Former Outpatients Department, Stepney Way

Contributed by Survey of London on March 2, 2017

The north-west corner of the junction between Turner Street and Stepney Way is

dominated by the former Outpatients Department of the Royal London Hospital, a

substantial red-brick building constructed to designs by Rowland Plumbe in

1900–2. Plans to improve the outpatients department were conceived as part of

an ambitious rebuilding programme carried out under the auspices of the

hospital’s chairman Sydney Holland, 2nd Viscount Knutsford, whose fundraising

talents earned him the nickname, ‘Prince of Beggars’. By 1897 the

outpatients’ department had outgrown its basement accommodation. Earlier

attempts to relieve overcrowding had led to the transferral of the surgical

outpatients’ unit to the Alexandra

Wing in 1864–6, yet its medical counterpart had persevered

in rooms in the West Wing that dated from the 1830s. These

‘cramped, dark and badly ventilated’ basements were inadequate for the volume

of patients, which soared to as many as 1,000 in an afternoon. A number of

solutions were considered, including the feasibility of enlarging the existing

department. In the event, a donation from the shipbuilding magnate Alfred

Yarrow secured funds towards a new building. At its completion, the medical

and surgical outpatients’ departments were reunited in the largest building of

its type in Britain.

The former Outpatients Department from the south-east, photographed by Derek

Kendall in 2016.

A large chunk of the hospital estate, designated ‘Block M’, was taken for the

new Outpatients Department. The intended site, occupied by thirty-five early

nineteenth-century terraced houses, comprised almost an acre bounded to the

south by Oxford Street (now Stepney Way), Turner Street east, Green Street

(later Pasteur Street) north, and a terrace overlooking New Road west. The

complex was erected by the Bermondsey builder William Shepherd, also

contracted to construct a tunnel beneath Turner Street to connect with the

hospital. Early drawings indicate that it was intended to construct the

building in stages, deferring the second-floor lupus, photographic and

radiographic suites, yet the department was complete when patients were first

admitted in December 1902. Its formal opening was reserved for a royal

ceremony the following June.

The Outpatients Department would once have appeared in stark contrast in scale

and materials to neighbouring stock-brick terraced houses, though its large

footprint no longer seems remarkable due to later hospital expansion. The

Outpatients Department has retained its workmanlike appearance, with plain

red-brick walls punctuated by large windows on each of its three main storeys.

The brickwork is relieved only by artificial stone strings, narrow horizontal

grey-brick bands, and a practical glazed-brick plinth. The corners of the

building rise to sturdy square towers with top-floor tank rooms capped by

pyramidal roofs with ball finials. The former public entrance in Stepney Way

is adorned by a shaped gable with a gauged brick cartouche, now concealed

above a clumsy modern canopy. The entrance is positioned between robust stair

towers, with doorways designed as private entrances for the physicians and

surgeons.

Former public entrance to the Outpatients Department in Stepney Way,

photographed by Derek Kendall in 2016.

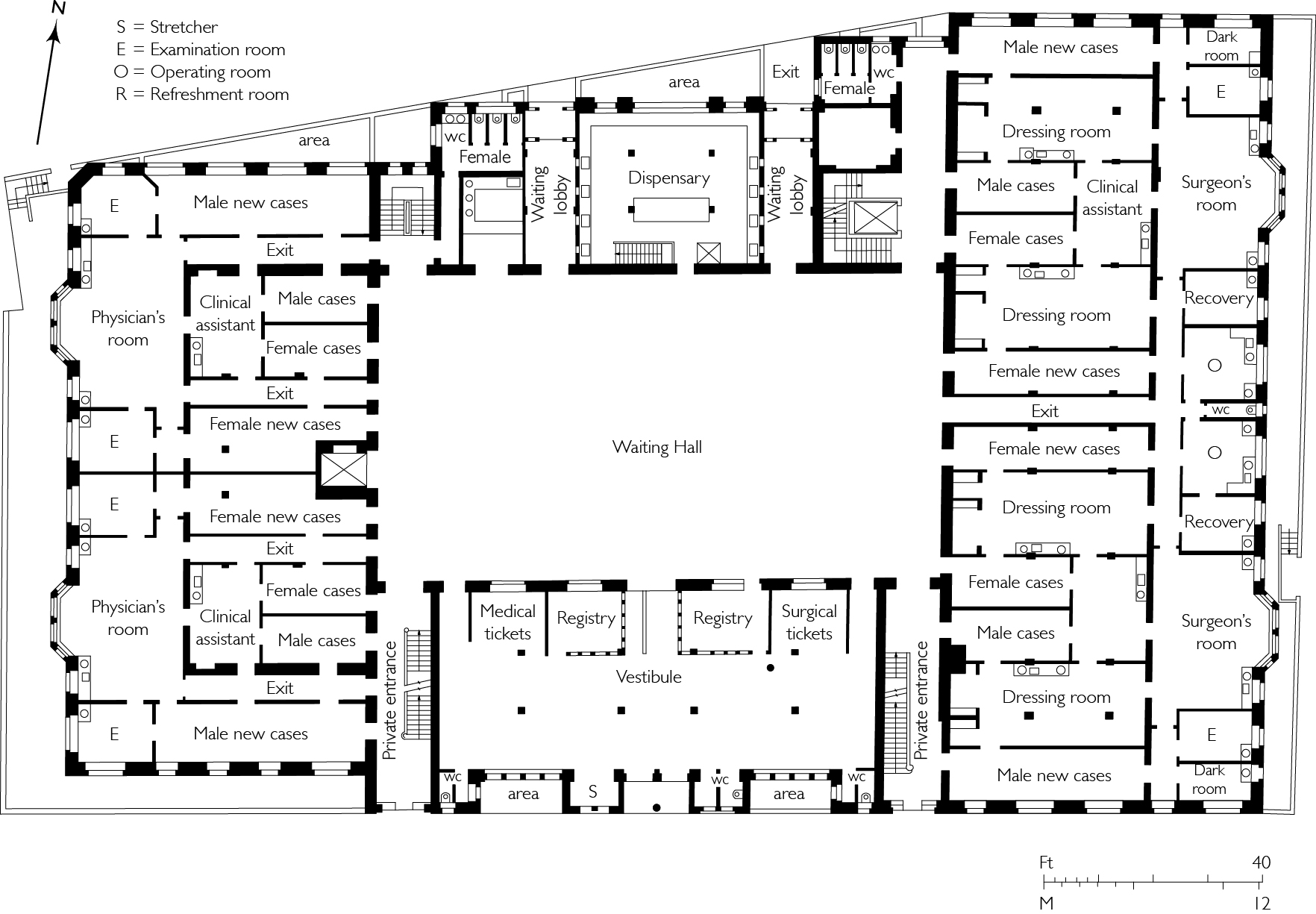

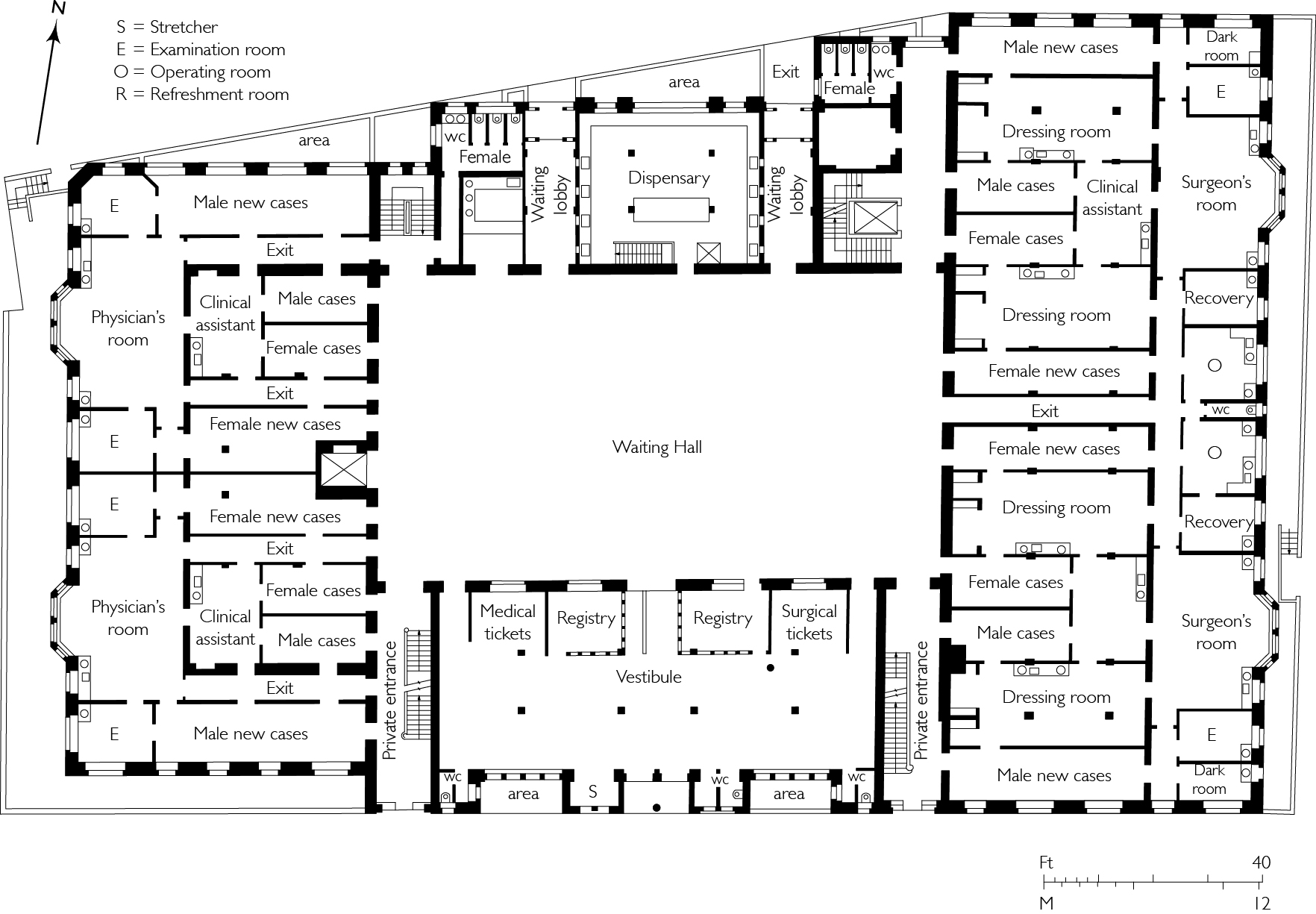

The Outpatients Department was planned with considerable ingenuity to ensure a

continuous and orderly flow of patients through the building, and the

separation of different types of cases. This sophisticated plan could only

have been accomplished through close collaboration with the hospital’s medical

and surgical staff. The public entrance opened into a vestibule that contained

a registration office for new cases and ticket offices for returning, or

‘old’, patients. At the core of the building stood a vast and airy waiting

hall that ascended to an open steel-framed roof crowned by a full-length

lantern. It was furnished with a refreshment bar, drinking fountains, and

uniform rows of benches designed to provide seating for 1,000 people. This

central hall was wedged between a surgical department to the east, a medical

department west, and a dispensary north. Plumbe’s utilitarian treatment

extended to these internal spaces, which were lined with easily cleaned glazed

walls and mosaic floors.

Ground plan of the Outpatients Department, redrawn by Helen Jones from a plan

printed in 'The Lancet' in June 1903.

The surgical department was formed of two ‘complete suites’, each containing a

surgeon’s office flanked by an operating room, a recovery room, an examining

room and a dark room. Waiting rooms for old and new cases of both genders

were accessed directly from the central hall. These narrow, top-lit rooms

communicated with dressing rooms, supervised by a clinical assistant’s office.

A similar arrangement was accomplished in the medical department, with two

suites formed of top-lit waiting rooms for old and new cases adjacent to a

clinical assistant’s office and examining rooms. The west end of each suite

comprised a physician’s office lit by a large bay window.

The dispensary was flanked by two waiting lobbies, where patients would

receive prescriptions before exiting to Pasteur Street. A large basement

laboratory directly below the dispensary, accessed by a lift and staircase,

produced medicine and drugs. In addition to this pharmaceutical laboratory,

extensive store rooms, a boiler room, isolation rooms and staff rooms, the

basement housed the bath department. This contained Turkish baths and

medicated baths, for immersion in sulphur, mercury and carbonic solutions,

along with rooms dedicated to the Tallerman treatment, a novel method of

administering ‘superheated’ dry air to relieve rheumatic disorders. Tyrnauer

hot-air baths were installed in 1909 for the treatment of similar

complaints.

Lupus patients receiving Finsen light treatment in the Outpatients

Department, photographed by Bedford Lemere in 1917. (Historic England

Archive)

The first and second floors of the building contained more specialist

departments. Their plans were arranged by a similar formula, with corridors

encircling the central waiting hall and light wells above the top-lit surgical

and medical rooms on the ground floor. An assortment of rooms for waiting,

consulting, operations and recovery skirted the perimeter of the building,

forming suites for each department. The first floor contained the aural,

dental, obstetric and massage departments, whilst the second floor was

dedicated to the ophthalmic, photography, lupus and electrical departments.

These specialist departments boasted the latest medical innovations, including

the use of Röntgen rays in radiography and the first Finsen lamp to arrive in

Britain. Named in recognition of its Danish inventor and Nobel laureate, Niels

Ryberg Finsen, the pioneering device emitted light radiation to treat lupus

vulgaris, a tuberculous skin infection once common in east London. The

hospital’s first lamp was donated by Queen Alexandra in 1900 and initially

installed in a single-storey shed located in the hospital garden. By 1909 the

lupus department was considered to be the finest of its kind in the capital,

with treatment machines for up to twelve patients powered by roof-top

generators.

Subsequent alterations to the Outpatients Department included a roof extension

built by W. Lawrence and Sons in 1909–11 to designs by J. G. Oatley, and

modifications to the X-Ray Department carried out c.1938 by local builders

Walter Gladding & Co. The building was remodelled in 1963, and substantial

layout changes effected in the ground-floor surgical and medical suites. The

building closed in 2012, when the hospital moved to its new

premises and was granted

immunity from listing in 2017.