Petticoat Lane's early history

Contributed by Survey of London on Aug. 3, 2020

Petticoat Lane ‘is not what it used to be’. This lament has echoed through

recent decades, as demography and shopping habits continue their perpetual

churn, but it is older. An aura of nostalgia has clung to Petticoat Lane from

its earliest times. In the 1590s John Stow bemoaned the transformation of

Hog Lane, as it was then generally known: ‘This Hogge lane stretcheth North

toward Saint Marie Spitle without Bishopsgate, and within these fortie yeares,

had on both sides fayre hedgerowes of Elme trees, with Bridges and easie

stiles to passe ouer into the pleasant fieldes, very commodious for Citizens

therein to walke, shoote, and otherwise to recreate and refresh their dulled

spirites in the sweete and wholesome ayre, which is nowe within few yeares

made a continuall building throughout, of Garden houses, and small Cottages;

and the fields on either side be turned into Garden plottes, teynter yardes,

Bowling Allyes, and such like, from Houndes ditch in the West, so farre as

white Chappell, and further towards the East.’

This suggests both that the line of the street was built up between 1550 and

1600 and that the hinterland remained undeveloped. Stow is inexact, but it has

been suggested that the reference to tenteryards refers to those created on

the City side in the 1570s. Bowling is recorded in the 1530s in a nearby

Whitechapel garden, and in the 1590s William Megges had a bowling alley at his

great house to the east of Petticoat Lane.

Hog Lane to Petticoat Lane

The name ‘Petticoat Lane’ was in use by 1586, when two houses in ‘Petticote’

or ‘Pettycote’ Lane were to be searched in connection with the Babington plot

that led to the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots. One of these houses was

that of John Gage (b. 1563), the recusant grandson of Sir John Gage, Queen

Elizabeth’s sometime chamberlain, and younger brother of Robert Gage who was

executed for his part in the plot.

Petticoat Lane appears to owe its name to a different kind of illicit

activity. Hog Lane, even when still so called in the late sixteenth century,

was the location of a well-known ‘disorderly’ house owned by John Holland,

part of a ‘mobb’ with brothels dotted around London. In a pamphlet of

1591, Thomas Nashe (as ‘Adam Fouleweather’) wrote that ‘if the Beadelles of

Bridewell be careful this summer it may be hoped that Peticote Lane may be

less pestered with ill aires then it was woont: and the howses there so cleere

clensed, that honest women may dwell there without any dread’. The

following year, Robert Greene relayed a fictional tale of a confidence trick

or ‘cross bite’ in a ‘Trugging house’ in ‘Petticote Lane’. In 1596 the

libertine-turned-Catholic, Thomas Lodge, poured scorn on an imaginary ‘lord of

all bawdy houses, & Patron of Peticote-lane’.

A similar imputation of general disreputability occurs in 1601 in Thomas

Middleton’s pamphlet The Penniless Parliament of Threadbare Poets which

postulates as an implausible scenario that ‘men shall be so vent'rously given

as they shall go into Petticoat Lane and yet come out again as honestly as

they went first in’. There is a more specific suggestion that Petticoat Lane

was a haunt of sexual vice in a pamphlet by Samuel Rowlands, based on the work

of Robert Greene, about a ‘whore’, who, in a common trope, had tried to

facilitate theft from a client in her lodging ‘which was in Peticote

Lane’. The use of the word ‘petticoat’ for a prostitute and the

substitution of ‘Petticoat Lane’ for ‘brothel houses’ in different editions of

Middleton’s work have also been noted. The suggestion has further been made

that the ‘Garden houses’ referred to by Stow were, in fact, these

brothels. In 1632 Donald Lupton opined that Petticoat Lane and Rosemary

Lane (another former Hog Lane that gained notoriety as a clothes market)

housed populations of women who ‘traded on their bottom’.

Such commentary does not constitute a dispassionate archival source, but while

the accounts are undoubtedly embroidered for sensational effect, these

allusions to a specific street, by several different authors, did not come

from nowhere. They are sufficiently numerous, and consistent with late

sixteenth-century Bridewell court records, which show Aldgate as one area

where prostitution was concentrated, to allow the inference that the street’s

name derived from the lewd associations of ‘petticoat’ rather than,

anachronistically, from the area’s later popularity as a locus of trading in

second-hand clothes. That must be noted because a literal interpretation

of the word ‘petticoat’ has been conflated with the beginnings of the street

market. No such link is necessary.

What is not specified in these sources is what part of Petticoat Lane, which

stretched from the junction with Whitechapel High Street north almost to

Bishopsgate Street, is referred to in the allusions to bawdy houses. In Ben

Jonson’s The Devil is an Ass, first performed in 1616, the character of

Iniquity suggests he will ‘lead thee a daunce, through the streets ... Downe

Petticoate-lane, and vp the Smock-allies’, which suggests an area further

up the lane in Spitalfields, the location of Smock Alley. Other early

references to ‘Peticote Lane’ merely as a street name occur in 1602

(specifying only that it is ‘in London’) and more precisely in 1604, when

property, probably an inn, ‘on the east side of Petticoat Lane’, was held of

Sir Thomas Bodley by John Wright, the innholder at the Crown in Aldgate High

Street at his death in 1607. Little can be said about the lane’s early

residents. In the 1750s William Maitland noted that the Whitechapel end of

Petticoat Lane was ‘not mighty well [affluently] inhabited. Those of the most

account are Horners, who prepare Horns for other petty Manufacturers.’

This had been the case for nearly a century. Banished from the City, the

noxious trade had concentrated around Petticoat Lane. The most substantial

horner was George Harrison, resident in Petticoat Lane by 1666 until his death

in 1706. He held several leases on the east side of Petticoat Lane around

Tripe Yard and Swan Court, including that of his own house with a high rental

value in 1693 of £50, as well as other leases in Old Montague Street and

elsewhere in East London. Other houses of reasonable size, clustered in

the centre of the Whitechapel stretch of Petticoat Lane, were occupied by

horners in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, including

William Axtell (d. 1690), Edward Edwards (d. 1727), William Layton (d. 1728)

and John Abraham (1700–67). The only other substantial resident of this

period seems to have been Edward Lloyd (_c._1620–96), a ‘merchant … and late

of Mary Land, planter’. Lloyd was an ambitious Puritan emigrant who had

returned to England in 1668 and died in Petticoat Lane in possession of

thousands of acres and many slaves in Maryland. He was resident in Black Bell

Lane in a ‘Great Howse’ with a garden and orchard from 1689 to the end of his

life.

Petticoat Lane to Middlesex Street

The process of ‘pestering’ with tenements and courts that Stow bemoaned took

off in Petticoat Lane around the time that the customs of the Manor changed in

1617, and proceeded apace throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

When William Browne acquired a Boar’s Head Yard holding in 1621, he already

held land in Tripe Yard, a narrow alley that eventually connected with the

north end of Boar’s Head Yard to occupy together more than a third of the

Petticoat Lane hinterland between the High Street and Wentworth Street, with

access to both the High Street and Petticoat Lane.

By the 1670s there were more than 200 houses on the Whitechapel section of

Petticoat Lane and the alleys and courts leading off it. Of those recorded

fewer than twenty per cent had four or more hearths; more had only one.

Typical perhaps of the two- or three-hearth houses was that leased in Boar’s

Head Yard in 1669 to the horner William Axtell, whose larger principal

dwelling fronted the lane. It was of brick, of four storeys including a

cellar, with only one room on each floor. Hollar’s aerial ‘Surveigh’ of

the post-Fire City of 1667 stretches as far as this corner of Whitechapel, and

shows in a schematic but realistically representative manner a continuous line

of two and three-storey mostly gable-fronted houses of modest width along

Petticoat Lane. By 1676, there were thirteen courts or alleys off Petticoat

Lane on the Whitechapel side, including minor but proper streets, Three Tun

Alley, Black Bell Alley (on the line of New Goulston Street) and Horseshoe

Alley.

Apart from horners and the poor, Petticoat Lane’s closed-off back alleys

provided a home for religious nonconformists. There was a meeting house by

1723, perhaps much earlier, on part of the site of the Boar’s Head Theatre. It

passed from Independents to Anabaptists around 1765, on to Calvinists in the

early nineteenth century, and finally became a synagogue, with stables

beneath, until demolition around 1882.

Despite rebuilding and renaming, this dense topography carried on as a locus

of poverty, disease and crime, often, as ever, in brothels. In 1725 Petticoat

Lane was given as an exemplar of a place a ‘boarding school miss’ would be

ashamed to admit was home. A large open area at the end of Black Bell

Alley, marked ‘Blackguard’s Gambling Ground’ on Horwood’s map of the 1790s,

might be identified with a court called the Gaff, where, it was said in 1818,

‘Jews used to play at pitch and toss’.

As Petticoat Lane’s population increased, public houses were established on

its east side. The earliest was the Black Bell on the corner of Black Bell

Alley, present by the mid seventeenth century and later just the Bell, which

pub survives in rebuilt form. Another was the King of Prussia (sometimes the

King of Prussia’s Head), on the Wentworth Street corner by 1767, rebuilt in

1868 but falling to road widening around 1881. The Black Lion adjoined by 1750

and met the same fate. These places were reputed to be haunts of receivers of

stolen goods. The notoriety of the name ‘Petticoat Lane’ saw it replaced,

very gradually, over the nineteenth century by Middlesex Street – it was part

of the county boundary. The new name was first used in 1805 for the part of

the street between Whitechapel High Street and Wentworth Street, but it was

not until the 1830s that it seems to have taken hold, even for legal or

official use. The blandness of the new name coupled with the familiarity

of the old name, meant that even in the 1890s there were references to

‘Middlesex Street (late Petticoat Lane)’ and ‘Middlesex Street, better known

as Petticoat Lane, Whitechapel’. By the end of the nineteenth century the

whole street to Bishopsgate was Middlesex Street. In a final turn of the

Petticoat Lane wheel, one of the last enterprises in Boar’s Head Yard was a

temporary refuge for fallen women, opened in 1860 in an initiative by the Rev.

Samuel Thornton of St Jude’s Church. There

‘sixty-four young women — mostly fallen, some in danger — nearly all from the

neighbourhood, have passed through the institution; … This excellent

institution is in some degree self supporting, the inmates earning money by

washing, mangling, and needlework.’

The whole of Whitechapel’s Petticoat Lane/Middlesex Street frontage was

cleared for road widening and its alleys for slum clearance in 1880–3 for the

Goulston Street Improvement.

Petticoat Lane Market

Contributed by Survey of London on Aug. 3, 2020

The origins of Petticoat Lane’s street market are obscure, and its antiquity

has been much exaggerated. John Strype, Stow’s successor as a London historian

who was born on Petticoat Lane, did not mention a market in the early

eighteenth century, nor is there any evidence to indicate a significant

presence of market trading in the street before about 1760. While the origins

of the street name do not lie in the clothing trade, for reasons already

given, there were clothing markets not far away by the time the name Petticoat

Lane came into use. This has contributed to historical conflations since the

nineteenth century. As ‘Petticoat Lane’ was a shorthand for prostitution

around 1600, so Houndsditch, to the west, was for clothing. Ben Jonson refers

to it in Every Man in His Humour, first performed in 1598: ‘Where got’st

thou this coat? … Of a Hounsditch man, Sir, one of the devil’s near kinsman, a

broker.’ By the mid eighteenth century a City triangle bounded by

Houndsditch, St Mary Axe and Leadenhall Street hosted a thriving market in new

and secondhand clothes, another Rag Fair, as on Rosemary Lane.

A feature of these markets was the ‘old clothes man’, a recognised type of

itinerant street hawker, always on the move, selling and soliciting stock, and

almost invariably Jewish. While there is no evidence of an established street

market in Petticoat Lane, there are hints that street trading of some sort

might have been taking place there by the 1760s, and that the traders were

Jewish. Whitechapel’s Paving Commissioners ordered the setting up of pitching

places or porters’ stands at the Whitechapel High Street end of Petticoat Lane

in late 1771. The stories that made it into the press were bleak. A man called

Levi, ‘a dealer of old cloaths’, hanged himself in his lodgings in Petticoat

Lane, Whitechapel, in 1766; Solomon Porter, ‘an old Cloathes-man’ who also

lodged in Petticoat Lane, was hanged for his part in a burglary in 1771; and a

gang of thieves conveyed their ‘Plunder to a noted Jew (a Receiver of stolen

Goods) in Petticoat Lane’ in 1778.

Reports of Petticoat Lane as thick with pickpockets suggest crowds if not

markets. In 1789 a public meeting called on magistrates to assist in

‘extirpating a notorious gang of thieves and pickpockets, who have long been

suffered to annoy and plunder the peaceable inhabitants of that neighbourhood

… Petticoat Lane is a very considerable thoroughfare … and certainly would

become more so were it rendered safe for the public to pass and repass.’

The mutable and mobile character of the area’s street markets is evident from

accounts of prosecutions of traders in Cutler Street, leading east out of

Houndsditch towards Petticoat Lane. In 1820 ‘Four old cloathsmen were charged

… with obstructing the highway, and establishing an old cloaths market in

Cutler Street, Houndsditch … from two o’clock until four each day, the street

was blocked with Jews and old cloaths … as soon as [the dealers] were moved

from one end of the street they were seen crowding together at the other, and

their baggage was all spread upon the pavement with the greatest speed.’

The market in what was already becoming Middlesex Street may have arisen as a

further spilling eastwards of the Houndsditch clothes market.

Laxness in use of the name ‘Petticoat Lane’ does not help clarification. In

1839 it was reported that: ‘The origin of the term “Rag Fair”, held in

Petticoat Lane, as Cutler Street is called, can easily be traced to the

commodities exhibited for sale.’ Cutler Street and Harrow Alley were

perhaps the conduits by which the clothes market did become established in

Middlesex Street, but quite when is hard to say. In 1830, a report of a court

case (written entirely for comic effect) related the theft in ‘the Market in

Petticoat Lane’ of ‘a pair of inexpressibles, value 2_s_’. The wife of the

accuser, Moses Levi, described the market: ‘Petticoat Lane Exchange is

conducted with the greatest regularity – five or six hundred people jostle one

another about all day – that she considered quite regular – (Laughter.)’

After this date reports of the market in Petticoat Lane increase, featuring

stolen goods and general sharp practice, usually couched in comic terms that

rely on Jewish and, sometimes, Irish stereotypes.

Henry Mayhew supplied much greater definition in 1849. His colourful

description, widely quoted, explains the topography of Petticoat Lane,

indicating that it did, inter alia, occupy ‘Petticoat-lane proper’

(Middlesex Street): ‘Petticoat-lane is essentially the old clothes district.

Embracing the streets and alleys adjacent to Petticoat-lane, and including the

rows of old boots and shoes on the ground, there is perhaps between two and

three miles of old clothes. Petticoat-lane proper is long and narrow, and to

look down it is to look down a vista of many-coloured garments, alike on the

sides and on the ground.’

Mayhew’s full account goes on to illustrate the difficulty in distinguishing

between the expanding street display of shops and a market with fixed hours of

operation, stall-holders operating from barrows independently of shops.

Hierarchical distinctions were made between shops, street traders with fixed

stalls, and itinerant vendors, pedlars and hawkers, who traded on the hoof.

While there had been some increase in the numbers of poor Irish immigrants in

the old-clothes trade, the itinerant vendors remained predominantly

Jewish.

Petticoat Lane’s status as a ‘Sunday market’, arising from its Jewishness,

became a focus of attention in the 1850s. Henry Ker Seymer MP reported that in

Petticoat Lane there was a ‘regular fair’ on Sundays between eleven and one

o’clock. He argued that ‘the violation of order and decency which there

prevailed’ meant that it should be suppressed. A fellow Tory MP, Robert

Carden, agreed, having visited on a Sunday morning and found ‘an assemblage of

some 10,000 or 12,000 people’. A difficulty was that half of the street was in

the City, half in Middlesex. It became apparent that for the City, the market

had become ‘almost a legalised nuisance’, tolerated ‘in order that they might

get rid of a similar nuisance which at that time existed in more important

thoroughfares’. It was also pointed out that it was invidious (and

implicitly anti-Semitic) to single out Petticoat Lane for condemnation when

trading was going on elsewhere on Sundays. Daniel Samuel of 32 Middlesex

Street (on the City side) explained: ‘if you would please come into Petticoat

Lane on Saturdays you would see the Sabbath kept, – the closing of all shops,

a cessation of all business.’ Further, for the poor, who mostly worked

six days a week, Sunday was often the only day for food shopping. George

Gordon of the National Sunday League wrote in support of the Petticoat Lane

traders and against the anti-Semitic grain, though perhaps as idealising as

others were scornful: ‘I saw nothing objectionable in this poor man’s bazaar

not the least violation of the peace … This unassuming locality is free from

the fashionable vices of adulteries, murders, and robberies … In certain parts

I have seen jewellers, &c, expose their valuables for sale, which at first

made me tremble for their safety; but such is their confidence in the sterling

honesty of the unwashed multitude that the religious and moral characters of

Duke-street, Houndsditch, and Middlesex Street are beyond reproach.’

Petticoat Lane market continued, with occasional increased police presence,

and by 1871 not just on a Sunday. A reporter then estimated vendors to number

around 700 and the press of customers, ‘from all parts of London’, at 10,000.

For a non-Jewish readership, the repeated tropes were the cheapness of goods,

the presence of criminals and the ‘foreignness’ of vendors and customers:

‘This Sunday morning spectacle … is one of the most sickening of all the

unadvertised sights of London. … the behaviour of those who congregate here is

a ruffianly swagger, while the constant din serves only to remind you of a

Jew’s quarter in a continental town’.

In 1880, a visitor detected that Petticoat Lane was not as busy as it once had

been, and that more of the clientele was not Jewish. But the market was

about to receive substantial boosts. Road widening at the south end made an

immediate difference to available space and then there was the impact of mass

Jewish immigration from the Pale of Settlement following the pogroms of the

early 1880s. When Charles Booth embarked on his exhaustive study of the Life

and Labour of the People in London in 1889, he began in the East End, just as

the Whitechapel murders (Jack the Ripper) generated wider fascination. The

descriptive tone is little different from that of the previous forty years –

‘a medley of strange sights, strange sounds, and strange smells’, but this

account provides a clearer sense of the street topography, ‘lined with a

double or treble row of hand-barrows, set fast with empty cases, so as to

assume the guise of market stalls. Here and there a cart may have been drawn

in, but the horse has gone and the tilt is used as a rostrum when the salesmen

with stentorian voices cry their wares’, and the goods on offer, the ‘cheap

garments, smart braces, sham jewellery, or patent medicines. ... Other stalls

supply daily wants – fish is sold in large quantities – vegetables and fruit –

queer cakes and outlandish bread.’ It also suggests again that the demography

was changing: ‘In nearly all cases the Jew is the seller, and the gentile the

buyer; Petticoat Lane is the exchange of the Jew, but the lounge of the

Christian.’ Booth testifies as well to a further eastwards shift, with mention

made of market stalls in Brick Lane, and the animal market in Sclater

Street.

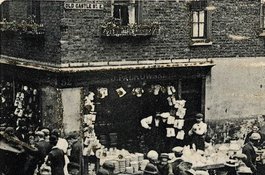

The renewal of the 1880s is also evident in a report on London markets from

1893, which stated that Petticoat Lane ‘is probably the largest street market

in London’, but also that in ‘its present condition the market is not more

than about 10 years old: before that time there were not more than a few

stalls in the streets: but of late years since the great influx of Polish and

Russian Jews it has greatly increased. The market is continuous, but most

business is done on Sunday mornings, Friday afternoons, and the days preceding

Jewish festivals.’ The report makes clear the move away from clothing to food.

Of 335 stalls, only 52 dealt in apparel, broadly interpreted – boots,

clothing, haberdashery and hosiery. Vegetables and fruit (59 stalls), poultry

(30), fish (55) and fruit only (61) were by far the most numerous. Shopkeepers

occupied thirty-five stalls.

Subsequent accounts of the market augment emphasis on brightly coloured

exoticism with a sense that many in the market were recent arrivals who did

not speak English. An unusually sympathetic reporter for The Queen in 1895

found that she could ‘converse freely’ in German with the Yiddish-speaking

traders. She took a particular interest in the food stalls, the ‘enormous

gherkins, in tubs of salt and water … Dutch herrings in tubs’, the ‘Jewish

cakes, including the thin Passover cakes; enormous brown and white loaves … or

a hot dish of dried peas and cabbage’, and the perennial East End favourite,

‘stewed eels in jelly’. Hebrew books attracted her attention, as did a kosher

butcher. Of the people, she concluded: ‘They were in many cases the poorest of

the poor, yet were orderly and even deferential as we passed, answering our

questions politely, and rather pleased than otherwise at our interest in their

wares … Petticoat-lane on a Sunday morning is intensely interesting. … these

people, with their own tongue, their own religion, their own manners, and

their own customs, are a living, breathing part of this great

metropolis.’

By this time, the appearance of Middlesex Street had greatly altered,

following the clearances of the 1880s and the building of Wentworth Dwellings,

Brunswick Buildings and shophouses and warehouses fronting Middlesex Street.

Houndsditch had become wholesale, Petticoat Lane retail. Occupancy of the

shops lining the streets had changed. Where clothing had predominated, by 1902

it was ‘now only a secondary business, there being only six clothes shop in

the Lane. … the beginning of it is occupied by dealers in light refreshments,

consisting of hokey pokey, wally wallies, hot peas, whelks, cakes of various

kind, hot drinks and cold drinks, stewed eels, sweetstuff, fruit, fried fish,

apple fritters, trotters, and many other cheap luxuries. Next is an exhibition

of moving pictures!’

The first decade of the twentieth century saw a number of threats to the

market’s future. The developer Abraham Davis built a ‘Jewish Bazaar’ complete

with kosher slaughtering facilities at what became Hessel Street market in

Stepney, then in 1906 tried unsuccessfully to create a new market for

Petticoat Lane traders on the south side of Fashion Street in

Spitalfields.

The Aliens Immigration Act of 1905, a reaction to recent Jewish immigration,

passed despite opposition. But even some of its opponents wanted Petticoat

Lane’s Sunday market closed. A bill to limit Sunday trading, others argued,

would mean ruin to the market’s ‘2,000’ traders and ‘10,000’ shoppers, many of

whom, paid on a Saturday evening, were reliant on Sunday shopping. The bill

failed repeatedly in 1906 to 1908 and clauses limiting Sunday trading were

dropped from the Shops Act of 1911. Petticoat Lane carried on.

Redevelopment on the City side of Middlesex Street in the 1920s and 1930s

still did not dislodge the market. It was said to have had, ‘a great fillip

since the war’, and the old stories of colour and crime persisted: ‘It used to

be jokingly said … that if you missed your purse or handkerchief at one end of

the Lane, you would find it for sale at the other!’ Food continued to

fascinate: ‘You can get fritters done to a turn – you see them emerge from a

tank of boiling fat in a compact little kitchen on wheels. All the improvised

“eat shops” do a roaring trade, and eels, winkles and every form of mollusc

are greatly relished.’

One enduring presence in Petticoat Lane market was Tubby Isaac’s jellied-eel

stall. This stood at the bottom of Middlesex Street from 1919 and later in

Goulston Street until it closed in 2013. Tubby Isaac was the nickname of Isaac

Brenner (1893–1942), Whitechapel born. He ran his stall in Petticoat Lane for

twenty-one years then emigrated to the United States in 1940, working his

passage as a ship’s cook. Tubby Isaac’s or Isaacs, as the stall came generally

to be known, was taken over by Soloman Gritzman (1908–1982), said to have

worked on the stall since it opened when he was aged eleven. Gritzman ‘became’

Tubby Isaacs, in Goulston Street, certainly by 1957, where the stall remained,

and for some years in the 1960s at the south end of Middlesex Street.

In 1928 Petticoat Lane market achieved official status when Stepney Borough

Council brought in licensing, and in 1936 it received further protection under

the Shops (Sunday Trading Restriction) Act, whereby Jewish shopkeepers and

stallholders who did not trade on a Saturday were permitted to trade on a

Sunday till 2pm. But that same year stallholders had to fight off an attack by

youths, ‘said to be Fascists’. The market still does not trade on

Saturdays, though the religious rationale has long since lapsed.

Substantial Blitz damage in 1941 destroyed buildings at the south end of

Goulston Street and Middlesex Street, and parts of Wentworth Dwellings. As a

consequence, a large extra trading area opened up in the cleared site between

Goulston Street and Middlesex Street. A sign of the extent to which the market

was thriving in the 1950s was the expansion of the Tubby Isaacs business. By

1957 there was an additional stall on Goulston Street, outside 133–137

Whitechapel High Street. The Middlesex Street pitch was used until road

widening in the late 1960s made it less salubrious. Soloman Gritzman

continued the jellied-eel business until around 1976 when Ted Simpson took

over, in turn replaced by his son Paul (b. 1964) in 1989. The stall also

served typical East End delicacies of winkles, cockles, prawns and mussels,

augmented by hamburgers by 1965, latterly even oysters, which attracted

professionals from the City. The business used an open-sided stall that could

be rolled into storage. By the early twenty-first century there was a more

compact towable fast-food trailer, with a counter along one long side and

boards that fold up in transit. ‘Branch’ seafood stalls operated in

Walthamstow from the 1980s until 2012 and in Ilford and Clacton in the early

twenty-first century. By 2008 another food van had pitched up opposite Tubby

Isaacs, selling halal burgers and hotdogs.

There were reports in 1964 that ‘the Lane will soon be under cover’, with

redevelopment of the bomb site underway. Cromlech House (see below) did

provide an open covered area, mainly for the storage of barrows and stalls,

and Mike Stern, long-standing President of the Federation of Street Traders’

Unions, was quick to point out that the covered section would provide space

only for ‘a limited number of unlicensed traders’ on the east side of

Middlesex Street and that the ‘building will not remove the colour or

attractions from the market’.

By this time the rhetoric of journalist visitors to Petticoat Lane tended to

centre not on ‘foreignness’ but on bargains and lively Cockney patter – ‘Most

stall-holders are quick-witted cockneys, with an entertaining spiel whether

the product interests or not.’ The imputation that goods were of dubious

provenance endured, and was not wholly imagined. Stolen goods – bicycles seem

to have been particularly popular – did turn up in Petticoat Lane. A mark of

the nostalgia around the idea of ‘the Lane’, the commodification and

mythologizing, was the opening in 1968 of ‘Cockneyland’, an indoor market-cum-

museum of ‘East End Life’ at 88 Middlesex Street, just north of Wentworth

Street in Spitalfields, run by traders Jo and Jack Josephs.

An Illustrated London News correspondent noted the changing demography of

Petticoat Lane in 1968: ‘The salesmen’s faces betray a variety of origins,

French, Jewish and Asian’, reflecting, at least as regards ‘Asian’,

immigration from Pakistan, especially East Pakistan (later Bangladesh), that

had been going on since the late 1950s. Cockneyland, however, had fallen by

the wayside by 1974. The pace of changing demography accelerated from the

1970s with the departure of most of the Jewish stall-holders and their

clientele, mostly to London’s Essex edges.

The process of transformation was gradual. Bilal Haq, who has worked in the

textile trade on Wentworth Street since 1983, has recalled how, ‘This whole

area was populated by Jewish people, they know the business and I [was] …

partnered with them [for] ten-fifteen years. I learned my way with them.’ It

is no longer evident, but the connection persists. His ‘suit shop was opened

in 1972. Jewish-owned, yes. They still own the building. It’s a corner

building. I mean I’m just paying the rent, basically’.

The market, for more than a century the target of official disapprobation,

received encouragement from the 1960s. Storage space at Cromlech House was

supplemented in the renovated Wentworth Dwellings (Arcadia Court) in the early

1990s and then in a building conversion for London Metropolitan University in

Goulston Street. In 2005 concertina gates, with mandorla shapes composed of

stainless-steel tubing and a panel announcing ‘Petticoat Lane’, were installed

at the east end of Wentworth Street to close the road to vehicle traffic

during trading hours.

However, there is a suspicion among local traders with a long connection to

the area that gentrification and the financial rewards it offers to local

authorities may soon finish off Petticoat Lane. Paul Simpson, the owner of

Tubby Isaacs, closed the stall in June 2013. ‘I’m the last one ever to do this

… The business isn’t what it was years ago … All the East End eel stalls along

Brick Lane and the Roman Road have closed – it’s a sign of the times.’

This message was echoed in 2019 by Mark Button of Barneys Seafood, originally

run by Soloman Gritzman’s brother, Barney Gritzman. His premises in Chamber

Street were sold in that year for development as an apart-hotel, the stall in

Petticoat Lane having closed years earlier: ‘Sadly, with the red routes, no

parking, double lines, no taxi drivers allowed to stop, changing it all back

to a two-way system from one way, the Congestion Charge, all the things which

put people off of coming … it slowly killed the trade.’ He will continue

making jellied eels, probably further out in East London.

Bilal Haq dates decline of the market to the mid 1990s, blaming some of the

same factors as well as poor facilities (especially the closure, as is

typical, of the public lavatory) and Tower Hamlets Council’s enthusiasm for

subcontracting social housing to allow lucrative private developments. Like

many Jewish traders before him, he has moved out to Newham.

‘Nobody is here … Five, six o’clock, nobody … only a few bars privately owned

... Apart from that, nobody. It is scary. If you even come about seven, eight

o’clock, it’s scary. [In] ten years time, it will be untouchable, this area.

Even to get a property in terms of lease, it will be untouchable. … This area

is going to go up, that’s what I believe … I’ve seen the way the whole area is

getting changed. It’s happening for good but some of our small businesses are

getting hit.

… I hope somebody comes out and says, “Look, we want to keep some of the

heritage”.’