Fieldgate Mansions

Contributed by Survey of London on July 2, 2018

Fieldgate Mansions is a substantial complex of tenement dwellings of 1903–7.

In the 1790s Thomas Barnes had created a 10ft-wide alley between New Road and York (Myrdle) Street on this part of the London Hospital estate. Lined with small one- and two-storey houses as Essex Street and renamed Romford Street in 1882, this was not a place that reflected well on the hospital and its closure was contemplated. In 1897 Rowland Plumbe, the hospital’s surveyor, produced a plan for the widening of Romford Street, intending to redevelop both sides all the way down to Commercial Road with terraced houses, standard save for the inclusion of top-floor workshops, an arrangement the propriety of which the hospital’s estate sub-committee questioned. In any case, the Ministry of Health thought the scheme left too little space at the backs and the LCC refused permission for the road widening. Plumbe made revisions and, exasperated by hold-ups, in January 1899 went to see Thomas Blashill, the London County Council’s Superintending Architect, with Arthur Crow, Whitechapel’s District Surveyor. LCC approval was immediately secured, provided the new houses did not exceed 24ft in height.

Davis Brothers (Israel and Hyman Davis) were lined up as the developers, but Plumbe now faced another unco-operative interlocutor in the person of Henry Legg, Mile End Old Town’s District Surveyor. After further delay, the southern part of the project was abandoned, land there having been compulsorily purchased by the School Board for London (Myrdle Street School opened in 1905). The northern part was recast to extend to Myrdle Street and in 1903 Israel Davis (Hyman had died in 1902) projected tenements, gaining the London Hospital’s approval for 80-year leases and for designs to be prepared by Rowland Plumbe & Harvey. Work began in late 1903. Disagreement as to whether the 24ft restriction applied to the eaves or overall height caused further difficulty – Plumbe prevailed with the former interpretation. By the end of 1905 the west side of Romford Street had been largely built-up. The eastern and western rows and a final pair of blocks (Nos 33 and 34) on Fieldgate Street west of Myrdle Street followed by 1907.

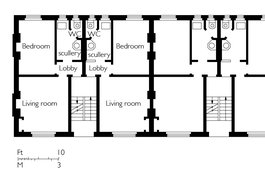

There were originally thirty-four blocks or sets of dwellings in all. Each had eight one-bedroom flats, so was deemed suitable for thirty-two people, all the flats having sculleries and WCs. Of red brick, variegated with stock-brick bands in the upper storeys, the elevations are broken and significantly enhanced by arched gablets over open staircases of fire-resistant (concrete) construction. The first occupants were largely Jewish immigrants.1

Leases were sold on, repairs were neglected by shady companies and their agents (slum landlords), a war-time bomb took out Blocks 20 to 22 at the south end of Romford Street, and by the 1950s overcrowding was recognised as a problem. In 1961 Edith Ramsay organised a conference to consider the growth of prostitution in the area. Better lighting was urged to deter casual sex in the playgrounds between and behind the mansions, yards that were regularly bridged by laundry. St Mary’s Ward, of which this area formed the western part, elected three Communist councillors in 1964 and 1968. From 1972 the mansions and nearby streets, particularly Myrdle Street and Parfett Street where many properties had been left deliberately empty, attracted squatters, including to all but the eastern row of Fieldgate Mansions. This occupation was inspired by the London Squatters Campaign, formed in 1968 to rehouse families from hostels or slums. With numerous local spin-offs this led to licensed squatting. Terry Fitzpatrick, in particular, worked with homeless Bengalis as the Bengali Family Housing Association to establish squatted tenure here and elsewhere in East London. The Bengali Housing Action Group ('bhag'_ _means tiger in Bengali) was formed in 1976.2

At the request of Tower Hamlets Council, the Greater London Council took action to outflank the squatters and to improve local living conditions. In 1979 David Levitt of Levitt Bernstein Associates (architects), Frances Bradshaw and Geoffrey Morris prepared a feasibility study for the rehabilitation and conversion of the remaining 256 flats in Fieldgate Mansions for the Samuel Lewis Housing Trust. The Parfett Street Housing Action Area was declared in 1983 through the GLC’s Area Improvement & Modernisation office. Enabled by the Housing Act of 1974, this attracted improvement grants and aimed to encourage existing residents to stay. The designation included all of Fieldgate Mansions. Plans for conversions involved knocking through to create some maisonettes to reduce crowding and to provide for some of the larger families in what was referred to in a GLC Press Release as ‘a close knit Bengali population’. Otherwise conservative in its treatment of the buildings, the overhaul involved the introduction of balconettes and the demolition of one block on the west side side of Romford Street for a tenants’ meeting room. The work was carried out to designs by Levitt Bernstein Associates. Fordham Bros Ltd of Dagenham were the builders in the first two phases of 1983–5, Thomas Bates & Son Ltd in the three later phases of 1986–91 that included the communal building and a playground.3

-

London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), GLC/AR/BR/22/BA/011831; District Surveyor's Returns: Royal London Hospital Archive, LH/A/9/41, pp. 85, 95, 200; LH/D/3/24, p. 70; LH/S/1/4: London County Council Minutes, 5 Oct 1897, p. 982; 6 Oct and 3 Nov 1903, pp. 1455, 1736; 4 Oct 1904, p. 1956; 30 Jan. 1906, p. 160: Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives (THLHLA), Building Control file 40670: Census returns: Isobel Watson, ‘Rebuilding London: Abraham Davis and his Brothers, 1881–1924’, London Journal, vol. 29/1, 2004, p. 68 ↩

-

THLHLA, L/THL/D/2/14/16; P/RAM/1/2/6; Building Control file 40663: interview with David Hoffman, August 2017 https://surveyoflondon.org/blog/2018 /david-hoffmans-photographs-and-recollections-squat/; Alex Vasudevan, The Autonomous City: a history of urban squatting, 2017, pp. 47–56 ↩

-

THLHLA, LC7797; Building Control files 40662–3: LMA, GLC/DG/PRB/35/040/222; GLC/DG/PRB/35/041/342 ↩

Builders and architect

Contributed by IsobelWatson on July 7, 2016

Fieldgate Mansions was nominally built by Davis Brothers, ie Israel and Hyman Davis; though Hyman died in 1902 part way through the course of the project. The building scheme was a large project by the London Hospital estate, and the builders seem to have been instrumental in securing the Hospital’s regular architect Rowland Plumbe’s part in taking forward the Mansions. 1

-

London Hospital estate records, LH/A/9/41, p 200 (July 1903). ↩

First development of the London Hospital estate west of New Road

Contributed by Survey of London on July 2, 2018

Until the middle of the eighteenth century, Whitechapel’s ‘field gate’ marked an edge of the built-up district at the west end of a footpath that led across fields to Stepney, a route the other end of which was to become Stepney Way. Once this path had been bisected by the New Road in 1754–6 its west end was less rural and ripe for development. Buildings followed in two phases, reflecting two landholdings. The western section, haphazardly built up from 1759 was initially called Baynes Street, after Edward Baynes, the landowner. But he sold up a decade later and it soon came to be known as Fieldgate Street through the older association. The eastern stretch was built up from 1787 as Charlotte Street, part of the London Hospital estate and named in honour of the Queen. In 1894 the whole road was unified and renumbered as Fieldgate Street.

Cooke’s Close, so called in the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, was a ten- or twelve-acre holding to the east of Baynes's land and south of Whitechapel Road properties on what by 1730 had become the Turner estate, from which it was separated by a ditch. It was held from the manor with the Red Lion Farm estate in the sixteenth century, descending from Sir Ralph Warren, mercer and Lord Mayor, to Anthony Holmead, merchant tailor, in 1598, and on to the Heath family.1 Cooke’s Close was mostly outside the parish of Whitechapel in Mile End Old Town, but its north part did cover what became Charlotte Street (the east end of Fieldgate Street) and the top ends of streets to the south that are now Settles, Parfett, Myrdle and Romford streets. The entire Cooke’s Close and Red Lion Farm landholding was sold to the Governors of the London Hospital by Henry Knight and Bailey Heath in 1755 and Thomas Heath in 1772.2

While Baynes and a successor, Anthony Forman, had taken action to develop their land, the part of the London Hospital estate immediately eastwards remained quiet until the 1780s. There was a four-acre tenter ground in its south-west corner, where now the southern parts of Settles, Parfett and Myrdle Streets run, present by the 1740s and occupied by John Cardell up to 1771. The builders of Greenfield Street were said to be infringing on hospital land in 1773 and in 1782 John Trapp, a local ropemaker, offered to spend £1,000 building on what was called Bun House Field, possibly a reference to Matthias Meacham’s tea gardens at the King's Head public house on the site of 32 Fieldgate Street. There was another ropewalk running east–west along the hospital estate’s northern edge.3

In April 1787 the hospital’s House Committee viewed ‘buildings now erecting in the vicinity of the Tenter Ground’ (presumably Greenfield Street) and decided to improve their rents by letting eight acres west of New Road on 61-year building leases. The hospital itself was safely distant and the completion of Greenfield Street seemed to demonstrate viability. John Robinson, the hospital’s surveyor, was directed to prepare an elevation and plan of ‘small streets’ in January 1788. Proposals for what were now lengthened to 99-year leases were invited and the first lots were let in July.4

Robinson had prepared a scheme for a rectilinear grid of narrow and mostly long streets, to be packed with terraces of two- and three-storey houses separated by small yards, scarcely gardens. Intended density was to be compounded by unintended interstitial development. Robinson’s approach was not repeated when development moved east nearer the hospital after 1810. Charlotte Street was laid down as a continuation of Fieldgate Street through to New Road, off of which Gloucester (Settles) Street and York (Myrdle) Street branched down to White Horse Street (Commercial Road). These roads were to be bisected by William (Fordham) Street. Building work progressed from the west and north, principally through Thomas Barnes, the prolific local bricklayer–builder,who had been active elsewhere on the hospital estate since at least 1773. Robinson attempted to impose close control and Barnes was reprimanded for using poor quality timber in June 1789.

Barnes took most of the north side of Charlotte Street in three parcels, the westernmost in December 1789 having already built a row of thirteen two-storey houses on an 118ft frontage (so only 9ft each). The next sections eastwards had been similarly built up by Barnes with around twenty somewhat larger houses by 1792. Barnes also laid out Charlotte Court to the rear, building fourteen houses on its south side in the 1790s and another twenty-some on the north side around 1810, all small, with one-room plans; living conditions here were later documented as particularly poor. West of the eastern entrance to the court was the Queen’s Head public house (see 83 Fieldgate Street), another nod to Charlotte. The easternmost 111ft of frontage pertained to Thomas Kincey, a New Road wheelwright–coachmaker.5

Land on the west side of Gloucester Street went to John Langley, another builder, in March 1790. He proceeded from north to south. The other lots proved harder to place. Charles Wilmot, a surveyor based close by on Union (Adler) Street where he had probably been involved in Holloway’s developments, took a large plot bounded by Gloucester Street (west), Charlotte Street (north), York Street (east) and William Street (south). He had begun building on more northerly frontages by March 1793, working with John Stocker, a Whitechapel carpenter. The early buildings that still stand on Parfett Street and the west side of Myrdle Street were all part of Wilmot’s development. Everything else further east and south, including the New Road frontage went in due course to Barnes.6

Wilmot, seemingly unrelated to the notorious Bethnal Green magistrate Davy Wilmot, was born in 1756, the son of Zaccheus Wilmot, a coffee-house keeper close to the Tower of London, who died in 1757. Charles Wilmot married Sarah Chapman in 1778 and was paying land tax for a property on Prescot Street in 1779. He was active on Greenfield Street as a surveyor from 1781. From 1784 he had a lease on two houses at the north end of Union Street on its east side. Sarah died in childbirth in 1786. Wilmot remarried in 1792 and was living on Greenfield Street by 1796 (at No. 82 in 1805) when he was advertising and selling bricks made in Southend, Essex. This suggests a source for the early stock bricks that can be seen in and around Parfett Street and Myrdle Street. By 1800 he was selling Southend property. Wilmot died in 1815 and was buried at St Mary Matfelon, Whitechapel.7

The war years from 1793 were difficult for builders, and, as in many other places, plans were compromised in terms of quality and space to make ends meet by packing more houses in. Robinson evidently did not resist these densifying changes which had no real effect on the hospital itself. Essex (Romford) Street appears to have been an afterthought of the mid 1790s by Barnes. Wilmot inserted Nottingham Place (Parfett Street) after 1803, running north off William Street as a cul de sac, initially not opening into Charlotte Street other than as a footway. Thomas Street and Roberts Place (either side of the south end of Parfett Street) were squeezed in by Barnes after 1800. The surviving houses of Nottingham Place (Parfett Street) and the west side of York (Myrdle) Street seem all to have been built after 1800. By 1807 Wilmot had built seventeen houses on the west side of York Street (of these 8–28 Myrdle Street survive) and Nottingham Place had been begun. All was complete by 1812, including the survivors at 15–21, 37–53, 22–26 and 34–60 Parfett Street, like those on Myrdle Street all in Mile End Old Town, not Whitechapel.8

By the end of the nineteenth century, Fieldgate Street and the streets to its south, especially Plumber’s Row, Greenfield Street and Nottingham Place, made up one of the areas in and around Whitechapel where Jewish immigrant settlement was densest. On Fieldgate Street alone there were at least five and possibly more small synagogues or _minyanim_in the period from the 1880s to the 1930s.9

-

Brtish Library, Add Ch 39408 ↩

-

Royal London Hospital Archive (RLHLH),RLHLH/S/10/1 ↩

-

John Rocque's map of London, 1746: RLHLH, House Committee Minutes (HCM), 21 May 1771, p. 298; 1 June 1773, p. 87; 27 Aug 1782, pp. 333–4 ↩

-

RLHLH, HCM, 17 April and 15 May 1787, pp. 279, 285; 8 Jan, 22 April and 1 July 1788, pp. 323, 342, 353 ↩

-

RLHLH, HCM, 9 June 1789, p. 60; RLHLH/F/10/3: Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archvies (THLHLA), P/BSA/1/5/1/1: London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), Tower Hamlets Commissioners of Sewers ratebooks (THCS): Richard Horwood's maps of London, 1799 and 1813 ↩

-

RLHLH, HCM, 2 Feb. and 16 March 1790, pp. 99, 106; RLHLH/F/10/3: THLHLA, P/BSA/1/5/2: THCS: Horwood] ↩

-

Ancestry: Old Bailey Online: LMA, O/009/056; CLC/B/192/F/001/MS11936/348/536366: General Evening Post, 21 Jan. 1792: Daily Advertiser, 7 July 1796: The Times, 1 Sept. 1800: The National Archives, PROB11/1569/141 ↩

-

RLHLH/F/10/3: LMA, Land Tax returns; THCS: Horwood ↩

-

Russell and Lewis,‘Jewish East London’, 1899: Census returns: Jewish Communities and Records - United Kingdom: information kindly supplied by Dr Sharman Kadish ↩

Romford Street from the north in March 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Fieldgate Mansions, typical ground-floor plan as built in 1905-7

Contributed by Helen Jones