A visit to Riyad's Marrakech Cafe in early 2018

Contributed by Ruhel_Ahmed on May 24, 2018

This is an extract from a longer piece of observational writing undertaken in 2018 by Ruhel Ahmed, a first year architecture student at the University of Westminster:

“There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city; people make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans”. Downtown is for the People, Jane Jacobs (1958)

The time is 5:42pm on a winter’s day and the temperature is near zero. It is reaching nightfall. Heading into Riyad’s Marrakech Café, a young girl, wearing a headscarf, holds the door open for me and smiles before she catches up with her family who had just left. Facing the street, through the large panes of glass, the clanking of silver cutlery can be heard behind me. The workers can be heard laughing hysterically behind the counter speaking in Arabic to one another. “I’m half Egyptian and half Moroccan” says a female voice behind me. As I glance back, a daughter can be seen speaking to her mother in sign language while the other chats with the waitress. The waitress politely asks for my order with a welcoming smile: a young Bengali girl perhaps working to fund her studies. The café, being lively and packed, means the door opens every thirty or so seconds with the sound of the cars’ engines outside, and the whooshing sound of the wind, growing and dying in rhythm with the door’s movement. Gazing out of the window, four large black bins labelled ‘COMMERCIAL WASTE ONLY’ lean against the brown brick wall on the building opposite. Some parts of the wall are covered with black boards which street artists to see as an opportunity to tag their names and make the street their canvas. The narrow yet busy two-way road is never seen empty. Parked cars line the street side closest to the café whilst other drivers squint at the yellow parking suspension sign attached to the lamppost, having just parked their car there. Boy-racers blast music through the sound systems of their blacked-out BMWs, Mercedes and Golfs. On the pavement a young Muslim lady pushes along her charcoal-black pushchair. Those escaping into the numbing weather protect themselves with fur-hooded coats, youngsters in their black puffer jackets and sagging jeans rush to get home from their colleges, a man carries his pink- clad baby girl in his arms, and students from the nearby secondary school struggle to carry their oversized black backpacks having left school late. A Deliveroo cyclist can be seen riding on the pavement heading towards Commercial Road and a couple of tourists look around in confusion in their coloured waterproofs and crammed backpacks. As the evening prayers finish, young teens and children travel home in their headscarves and religious clothing, more and more Muslims begin to emerge as they make their way to their next destination, bearded men carry their children and hold the hands of their little ones and Bangladeshi locals speak in their language to one another outside. Half of these people travel with their paper-blank faces as if following a routine normal to them. Others show more purpose, their heads held high, whilst some curiously look into the café to see if it’s worth eating in. As the daylight disappears so does the activity in the café and on the street. The deaf mother of the family behind me uses sign language to say goodbye to one of the café workers. And those finishing their tea prepare to leave the café.

It is now 12:40pm the following day. The transition from rush hour on one day to lunch time on another is barely noticeable. The café is just as busy as workers come out for their lunch breaks needing to be fuelled for the rest of the day. The whooshing sound of the passing cars and wind is still recognisable as the door continues to open and close in a regular pattern. The presence of Bangladeshis and Muslims of different nationalities is still distinct as they laugh amongst each other with friends and family inside the café. Conversations are much louder now: so loud that spoken words and sentences throughout the café mix to become unified mumbles. The clanking of metal against plates is now more apparent and the jarring sound of glass hitting the table only shows us that everyone here is eating well whilst enjoying the company of one another. The daylight shining through the window has resurrected what couldn’t be seen or enjoyed in the dark, such as the view of the street outside and its endless activity. The diversity inside café turns it into a community hub where people of all races and religions come together, not just in the same building but also on the same table.

The

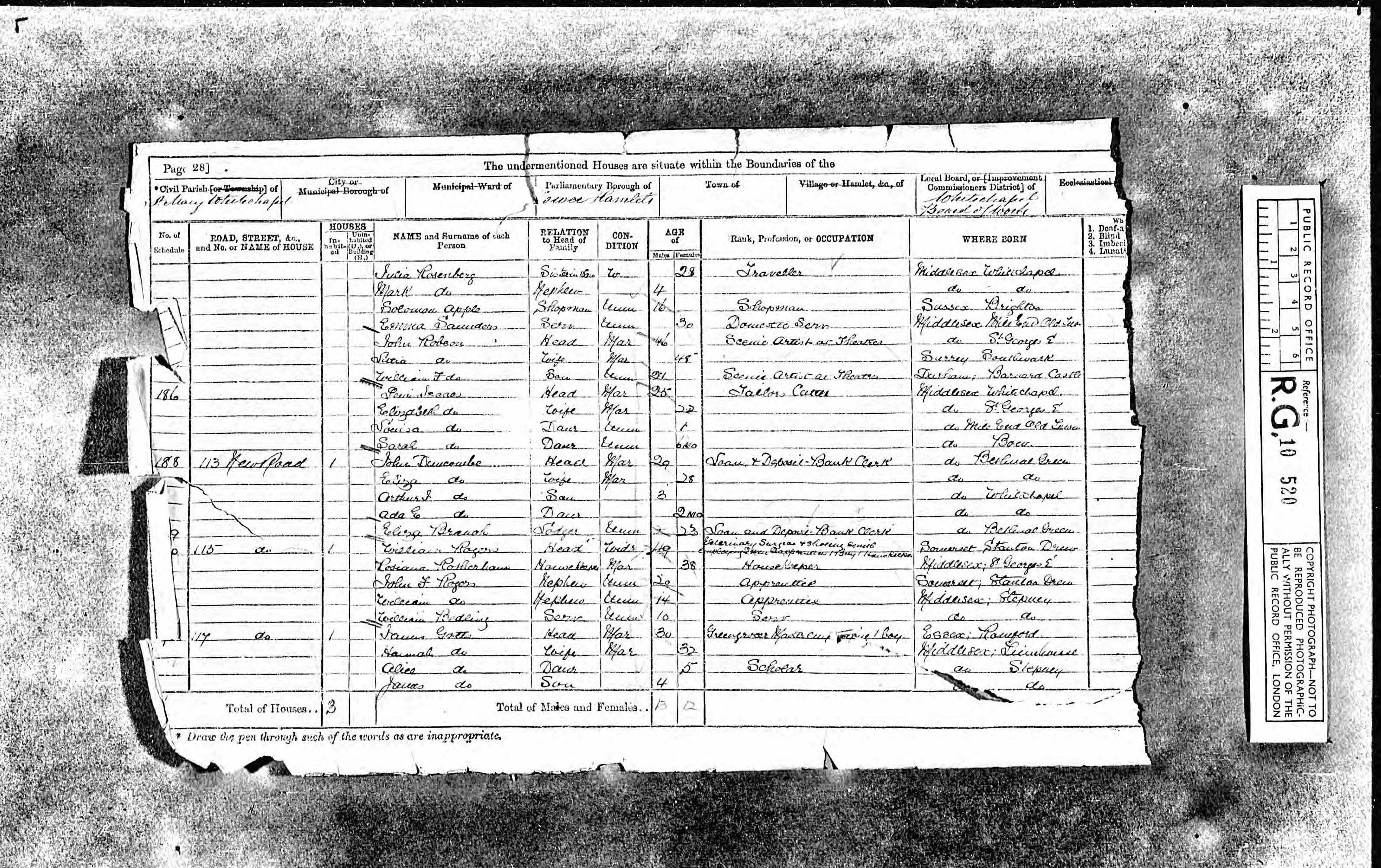

1871 census for 111 New Road, showing Louis Isaacs and his family a few years

before Esther was born there.

The

1871 census for 111 New Road, showing Louis Isaacs and his family a few years

before Esther was born there.