St Paul's Church

church of 1846-7, founded as a sailors' chapel, converted to be a nursery in 2002

Dock Street's widening in 1845–6

Contributed by Survey of London on March 1, 2019

The widening of Dock Street in 1845–6 was a governmental ‘metropolitan improvement’ closely connected to the formation of Commercial Street. Linked by Leman Street, also widened at both ends, these road improvements were undertaken together by the Commissioners of Woods, Forests, Land Revenues, Works and Buildings to improve communications between the London Docks and the Eastern Counties Railway, incorporated in 1836 and with a terminus at Shoreditch from 1840. James Pennethorne was appointed in 1839 to be the Commissioners’ architect and surveyor responsible for these and other new streets, working jointly with Thomas Chawner, who retired in 1845.

Following a suggestion put to a select committee in 1836 by Lt.-Col. John Castle Gant, chairman of the Tower Hamlets Commissioners of Sewers, a plan for a road initially intended to relieve congestion around Aldgate was extended to link the docks to the as yet unbuilt railway via Leman Street. Two years later a deputation from Whitechapel parish presented details for the line, explaining that twenty-five houses would need to be cleared from the east side of Dock Street, then only 15–17ft wide. Acts of Parliament in 1839 to 1841 (2&3 Vic. c.80, 3&4 Vic. c.87 and 4 Vic. c.12) provided funds derived from duties on coal and wine for the formation of the new 55ft-wide thoroughfare from the London Docks as far north as Christ Church Spitalfields. The net cost of the Dock Street section was assessed as £35,783 15 8.1

A want of ready money postponed property purchases to 1842–4, Clearance, including of soap and soda-water factories in what had been sugarhouses, and pavement formation followed in 1845–6, vaults being formed to Pennethorne’s plans by John and Charles I’Anson, Fitzroy Square builders. The new frontage plots were auctioned off, but St Paul’s Church and its parsonage excepted they were slow to be taken. The north corner was built up in 1853–4, otherwise nothing happened until the 1860s by when freeholds were sold as an added inducement.2

A drinking fountain in the middle of the Dock Street–Leman Street junction was perhaps part of the 1840s improvements. Dilapidated, it was replaced in granite in 1879 in memory of Sir Francis Goldsmid MP, then removed in the 1930s.3

-

London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), THCS/057: Report from the Select Committee on Metropolis Improvements, 1836, pp. 43–4: Second Report from Select Committee on Metropolis Improvements, 1838, pp. viii, 95–8: First Report from Select Committee on Metropolis Improvement, 1840, pp. 7,9,17–24,53: The National Archives (TNA), WORK, 6/99, pp. 6,19: _Oxford Dictionary of National Biography _for Pennethorne ↩

-

TNA, CRES60/5–6; WORK6/93–4: LMA, SC/PM/ST/01/002: Illustrated London News, 4 Oct 1845, p .215 ↩

-

The Builder, 12 Oct. 1878, p. 1071: Morning Post, 19 June 1879, p. 5: Ordnance Survey maps ↩

St Paul's Dock Street

Contributed by Survey of London on March 1, 2019

Once the Sailors’ Home on Well Street had opened in 1835, Capt. Robert Elliot was on the lookout for an opportunity to establish a ‘Sailors’ Church’ nearby, to supersede the Episcopal Floating Church, now both decaying and inappropriately located. With the widening of Dock Street in train in 1842, the Home sent a deputation to the Earl of Lincoln, Chief Commissioner of Woods and Forests, eyeing a site behind the Home on what would become the new street’s east side. Thomas Webster was willing to sell other necessary land, but distractions followed. In 1843 Henry Roberts, acting as the Home’s architect, recommended acquiring the sugarhouse at the south end of the east side of Well Street with premises back to Wellclose Square, seeing that as a better site for the church. Then negotiations towards acquisition of the former Danish Church in Wellclose Square opened, but these ideas were abandoned in 1844. Elliot, collaborating with Lord Henry Cholmondeley and Capt. Henry Hope RN, returned the focus to the east side of Dock Street in early 1845 and terms were agreed with James Pennethorne, the Commissioners’ architect and surveyor, for the acquisition of a 70ft frontage for a sailors’ church. The land would be sold for £1,200, less than its market value, in recognition of the charitable intentions. There was provision for a passage north of the church to give direct access to the Home, and for a chaplain’s house beyond. A desire to identify the Sailors’ Home as the parent of the church on its façade came to nothing.1

A public meeting at Crosby Hall was convened on 30 April 1845 to put the erstwhile floating church on a ‘more permanent footing’. Chaired by Thomas Hamilton, ninth Earl of Haddington, First Lord of the Admiralty, alongside Charles James Blomfield, Bishop of London, an indefatigable church builder, especially in East London, it was well-attended. It opened a subscription fund to pay for the intended church and formed a committee, largely made up of men involved with the Home. Elliot was the chairman, closely deputised by the project’s treasurer, John Peter Labouchere, a prominent banker and another evangelical (also the brother of the politician Henry Labouchere, Baron Taunton), who had been one of the Home’s original trustees and its treasurer since 1834. Among others actively involved were Cholmondeley, Hope, Capt. Francis Maude RN, Capt. William Waldegrave RN, Capt. W. E. Farrer, S. B. Brooke, Andrew Johnson and the Rev. Charles Adam John Smith, chaplain of the floating chapel.

Half of a £6,000 target, to cover the land, building and an endowment, had been promised within two months. Henry Roberts presented first plans for the church in July 1845, aiming to seat 600 on the ground floor and 300 more in side galleries. There was some to and fro as to whether the galleries were needed. Stone facing was initially thought an extra and there were disagreements as to the relative priorities of galleries as against stone facing. In the end both were included and there were 800 free seatings. Roberts’s ‘Early English’ style was approved in October, but he was asked to make the tower loftier and to cap building costs at £4,100. By January 1846, when subscriptions had reached £5,918 and the estimated building cost £4,500, Roberts had gained agreement that the tower should be placed to the north to allow for a lobby porch to the south. Pennethorne and Blomfield both asked for a façade of stone or ‘Patent Portland Cement’. In March, with the new road approaching completion, the building contract went to William Cubitt & Co. for £5,826, the lowest tender. The façade would be ragstone and the spire would be postponed if funds ran out. Work began with John Birch as the Clerk of Works. On 11 May 1846 Prince Albert laid a foundation stone in the company of Blomfield, numerous admirals and other eminent figures, with a choir of seamen and their apprentices. By June the total sum needed had risen to £9,000, of which £2,000 had still to be raised. Even so, completion of the steeple was agreed and the whole work was completed in early 1847. Costs had risen to £7,013 and £9,020 had been raised, no single contribution being greater than £105. The Prince Consort returned for Blomfield’s consecration of St Paul’s Dock Street Church for Seamen of the Port of London on 10 July 1847. The Rev. Charles Besley Gribble was appointed the first Minister.2

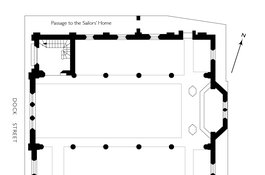

Predictably,_The Ecclesiologist _pronounced in 1846 that ‘The design is extremely poor: a vulgar attempt at First-Pointed…. There is not the least idea in the composition…. The whole is stale and insipid.’3 By Puginian standards perhaps, but Roberts’s church has solemn and proportional solidity in keeping with its evangelical origins, and it survives to impart a touch of dash to an otherwise largely disappointing streetscape. The three-stage tower rises to a broached Portland stone octagonal spire with lucarnes. This reaches 100ft to make a landmark that was originally topped by a copper weather vane in the shape of a model ship, a flourish _The Ecclesiologist _thought ‘singularly vulgar’. The gable-fronted nave sports a large triple lancet with banded shafts below a sexfoil circle window. X-pattern iron pavement railings were removed during the Second World War. There are clerestoreys on the five- bay brick-faced returns and half dormers on the north aisle to ensure good light once the street was built up. An open timber roof with braced queen-post trusses rests on octagonal piers of ‘Carline-nose’ (Scottish) stone, said to resemble Purbeck marble, but long ago painted. Carved heads articulate the hood moulds above the piers. There were oak benches for 600 on the ground floor and side galleries for 200 more, with no west gallery. The pulpit and reading desk, both hexagonal, stood in front of a shallow almost vestigial hexagonal chancel; there was a small vestry to the south. The original stained-glass two-light east window, presented by Prince Albert and made by William Wailes in Newcastle, bore a passage from the 107thPsalm, ‘They that go down to the sea in ships …’. The organ was made by Gray and Davison in 1848.4 Among numerous wall-tablet memorials, many recording pathetic seaborne misfortunes, primacy in date and significance belongs to a Gothic tabernacle south of the chancel arch commemorating Elliot, who died in 1849, this made by R. Brown of Bloomsbury.

In 1863–4 the Rev. Dan Greatorex (1828–1901) began a long and energetic ministry by getting the sailors’ church assigned a parochial district to fight off the spread of ritualism from St George in the East. At the same time, Edward Ledger Bracebridge, the architect then overseeing enlargement of the Sailors’ Home, assessed the steeple as unsafe. Its rebuilding ensued in works by Frederick and Francis John Wood of Mile End that included moving the organ to the west end of the south gallery, and replacing the altar reredos in stone.

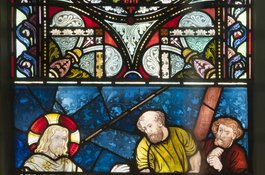

Stained-glass windows began to accumulate. On the north side there are two early nautical scenes, trefoiled top and bottom, one showing a lighthouse, the other commemorating Rear-Admiral Sir William Edward Parry, the Arctic explorer, who had been involved with the church from the first up to his death in 1855. It depicts his ship, the Hecla, forced against an iceberg in 1825. Greatorex put up the three-light west window in 1872 in memory of Capt. Sir John Franklin, another Arctic explorer who had attended the Crosby Hall meeting to set up the church shortly before departing on his final disastrous expedition. This was made by Cox & Sons of London and shown in part at the International Exhibition at South Kensington. It illustrates incidents from Christ’s life relating to the sea. An additional east window was dedicated to Capt. John Thomson who died in the wreck of the _Gossamer_in 1868. More prosaically, churchwardens John Butler, a Wellclose Square haberdasher, and William Henry Graveley, a City surveyor, had windows placed, respectively, to the south in 1872 and the east in 1875. Another north-aisle window of 1902 was made by Jones & Willis.5

Greatorex retired on account of ‘overwork and paralysis’ in 1897. His successor, the Rev. Edward G. Parry, had a flat-roofed choir vestry built between the south porch and the clergy vestry in 1899, and then reordered the interior in 1901. Thomas John Fox was his architect, G. E. Weston the builder. They took down the long disused galleries, introduced a central aisle and formed a raised chancel with choir stalls and iron rails. Seating thus reduced to 473 was thought ‘amply sufficient’. Decorative painting of the east wall with Gothic arches enhanced the reredos. The organ, rebuilt by Hele & Co., moved to the southeast corner and St Mark’s chapel was formed in the northeast corner. All this cost £1,600.6

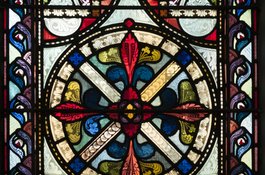

The Rev. Joseph Williamson arrived in 1952 and instigated further ritualist alterations achieved gradually up to 1959. A. G. Nisbet of J. Douglass Mathews & Partners was his architect, with R. W. Bowman Ltd the builders. First they enlarged the sanctuary and further reduced seating, removing the clergy and choir stalls and three rows of pews. An aumbry was installed in the south wall and the model-ship weathervane was taken down, repaired and rehung. In 1956 Williamson put in a new east window in memory of Vice-Admiral Rev. Alexander Riall Wadham Woods, Chaplain to the Red Ensign Club from 1933 to his death in 1954, as well as to those of the parish who had lost their lives in the recent war. Depicting SS Paul and Nicholas, it was unveiled by the Queen Mother. Another single-light window portraying St Mark went up in the chapel of his name. Finally, a window of Mary with the infant Jesus, made to designs by Colwyn Morris, was inserted on the south side in memory of Mary Emma Mason. Morris probably also designed the other windows of the 1950s, all likely made by James Powell & Sons (Whitefriars Glass).7

Use of the church declined in a neighbourhood dominated by slum clearances in which Catholicism was in any case the dominant religion. Following dock closures, in 1971 the parish merged with that of St George-in-the-East. Further decline partly associated with a new Muslim demography led to a declaration of redundancy in 1983 when the St Paul’s Trust Centre gained permission for a change of use to community, recreational and educational purposes. But this did not materialize and after closure for worship in 1990, around when the ship weathervane was moved to St Paul’s School, reuse continued to prove difficult to establish. A long lease was advertised in 1994 and a restaurant conversion approved in 1998, but it was 2000 before a viable scheme could be acted upon. Irene Beaumont (Selective Estates) then established a private nursery that opened in 2002. Alterations included the removal of the remaining pews and the insertion of floors in the aisles and at the west end behind steel-framed glazed partitions that are designedly reversible. Dave Hubble was the architectural consultant, working with D. Suttle and Associates, engineers.8

-

National Maritime Museum (NMM), SAH/1/1, pp. 148,240,249–51,279,328; SAH/1/2, pp. 8–9,23–5,32–8,175: The National Archives (TNA), WORK6/94, pp. 320–1 ↩

-

London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), P93/PAU2/019: NMM, SAH/3/1: TNA, CRES60/6: www.rbs.com/heritage/people/john-peter- labouchere: The Builder, 21 March and 3 May 1846, pp. 142,221: Illustrated London News (ILN), 16 May 1846, p. 321 ↩

-

The Ecclesiologist, vol. 6, 1846, pp. 34–5 ↩

-

LMA, P93/PAU2/019: DL/A/C/MS19224/550: ILN, 16 May 1846, p. 321 ↩

-

LMA, P93/PAU2/020, /030, /034, /055–6, /089–098: Building News, 28 March 1873, p. 381: information kindly supplied by Peter Cormack and Michael Kerney ↩

-

LMA, P93/PAU2/020, /022, /211, /258; DL/A/C/02/047/029; DL/A/C/02/081/078; District Surveyors Returns ↩

-

LMA, P93/PAU2/084–8, /101, /215–19; DL/A/K/01/16/097; DL/A/C/02/100/120; DL/A/C/02/101/114; DL/A/K/01/16/099; DL/A/C/02/104/087: Church Times, 27 Feb. 1953: information kindly supplied by Peter Cormack and Michael Kerney ↩

-

Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives, Building Control files 21371, 26550: Hackney Gazette, 7 July 1972: East London Advertiser, 3 June 1983; 26 Nov. 1998, p. 4: The Standard, 14 Sept. 1983: Tower Hamlets planning applications online ↩

St Paul, Dock Street, chancel, August 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul, Dock Street, east window, August 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul, Dock Street, detail of reredos, August 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul, Dock Street, Parry memorial window, north wall, August 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul, Dock Street, c. 1905

Contributed by Aileen Reid

St Paul, Dock Street, Elliott monument, east wall, August 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul, Dock Street, detail from west window, August 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul, Dock Street, west window inscription, August 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Church of St Paul from the north-west in 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul, Dock Street, plan as in 1847

Contributed by Helen Jones

St Paul, Dock Street, detail of west window, August 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul, Dock Street, detail of west window, August 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul, Dock Street, detail from west window including Franklin inscription, August 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul's Church, Dock Street, 1980

Contributed by danny