A unique footprint

Contributed by Bryan Mawer on April 11, 2018

Tucked away in the archive of the late Bristol sugar researcher Mr I. V. Hall

at Bristol Archives is a simple plan, dated 1856, of the sugarhouse generally

listed as 27 Great Alie Street. For the most part it was owned by the

Craven and Bowman families and was built among the other refineries in Alie

Street, Duncan Street and Buckle Street (where my 4xgt grandfather learnt his

trade), all packed in around St George's German Lutheran Church.

Owing to its unique shape, the footprint of the establishment, then named

Craven & Co., is easily spotted on the Horwood map of the 1790s. Many

London sugarhouses had accommodation for the owner, or the manager, as well as

for some of the men (useful in case of fire at night). While the refinery

itself was usually a series of large, tall, rectangular buildings, the

owner/manager's dwelling varied both in shape and location. In this case the

dwelling had a prominent semicircular dining room.

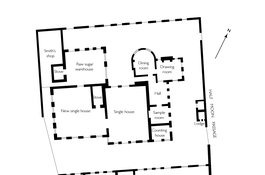

The ground plan shows: the main refinery site 129ft x 143ft; centrally two

adjoined refining buildings, the original about 40ft x 30ft, the new one about

40ft square; a raw-sugar warehouse and a smiths' shop; the owner's/manager's

dwelling with semicircular dining room, drawing room and hall, along with

sample room and counting house, all attached to the original refining

building; about 20ft to the south two warehouses, and a scum house.

Immediately south, and outside the main area, was a water tank, and south of

that the four houses nos. 30, 31, 32, 33 on Great Alie Street, which are

marked as belonging to the Craven estate and may have been occupied by

workers.

The sugarhouse would appear to have been built around 1785 and was still

refining in 1865, though under different ownership. The 1851 census shows it

employing 170 men.

The sales notice in The Times in 1867 informs us that the refinery comprised

a sugarhouse of six working floors, fill house and pan room, strongly timbered

and supported by iron columns, two stoves, sugar warehouse, retort house, two

chimneys, engine and boiler houses, yard, charcoal room, brewery, men's

dwelling house, detached offices, manager's residence, three dwelling houses

at 28 and 29 Great Alie Street and 16 Somerset Street, and a deep well giving

a constant supply of pure water. But the end was in sight for sugar

refining in the East End and the auctioneers wrote: 'The premises are well

arranged as a sugar refinery, but the large area covered by the property, and

the scarcity of freehold land in so central a situation, lead to the

conclusion that, by the clearance of the site and the erection of warehouses

or buildings suited to the modern requirements of trade, a very profitable

return for the investment of capital would be ensured.'

From Buckle Street to Camperdown Street and sugar refining to a data centre

Contributed by Survey of London on May 6, 2020

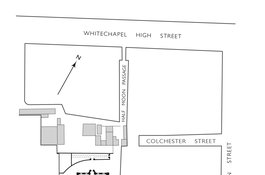

Alie Street’s northern hinterland back to what is now Braham Street, all

densely built up from the first years of the eighteenth century, was a place

that long maintained an industrial and working-class character. What is now

Camperdown Street was formed as the west end of Buckle Street, linking through

to Half Moon Alley and named after Edward Buckley (1656–1730), a wealthy

citizen brewer whose business was in Old Street and who had residences in St

Giles Cripplegate, St Margaret’s Westminster, and Putney. He was one of

several brewers to invest in Nicholas Barbon’s Fire Office around 1681, he

acquired an estate in St Margaret’s in 1682 where he became entangled with

Barbon’s development of Charles Street and Duke Street. He inherited both the

brewery and the Whitechapel property from his father, also Edward Buckley, in

1683. He had bought the Whitechapel estate from Thomas Neale a year earlier,

Neale having initiated and then backed out of developing what had been garden

land. Some work might have started under Neale, but it was the younger Buckley

who oversaw the laying out a grid of roads including Buckley (soon corrupted

to Buckle) Street and Colchester Street (later Braham Street) and saw to it

that the area was drained and built up by the 1690s. Buckley granted long

leases, including of ninety-nine years, as to Timothy Salter, a Whitechapel

bricklayer.

In 1789 Buckley’s son, Edward Pery Buckley, sold the estate to James Green

(anglicised from Laverdure), an enterprising Brick Lane bricklayer, who held

the property jointly with Matthew Darby and William Darby, the sons of Vice

Admiral George Darby (_c._1720–1790). By the end of the 1790s, Buckle Street

was known as Duncan Street, probably in homage to First Viscount Duncan

(1731–1804), ennobled for his famous victory at the Battle of Camperdown in

1797. As Captain Adam Duncan he had from at least 1779 served alongside George

Darby. The street was renumbered and renamed Camperdown Street in 1921.

Further north on the present line of Braham Street, Quiet Row or Were Row was

a short westwards continuation of Colchester Street that was renamed Nelson

Street around 1810, then Beagle Street in 1893, and much enlarged as Braham

Street when the Gardiner’s Corner gyratory system was formed in the 1960s.

Sugarhouses and other early buildings

A cluster of sugarhouses took shape around the west end of Buckle Street in

the eighteenth century. The most significant of these refineries was on the

west side of Half Moon Passage, standing free amid open space with a deep well

and a good water supply. The site is now that of 6 Braham Street.Thomas Budgen

(1705–1772), of a Surrey landed family yet apprenticed into the London sugar

trade in 1719, appears to have established this sugarhouse in 1726 in which

year he would have completed his apprenticeship. A year later he married

Penelope Smith, the heiress of Daniel Smith (d. 1722), who had been Lieutenant

Governor of the Island of Nevis. Budgen held onto West Indies sugar

plantations until his death and amassed significant wealth. He commissioned a

self-congratulatory portrait by Joseph Highmore in 1735, by when others were

managing the Whitechapel sugarhouse. By the time Budgen became an MP in 1751

he had sold up and extricated himself from Whitechapel. From 1750 to 1784 the

Half Moon Alley sugarhouse was owned by George Crosby, who ran it in a

sequence of partnerships. Its local dominance seems indicated by the temporary

renaming of Half Moon Passage as Crosby Passage during this period. John

Craven acquired a lease from Crosby in 1787, then around 1800 purchased the

copyhold of the land. By this date, if not long before, the sugarhouse had

seven storeys. Attached to its east side since at least the 1740s was a large

dwelling house that by the 1790s had three storeys and a prominent north-

facing bow window. This property passed between the Craven and Bowman families

until at least 1856. For a short time in the 1860s it was in the hands of

Thomas Kirkpatrick and associates.The Cravens and Bowmans were closely

linked through marriage and by other local ventures, entering into other

partnerships at sugarhouses on Duncan Street and Nelson Street. Most of the

south side of Duncan Street had been redeveloped by the 1790s as a three-

storey refinery that was associated with the Cravens and Bowmans from at least

1806. These premises, which came to rise five storeys and to be known as

Bowman’s Russia or Russian Sugar House, for reasons unknown, consisted of a

fill house (in which semi-conical sugarloaf moulds were filled), a bastard

house (bastard sugar being light-brown sugar), a scum fill house, a cooling

room, and a filtering or clarifying room. They were destroyed by fire in

December 1838.

The buildings were replaced in the early 1840s by a row of nine modest two-

storey houses. In 1881 Charles Wollrauch, an Alie Street builder–developer,

put up a row of workshops to the rear behind small yards. He returned in 1886

to add steep attics, perhaps also for workshop use. The row housed families of

mixed Jewish, German and English origins. Further east, three early houses

were replaced around 1820 by a warehouse with an arched vault. By 1844 this

building was partly in use by John Leigh of Leman Street as a gun factory. By

1900 it was Cunningham and De Fourier’s meat-paste factory. It came down in

the 1960s and the houses followed around 1980.

Opposite, on the north side of Duncan Street, there was a further sugarhouse,

also present by the 1790s. Largely destroyed by fire in 1819 when it pertained

to Craven and Shutte, it was rebuilt and, as described in 1834, it rose seven

storeys with a three-storey warehouse adjacent. Yet another sugarhouse went up

at the west end of what was soon to become Nelson Street around 1800. It was

destroyed by fire in 1847 when it was held by Craven and Lucas. The oldest

sugarhouse, that on the west side of Half Moon Passage, was sold in 1867 and

converted for use as a gun factory, occupied until 1908 by John Edward Barnett

& Sons, established local gun-makers who had prospered as suppliers of the

Confederacy during the American Civil War. The attached large house was

separately held and used as a hotel.

To the north on the west side of Half Moon Passage, Joseph Geiger & Co.

had established a cigar factory around 1840 in a move from Leman Street. This

was taken over by Barnard Morris (1796–1880), a German immigrant, around 1847.

A son, Philip Morris (1835–1873), launched cigarette brands under his name

while the factory continued as B. Morris & Sons. It was rebuilt after a

fire in 1882, to plans by John Hudson, and the premises extended further west

almost to Mansell Street. Leopold Morris, Philip’s younger brother,

established Philip Morris & Co. Ltd, which was incorporated in New York in

1902. The firm later became Philip Morris International, one of the world’s

largest tobacco companies. The Half Moon Passage tobacco factory was rebuilt

again in 1910 to plans by Deakin & Cameron, but within a decade it had

closed.

Camperdown House and 6 Braham Street

The Jewish Lads’ Brigade was formed in 1895 on the model of the Boys’ Brigade

with the aim of productively channelling the energies of teenage working-class

Jewish boys, pursuing an agenda of ‘social work and social control’. In

endeavouring to engage the children of poor immigrants in edifying leisure

pursuits, the Jewish Lads’ Brigade was one of a number of youth groups that

were said to have ‘unmistakeably coloured … the whole tone and character’ of

Whitechapel. Its first decade saw expansion in both membership and

curriculum so that, by 1910, the Brigade had outgrown its shared premises in

Bucklersbury.

Determining that purpose-built headquarters would best serve the Brigade’s

needs, Max J. Bonn, a banker and philanthropist, commissioned Ernest Joseph,

the architect of other Jewish youth clubs in London, to find a suitable site

on which to build a spacious modern institute. Joseph recommended the

acquisition of the Half Moon Passage site that Barnett & Sons had vacated

in 1908 and set about designing a Jewish youth centre. Camperdown House was

built in 1912–13 by Dove Brothers and W. Laurence & Son and opened by

Viscount Milner. It was a large complex with a grandly classical façade to

Half Moon Passage and a footprint roughly consistent with that of the

preceding factory and hotel to provide spaces for physical recreation,

meetings and other social activities. It proved to be a template for later

Jewish social and sports clubs such as the Maccabi Centres. The main or front

block housed a large common room and offices on the ground floor. The first

floor accommodated games rooms, a library, committee room, dining rooms and

more offices, while the second floor consisted of a small hall, a band room,

dressing room and sitting rooms. To the rear a second block extended

westwards, abutting factories but with its north and south elevations

sufficiently freestanding to light a large barrel-vaulted auditorium with a

capacity of 970. Two further halls, a rifle range, a gymnasium and other games

rooms were in the basement. Taking the view that physical cleanliness

encouraged moral purity, the Brigade ensured that ample washing and toilet

facilities were spread throughout the building. Given its impressive size and

facilities, Camperdown House was never intended solely for use by the Jewish

Lads’ Brigade and rooms were let to a number of associated ventures, including

the Lads’ Employment Committee, the Hutchison Club, and the Association for

Jewish Youth.

The First World War took a heavy toll on the membership and funds of the

Brigade, and early optimism dissipated quickly. A proposal to convert the

assembly hall into a large boxing venue was accepted at the third time of

asking in 1933. The hall was also used for dances, as it had been previously,

and to show films. The Auxiliary Fire Brigade requisitioned Camperdown House

in 1939, and Stepney Borough Council took occupation of some offices in 1940.

Though the building was seen as the head and the heart of the Jewish Lads’

Brigade, the organisation did not return to its Whitechapel headquarters after

the war, many members having migrated out of the East End.Instead, in 1952 the

Territorial Army took a lease of the property, only vacating in 1973 after the

formation of Braham Street had exposed the north flank and when redevelopment

was envisaged. It was replaced in 1982–3 by a faceless shiny glass-box office

block designed by Trehearne and Norman, Preston and Partners, and built by

Wimpey Construction (UK) Ltd for Wingate Property Investments PLC and the

Norwich Union Insurance Group. For a time this building was known as Frank B.

Hall House, after the investment company that was its primary occupier.

Converted into a data centre in 1999 and operated by Level 3 Communications,

the building hosts trading platforms for financial institutions and brokers as

6 Braham Street.