English Martyrs: the heart of the community (by Cathy J)

Contributed by interviewer2 on Sept. 26, 2018

Five generations of our family have worshipped and attended school at English Martyrs, Tower Hill, and we are of German-Irish origin. Our grandparents were married there in December 1911. Our grandfather was baptised in the German Lutheran Church in Alie St, and he converted later to the Catholic faith. Our Mum and Dad - Jerry & Eva Bills - were also married in January 1941 in English Martyrs Church. Here is their story.

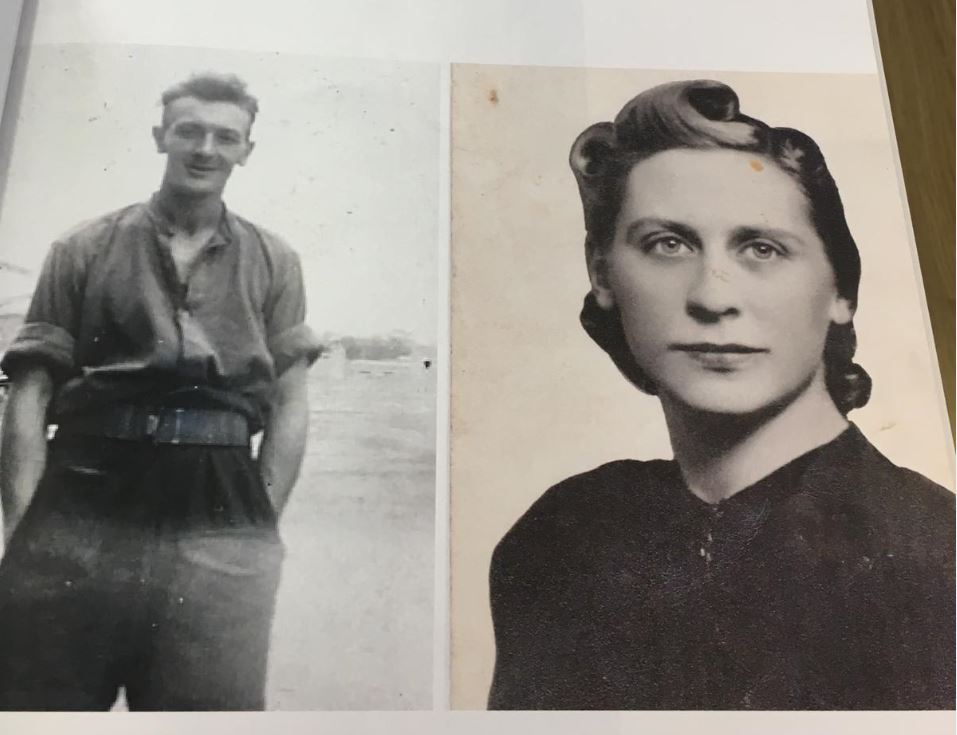

Jerry Bills and Eva Hageman in 1940

Eva Hageman married Jerry Bills (baptised Frances Bills but always known as Jerry) who also played in goal for the Tower Hill football team. They knew each other all of their lives and both went to Tower Hill School. They started courting in about 1940, and during June of that year Jerry was on the troop ship 'Lancastria' which was evacuating soldiers from France. Our Mum always told us that on the day of this event she had the most awful feeling and went to sit in our church. She spoke to one of the priests (at that time there was always at least 4 priests resident at Tower Hill) and because they knew Jerry was at sea somewhere the priest lit a candle in the Chancery Light in Our Lady’s Chapel. The candle was set in a boat hanging over the chapel. (The boat you now see on the there is a new one, the original being stolen back in the 1980s). My mother sat there with the priest for a while in quiet prayer. The ship evacuating the soldiers was hit and suffered the largest loss of life in one action every recorded. Our father Jerry could not swim but he made it back to England. Because of the loss of lives involved there was a news blackout put on this, but it was a story always well known in our family, and in the families of all those involved.

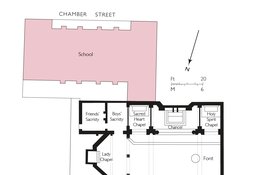

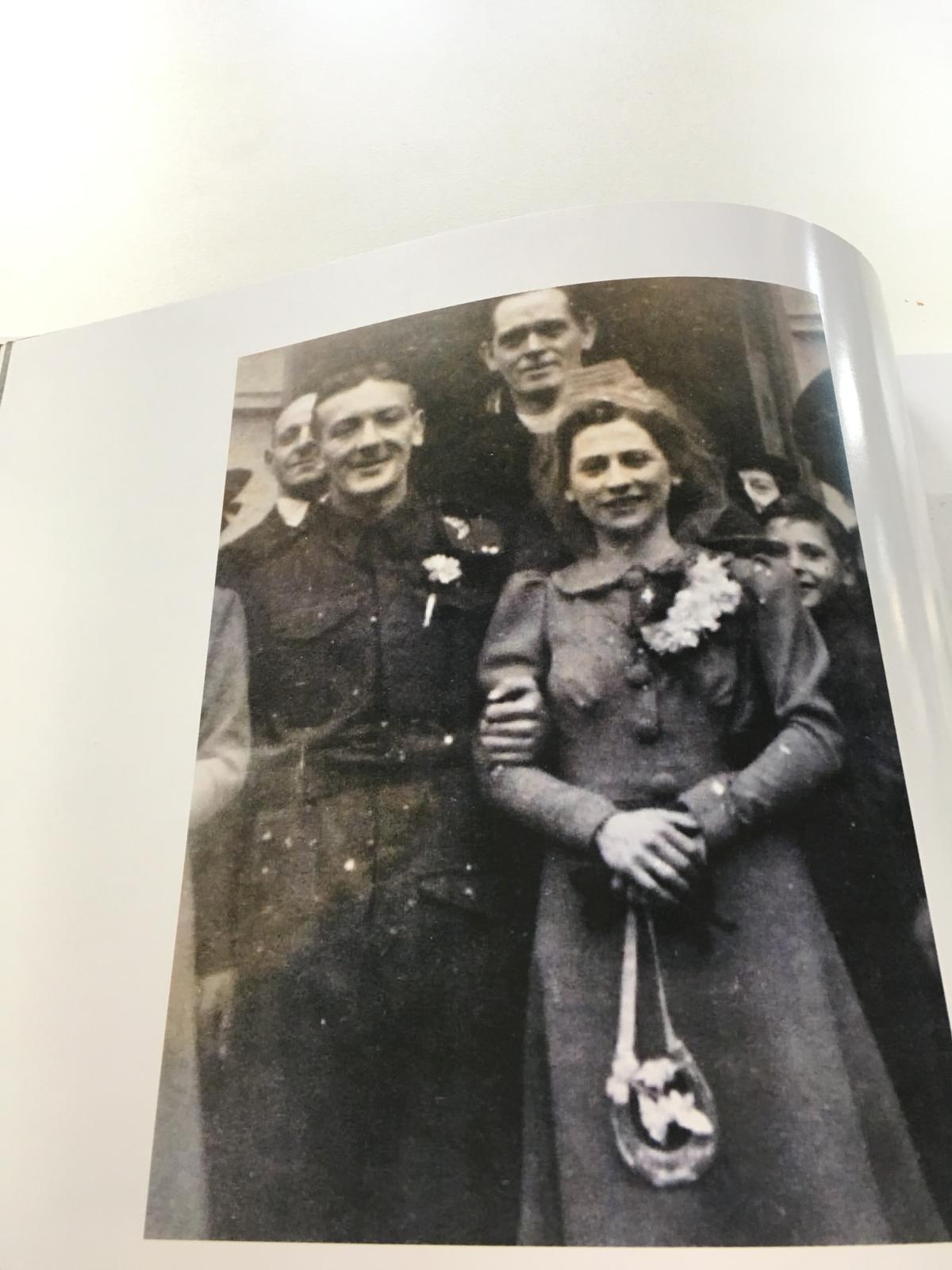

When our parents heard that Jerry he was being shipped overseas again, they decided to marry. The service was arranged for January 1941 and Jerry got a few days leave to return home. Eva, who was a dressmaker and made wedding dresses for a lot of girls, made herself a blue suit. On the day of the wedding English Martyrs Church took a direct hit from a 500lb bomb, which came through the roof and hit the pulpit, situated at the front of the church, quite near to where we now have the baptismal font. The bomb caused a lot of damage, but did not explode. Because of the timescale, it was agreed the wedding would go ahead but it was impossible to enter the church by the main doors. Instead our parents and family had to get in by going through the Presbytery (sited to the side where the Premier Inn is now), and enter the church through the Sacristy door, which opened out on to Our Lady’s Chapel. They were married there at Our Lady's Chapel by Father Gaffney as the bomb damage meant that they were unable to access the rest of the church.

Wedding day at English Martyrs, January 1941

The war ended and Jerry came home to meet his son Michael, by then three years old, for the first time. Our parents had three more children - Maureen (born 1947), Catherine (1954) and Jerry (1956). We all went to English Martyrs school, then located in Chamber Street; our children, and now our grandchildren went to the new school in St. Mark Street (opened in 1970), meaning that five generations of our family have been educated there. Our parents worshipped at Tower Hill all of their lives. Jerry always collected the Offertory at Mass (usually the Saturday vigil) along with Bill Rushmer. Eva cleaned the church until she became too ill. Both were buried from there, Eva in January 1984 and Jerry in July 1997.

To them Tower Hill (English Martyrs) was not just a place of worship, it was the heart of their community. This is no doubt true of all of that generation of Tower Hill parishioners as many, including our family, were either immigrants or the children of immigrants.

Memories of the oldest parishioner

Contributed by Survey of London on June 1, 2018

The oldest parishioner of English Martyr's Church was interviewed about his life in Whitechapel by Sarah Milne in early 2018.

"I was born in 1925 in Cartwright Street. I've lived almost 93 years in the same parish. I was born there, baptised there, went to school there, married there, and so on and so forth...and I'll get buried from there!

On my maternal grandparents' side I am Irish. I'm English on my paternal grandparents. Funnily enough I know far more about my Irish grandparents than I do about my English grandparents. Believe it or not, my Irish grandfather, Tom Penny, was born in County Cork in 1818. My mother was the youngest of their thirteen children, so I am, as far as I know, the only surviving grandson. Most of my mother's family...I grew up as a child calling people uncle and aunt, but when I got to know a bit more about the family, I realised they weren't uncle and aunt, they were cousins. There was such a lengthy time span you see. And dear old Tom, that is a story in itself. He was born in 1818, joined the British army in Cork in 1843, which I believe was one of the famine years, served twenty years in India in the army, he was discharged because he suffered a wound in the right thigh caused by a jiggle-ball, and he came back to Ireland and married my grandmother and as far as I can make out, they came to live in England in 1863. And they had several addresses in this local area. The strange thing was, he was a very pious Church of Ireland man, whereas my grandmother was a very pious Catholic, a very unusual arrangement. They married in Cork Registry Office, and he laid down the law that she could continue practising her faith but under no circumstances were any of his children to be baptised Catholics. So, they stuck to that arrangement until he died in, I think it was about...1905, when there were just two children left in the house, all the others had been married and gone off. The youngest being my mother, the next oldest sister Nell, and the story is that before they laid the old man out, the grandmother had the two kids round the church and baptised Catholics. All the rest of them were Protestants. They were baptised in English Martyrs in Prescot Street. My grandmother lost no time in doing what she always wanted to do...

My mother and father got married in Tower Hill Church. My mother wouldn't get married anywhere else! My father was Church of England as far as I know. I don't know a great deal about him. I was only five when he died. He died in December 1929, which was when the Great Depression started, the worldwide depression, which was a terrible terrible time for my mother because she had three children. I was the eldest at five, my next youngest brother was three and a half, and my youngest brother was a baby in arms, so it was a dreadful time for her, I mean there were no backup systems, no help at all, all that was available was parish relief. The system was that if people applied for assistance, they would come into the house and you had to sell anything that was not relative to everyday living, that was classified as luxury and that got sold off before you was awarded any help, you know? A terrible terrible time. And of course it was the time when there was mass unemployment, and when we were rolled down the ladder in terms of getting any employment was concerned, I mean the only thing available was domestic service, but that didn't occur in this area. So it was a very grim time, a very very grim time. My mum fought tooth and nail because she was almost being pressurized to give the three kids to the Crusade of Rescue, who looked after orphan children and the like. And she was well against it and she fought tooth and nail to keep us all, and a sterling job she did.

She did eventually...round about 1935...she managed to get a job with the local council as a bath attendant at Mile End, then it was the day of the public baths, I mean nobody, nobody had a bath in this area, nobody at all. It was a pretty hard job, the sort of thing when you went in it was a two class system, the working-, lower price was tuppence and then fourpence meant you had an extra towel or something, and first class was classified. There was a row of cubicles with baths in, and the attendant was outside with the handle controlling the water."

The draw of English Martyrs

Contributed by interviewer2 on July 3, 2018

Interview with a parishioner, 'V', on 29th June 2018

Parishioner V: I have lived in this parish and attended English Martyrs Church for nearly forty years. However, my family's connection goes much further back - to the late 19th Century, and the years when Tower Hill was developing as a parish. My maternal grandparents lived here: my grandfather was a non- Catholic, but he was baptised and converted to Catholicism. He and my grandmother were married in English Martyrs Church in 1893. They had seven children - one boy and six girls one of whom, Mary Wood, was my mother. The family was very poor. They lived in two main rooms; my grandparents slept in one of the rooms and my uncle slept in the other. At that time it was not accepted for boys and girls to share bedrooms, so for sleeping my mother and her sisters were farmed out to other parts of the family so as not to break the rule! In due course the whole family moved to live in the adjacent parish, St Mary and St Michael's, further east on Commercial Rd.

Interviewer 2: You told me that your mother attended the parish school of English Martyrs. How did that happen?

PV: Although we lived in a different parish, my grandfather always thought of English Martyrs as his parish. So he was determined to send all his children to English Martyrs school, which was the building attached to the back of the church, fronting on to Chambers St.

[NOTE: The school moved to its present location in St Marks St in 1970, and the Oblates recently converted it into a retreat centre, called De Mazenod House]

I2: Can you tell me a bit more about your mother's time at English Martyrs School?

PV: The school was run by the Holy Family Sisters, who often worked with the Oblate Order. In my mother's time the headteacher was Mother St Aidan. The nuns lived in a convent in Prescot St, which was eventually knocked down in the 1980s and replaced with the Premier Inn. My mother did all her schooling at English Martyrs. She was born in 1907, started school in 1912, and finished at the age of 14. After that she went into service in Highgate for a short time. But she was not happy there, and came back to East London, where she trained and worked as a book-keeper.

I2: Did you and your parents live and worship in the Tower Hill parish?

PV: No. My parents got married in 1934 and the family was brought up in the parish of St Mary and St Michael's. I was born and went to school there, not at English Martyrs. But we still had lots of connections here and kept in touch with friends my family had known in Tower Hill. The biggest reunion took place during the parish May processions, when everyone like us who had moved away would come back to Tower Hill and take part during the day. Then in the evening the bands would come out, and we all enjoyed meeting up. Finally, my parents decided that they wanted to return to live in the parish so I moved back with them in the early 1980s. They always joked that they had 'emigrated' to the parish in Commercial Rd, and that their true roots were here at English Martyrs. My mother really loved this parish and, like many parishioners, she had a particular love for the Lady Chapel.

Procession Sunday and the East End Exodus

Contributed by Survey of London on June 15, 2018

Interview with the oldest parishoner (OP) continued, including information from his daughter 'F'.

F: “When we used to have the outdoor processions...they were great. It was a lovely day. You used to have the procession and then later on in the evening the band would just come round and play all the old songs while the priest blessed the altars.”

OP: “You could describe it as the highlight of the year in parish life because you had the people who had moved away over the years invariably made a point of coming back. It didn't matter how long they'd been away, and if you'd met them wherever they'd gone to live, they always declared themselves Tower Hill people. They would never say they came from anywhere else.

The procession would go and do a tour of the parish, it was quite a lengthy walk really, especially for the small kids. And then they would come back to the church and there would be a short service of benediction, after which everybody went home and all the relatives who were visiting came to see and one thing or another. Then in the evening the priest would go around blessing all these altars and they'd be accompanied by a drum and [Irish] pipe band."

F: “They used to play all the old songs, it's a long way to Tipperary, Danny Boy and all that...”

OP: “Then we'd all go and have a good drink afterwards.”

F: “But sometimes before you went and had your drink, you'd had a little tipple of sherry or something indoors with the tea with the family, and then you'd come out to see the band and the priest and everyone would be dancing behind them and singing.”

OP: “It used to drive my missus mad getting five kids ready for the procession…"

F: “It was horrendous. She was very precise with everything and everything had to be just so. It was just crazy. But it was lovely at the same time…because Daddy was a Knight of Saint Columba…"

OP: “It was a great day, procession Sunday. It always took place round about June. In May they used to have the indoor procession for the May Queen, and I showed you pictures of my younger daughter when she was the May Queen.”

F: “People used to make altars on their window-ledges, altars in doorways [for procession Sunday]...”

OP: “It was basically [made of] a statue of some sort, it would either be our Lady or the sacred heart, a picture of the pope...Symbols of religion, of the faith...”

F: “Obviously with flowers…All the local streets would have them...”

OP: “Every street on the route would have them. We lived up on the third floor so my mother used to stick out the pope's flag. A yellow and white flag would go out her window.”

F: “They used to be brilliant days. The night before the procession everyone used to go round and look at people's altars. Some of them, they did them beautiful, but it didn't matter, it was all part of it. They used to have their candles alight, and all that, and in the square in the middle of Peabody's, there was a big block there that got bombed in the war…”

OP: “They'd all be disappeared by the Monday [the altars]…”

F: “…And the priest always used to pray on that spot [at Peabody’s] as well on procession Sunday. There was a lot of people that lost family in that block, there was an altar nearby there...”

OP: “The route changed slightly over the years. We used to leave the church and we'd go up Prescot Street, across the road into Hooper Street, across Lambeth Street, [up to Commercial Road] then down Christian Street and come back a little bit this way, and then Pell Street…Pell Street has gone now."

F: “We went over the Tower way first!”

OP: “No we went along Commercial Road first, then down Pell Street, then down the bottom of Thomas More Street, it was then called Nightingale Lane up until just before the war, to two council blocks that we felt belonged in our parish, so we did those and then we'd come back up John Fisher Street for the Peabody lot, and then Cartwright Street and we'd finish up on Tower Hill where they executed the Catholic martyrs, Thomas More and John Fisher. We used to come round this way, [but] when Pell Street disappeared after the war, it was considerably shortened because we'd lost so much ground you know? Pell Street had disappeared and we had quite a lot of people living down there.

These were the days when the great exodus to the East took place from the East End, to Dagenham. We used to go down and visit them...I was never tempted to move out. I can't tolerate suburbia in any of its forms. I've got no reason for it. I just thought I'm a city person and I've never had a desire to live anywhere else. Occasionally I went to visit some of the people who moved out there. I mean I have a sister in law living in Dagenham East at the moment. I’ve got a brother in law living in Hornchurch, I've got a granddaughter living in Buckhurst Hill. One of my own daughters is living in Beckenham, which is very very nice, but it's a bit upmarket. It's a question of horses for courses.”

My Home in Whitechapel

Contributed by Survey of London on Feb. 13, 2019

This is an extract of an account published in the Pall Mall Gazette in 1903 by the Dowager Duchess of Newcastle. The Duchess moved to Whitechapel to involve herself in the Catholic Social Union aimed at fostering community amongst working girls. Initially, she rented a property on St Mark's Street, but latterly moved to Prescot Street. Both premises were selected on account of their proximity to English Martyrs.

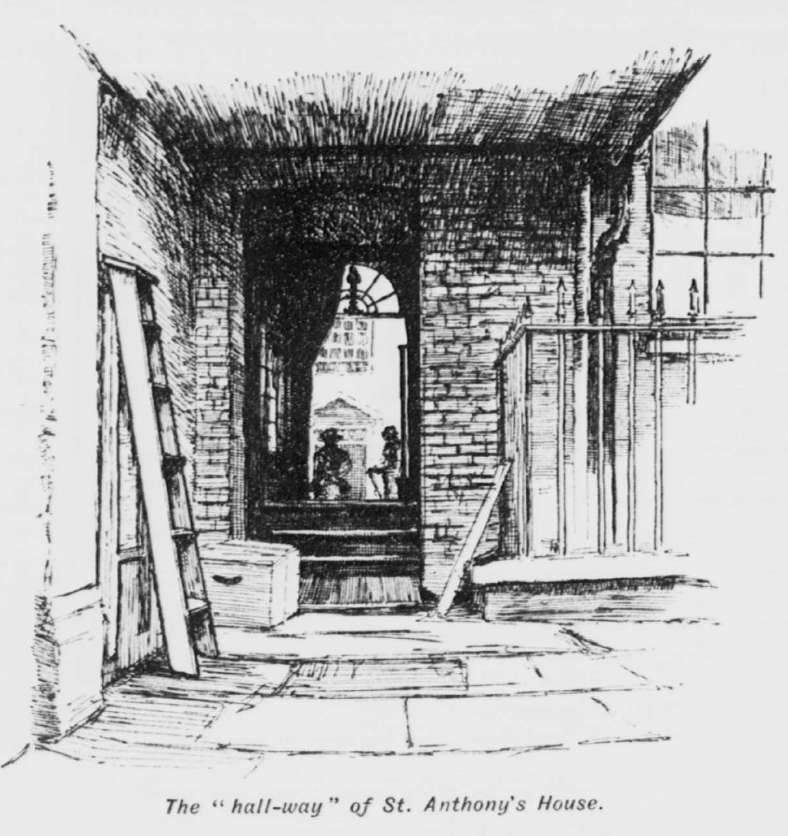

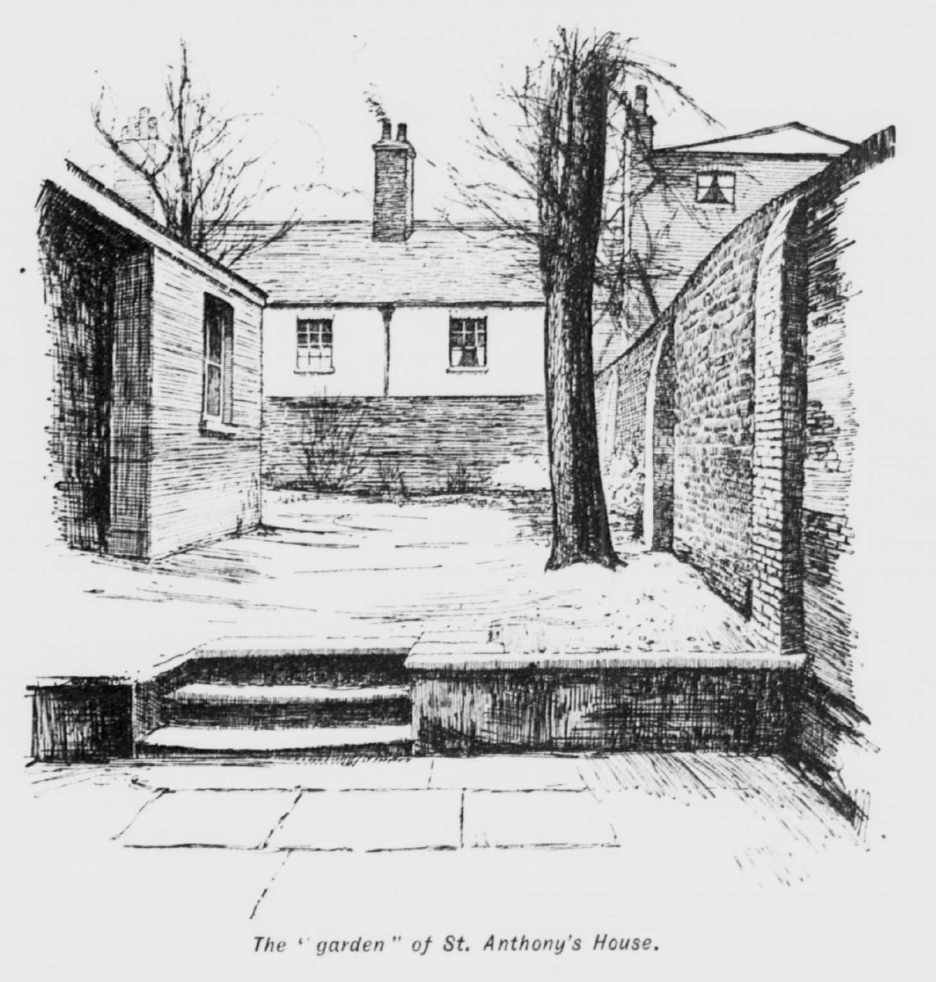

“After a while we started a Mothers’ Meeting, and opened a Boys’ Club. In 1896 the house [in St Mark’s Street] became too small as the number of workers increased, and I took a larger one, which we called St Anthony’s, in Great Prescot Street…The surroundings of my new home in the Whitechapel district of London are not without interest…

Many a house in the vicinity, now tenanted by the very poor, still shows signs of past grandeur. The inhabitants of this part of London are mostly waterside labourers, and depend for their daily bread on the ships that unlade and lade again in the many wharves and docks that line the river - a precarious living, and one which accounts for the deep poverty of most of our people. The better- to-do class are tailors and tailoresses who work for the City shops, earning more or less as trade is slack and brisk, but who can hardly hope to do anything more than live from hand to mouth, for the rents are excessive and the families generally numerous…

One of the most loveable traits of the Irish Catholics is their untiring devotion to their church. To them the church is their highest interest in life. Their homes may be squalid, but to the church they will give their last penny, and in it they feel at home, for all can point to some part - pulpit, statue, or altar - which was given by them and paid for with their hard-earned and badly-needed pennies… 'Many a shilling have I given towards building that church!’ another will say; or sometimes, ‘I have given many a brick for that church!’”