Peabody estate A Block

Contributed by danny on June 4, 2017

I have lived in this block since 1970. My mum and dad moved into this block when it was modernised. Before that, we lived in one of the other blocks on the estate - C block, further down (south) on the street. When we moved into A Block it was the first time ever that we had a proper bathroom and separate toilet as well as running water (hot and cold) inside.

Before then, we shared two communal toilets along the landing in C Block with four other flats and we got our water, cold only, from a tap at two communal sinks adjacent to the toilets.

Before the modernisation was completed, I remember climbing with other kids up the scaffolding surrounding the block as work was underway and peering in the windows hoping that we might get a chance to live in one of these new flats.

At the time, my dad worked for London Transport on the underground at Monument Station and I think my mum worked in a clothing factory at that time as a tea lady. Both had come from Co. Donegal in Ireland in the late fifties. I was born like my two sisters in the London Hospital in Whitechapel Road.

1970 was a big year, it was the year I transferred to secondary school - I had until then attended my local primary. Tower Hill Catholic School which had originally been in Chamber Street and which had transferred to a new building in St Mark Street when it became English Martyrs JM&I Primary School in 1969. In 1970, I started at the London Oratory School in West Brompton, Fulham which was also a brand new building.

During the summer of 1970, me and my sisters had all learnt to swim at the new St George's Swimming Pool on the Highway just past Cannon Street Road.

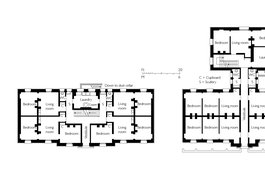

A Block was, in its modernised condition, home to 20 flats. Four on each of its 5 floors (ground to fourth floor). Our neighbours were a mix of English, Irish, Maltese, but at that time few Bangladeshi or Black people. Over the years, the block had many comings and goings of people and in more recent times our neighbours have included people of Irish descent like us, Poles, Ethiopean, Sudan, Portuguese, Scottish, St Lucian, Bangladeshi, Brazil, and even some English people who were always a rarity!!

Eventually, my dad and then in more recent times, my mum died and I got married to a girl of Irish descent too. We were given a flat and have raised three daughters here. We brought our girls up in a two bedroomed flat. I found the only place I could get treble bunkbeds was in France and I bought some and travelled to France to pick them up in our car in the mid 1990s. The girls have grown up very close to each other and we remain a typical closeknit London Irish family. All the girls went to the same primary school I did, and to the same Catholic secondary girls school in Hackney that my sisters went to. They all got places at UCL in London, one of the world's top universities and have graduated with 2.1 degrees.

As a family, we were fortunate to have had Irish parents who came from that generation who although not having benefitted to a great extent from education themselves, because of poverty and the need to contribute to family incomes by going to work at fourteen, they did recognise the joys and importance of learning. We always had books in the house, and our parents always took us out on trips when they could afford to do so by train or bus and neighbours kids too if possible. We did quite well at school and we passed on this joy of learning and knowledge to our own kids. I strongly disagree that poverty is a barrier to learning and success. Cultural influences and support from a strong family can overcome these potential obstacles.

In recent years, the block has remained a great community to live in with a good set of close neighbours who have always kept an eye out for each other. I was fortunate to work in a public sector role for many years and then in the business consulting arena with lots of opportunities to work with big companies overseas. I even spent a short time working in the Middle East. These chances to travel and to facilitate the rest of the family to do so, stood in often stark contrast to many of our neighbours. Poverty, joblessness, low-paid jobs and mental health issues took their toll on many of our neighbours. It is clear to me, that having access to a little extra money, doing jobs that are not hard manual labour nor involving long, anti-social hours with little reward, have a major impact on one's health. My own father worked many night shifts in his job for London Transport and did not live more than three years beyond his retirement. I hope I will not befall the same fate. I'm assured that at least having worked for forty years, I have some reasonable additional pension available above and beyond the state one to see me through.

The local area has seen many changes over the years - an increasing Bangladeshi population although that group may well be following others on that journey to the suburbs and home ownership. We never had the concept of Right to Buy in these Peabody flats and I'm politically opposed to it and what it has done to affordability of homes for most people in Britain. Certainly, my own kids see no way they can afford to live in the area they grew up in, nor in London because of prices. Drugs dealing has become a major problem in recent years. A local charity once had a hostel in a former seaman's home locally, and their residents brought major dealing and purchasing to local streets. That problem persists today even though the hostel is now a BackPack hostel for travellers. Many tenants seem to have serious mental health or dependency issues and these also cause disruptive behaviour in the area. A gang culture amongst local youths also leads to problems and occasional clashes. Much of this gang culture is also related to drug dealing and lack of opportunity as well as some degree of alienation from their parents' generation because of language and traditional cultural expectations about jobs, relationships and religion.

The area has at the same time become more gentrified. In the late 1970s - the area was actually dying - the docks has closed, this was still a place littered with post-war 'bomb sites' and derelict warehouses that we kids took great pleasure in playing in. But with the incessant increase in house (or should I say apartment) prices, new builds have been going up all round the area bringing many new Europeans and other world citizens who frequently work in financial services, the law or other business in the City. This has led to us seeing a local Safeway store in St Katharine's become firstly a Morrisons and then (best of all) a Waitrose. These are generally positive developments but the area has become even more divided between haves and have-nots.

Our block is well over 140 years old. It features in an illustration from the Jack London book People of the Abyss and records of the Old Bailey even recount a vicious murder in the block in the late 1800s. But it still provides decent homes as George Peabody, the founder of the Peabody trust sought to do, and long may it do so.