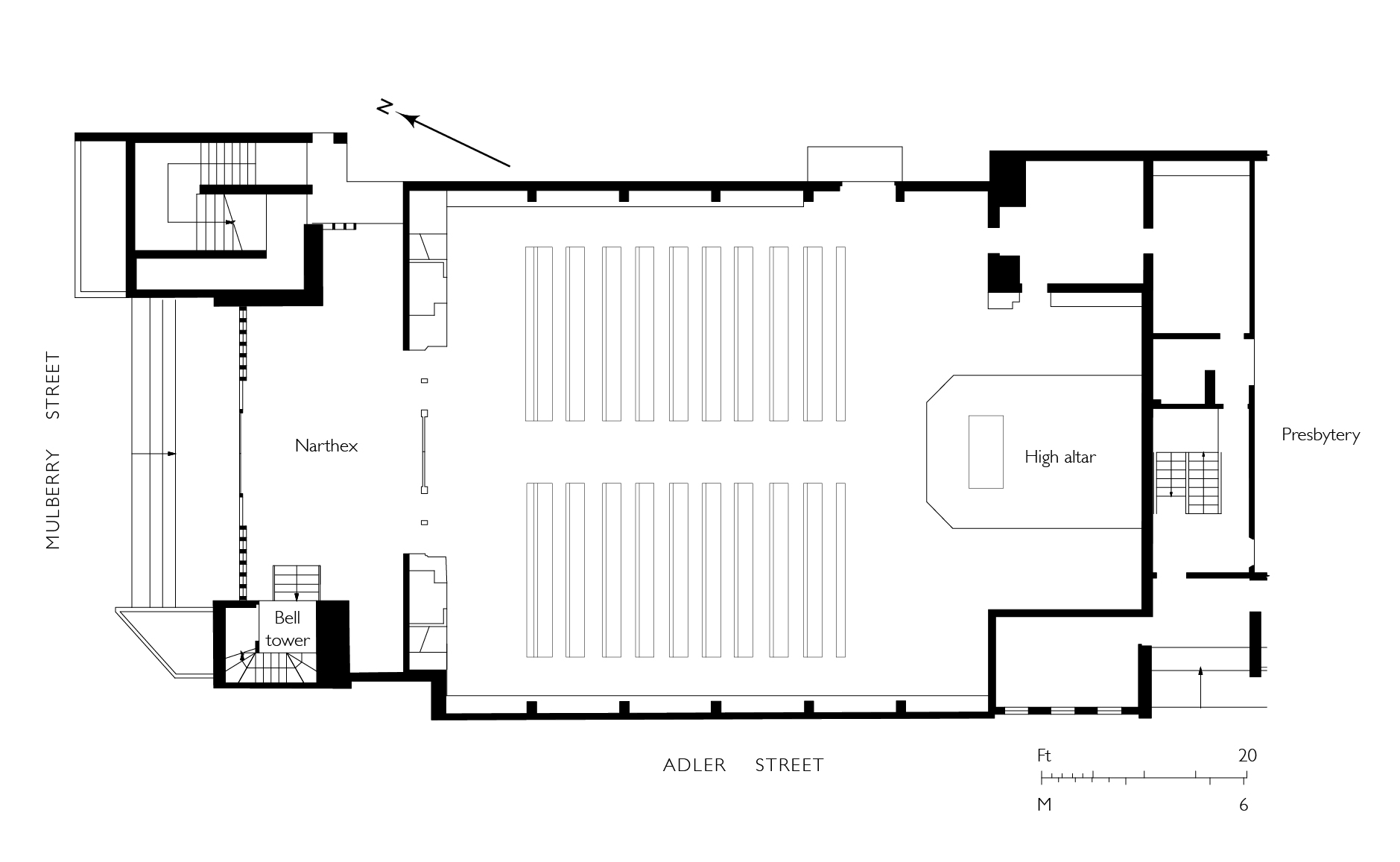

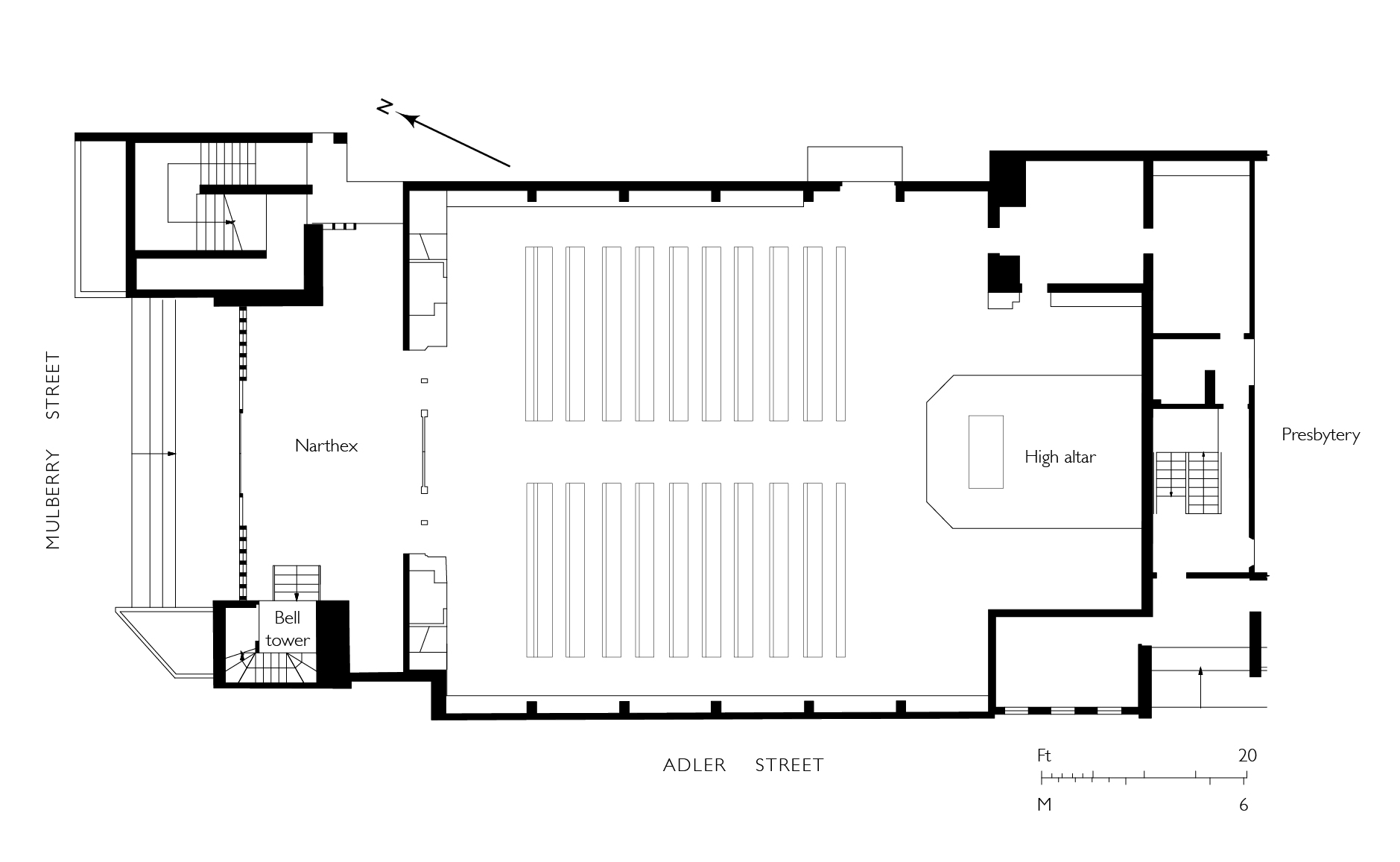

The presbytery to the rear on Adler Street was ready by 1962. There were

seatings for 200 in the nave and 60 in the gallery, within a concrete-cased

steel portal-frame structure. The main walls are of hand-made dark-brown

bricks rising to a clerestorey above which concrete eaves cast (unusually) on

plastic-lined shuttering for a coffered effect underlie a copper roof supplied

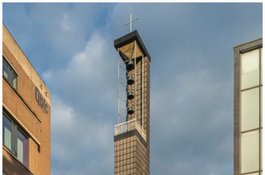

by the Ruberoid Co. Ltd. A Westwerk houses a timber-lined narthex and has

small coloured-glass cross windows in square patterning to its upper-storey

façade. The south-west tower rises 130ft with concrete slabs faced with grey-

scale patterning in ceramic mosaics. At its top an open belfry houses salvaged

Victorian bells. This slender and prominent tower was chosen in preference to

central heating, toilets and a vestry room, prestige trumping comfort. The

building as a whole is remarkable for the richness, originality and elegance

of its decoration. The plain three-storey presbytery to the south facing Adler

Street contrasts with ochre two-inch bricks.

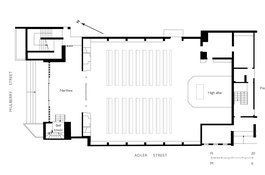

Plan of the

Church of St Boniface as in 2017 (drawing by Helen Jones)

Plan of the

Church of St Boniface as in 2017 (drawing by Helen Jones)

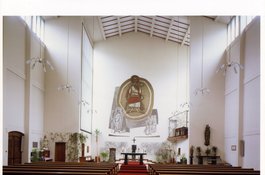

The church interior is spacious and light, generally white in its surfaces

setting off fittings and stained glass of distinction. The high altar, Lady

Altar, tabernacle plinth, and a quasi-triangular font are all of a dark green

marble, with a chancel floor of white Sicilian marble, enlarged after Vatican

II. On the south (liturgical east) wall there is a large sgrafitto mural of

Christ in Glory above St Boniface preaching to the faithful, made by Heribert

Reul of Kevelaer, near Cleves. Figurative and decorative wrought iron is by

Reginald Lloyd of Bideford, Devon – four panels (altar rails resited as a kind

of reredos) and a gallery front depicting the Crucifixion with the Nativity

and the Resurrection. An ambo or pulpit front depicting the parable of the

sower has been removed since 2003. There is a lectern of 1980, made by Lloyd

to mark the 13th centenary of St Boniface’s birth in Devon. The font has a

bronze cover commemorating Simml (d.1976), also by Reul. To the north

(liturgical west) the gallery front has the Stations of the Cross, relief

carvings from Oberammergau (by Georg Lang selig Erben), eleven of fourteen

dating from 1912 and reused from the old church. The organ of 1965 was made by

Romanus Seifert & Sohn. A spectacular stained-glass window by Lloyd above

the gallery depicts Pentecost. The congregation began to disperse and

dwindle and since the 1970s the church has been shared with a Maltese

community.

Memories of World War II from the Family Gilford

Contributed by Sarah Milne, Survey of London on June 8, 2017

Tony Gilford recalls his family's connection to St Boniface focusing on what

it was like during World War II:

I was just 130 days old on 3 September 1939 and probably with my Dad (1912)

and Mum (1910) at the start of the 11 o'clock high mass at the St Boniface

German Catholic Mission Church in Aldgate, London E1. At 11.15am in this very

hour, history records, the primeminister Neville Chamberlain was making his

BBC Home Service radio broadcast speech to the nation declaring war on

Germany. Of course I do not recall this event personally.

Every Sunday the St Boniface Church was a friendly meeting place for the

Anglo-German catholic community in London: butchers, bakers, hairdressers,

jewellers, waiters, wine merchants, domestic staff, musicians, au-pairs, etc.

Some were born in England but with one or both parents of German lineage.

Some, especially the older generation like my grandparents, born in Germany

but had emigrated to England and taken up British naturalisation before 1939.

Some were recent German migrants staying with families to learn English, find

employment, perhaps a new homeland. My parents, Peter and Lily Gilford, had a

corner back street shop and bakery at 72 Marmont Road in Peckham SE15. A ride

across Tower Bridge on a 78 bus and a short walk along Whitechapel Road led to

St Boniface Church in Adler St.

Our paternal grandparents, Peter and Monika Gilsdorf, originally lived in a

small village, Nagelsberg, Wurttemberg, south Germany, before emigrating. My

own Mum and Dad were born in London before WWI, spent their childhood as

refugees repatriated to Germany, and came back to London in the late twenties.

Master bakers and butchers were exempted from military service but many of the

St Boniface young men volunteered or were conscripted.

Plan of the

Church of St Boniface as in 2017 (drawing by Helen Jones)

Plan of the

Church of St Boniface as in 2017 (drawing by Helen Jones)