Angel Alley

Contributed by Survey of London on Sept. 12, 2019

Angel Alley, named after the Angel Inn at 85 Whitechapel High Street and

reached via a simple doorway through No. 84, exists now only as an access

passage to the Freedom Press and its bookshop (No. 84B). Its east side is

formed by the Whitechapel Gallery’s extension of 1984–5, and the alley has

terminated since 1899 beyond the Press in a slight dogleg that once led to a

straight narrow path north to Wentworth Street.

In the seventeenth century the southern half of the alley’s east side formed

part of John Enion and Samuel Cranmer’s large holding that ran through to what

became Osborn Street. This included a large house, probably that occupied on

and off by Richard Loton and his son and grandson, Edward and Samuel, from the

1650s to the 1690s, and in the 1670s by John Wells, the brewer and business

partner of Abraham Anselme, tenants of Loton’s Swan brewery in the 1660s and

1670s.

Angel Alley’s late seventeenth-century occupancy was varied. Residents in the

1670s included Samuel Pepys’s lover Deb Willet and her husband Jeremiah

Wells. In the 1680s and ’90s the mathematician Euclid Speidell lived here,

his first name indicating that his father, who published on logarithms, as did

Euclid, was also a mathematician. While he taught ‘next door to the cock in

Bow Street’, in Angel Alley he published and sold his books.

Until the early eighteenth-century advent of sugar refining, many Angel Alley

residents were involved in the cloth trades. By the 1670s there were short

rows of small houses on the east side by the High Street, and further north on

both sides, probably mainly occupied by lowly clothworkers. Some were not so

lowly. Peter Stone, a silk thrower who died in 1686, lived in a nine-hearth

house here in the 1660s and ’70s, probably the largest house on the west

side. Further south on the west side, by 1693 until his death in 1729,

was John Cordwell, a citizen framework-knitter. He was implicated in another

feature of Angel Alley, the practice of independent-minded religion. In 1719

Cordwell raised a subscription for a publication by Richard Welton, the high-

church Tory Jacobite former Whitechapel rector who had been deprived of his

living in 1715 for refusing to swear allegiance to George I. Government agents

raided Welton’s chapel in Goodman’s Fields in 1717 and he and forty others

were arrested. It was at Cordwell’s Angel Alley house that Welton was again

apprehended in 1724; he soon departed for Philadelphia.

Most nonconformity in Angel Alley and wider Whitechapel was of a quite

different stripe. In 1672, under the Royal Proclamation of Indulgence allowing

the licensing of Nonconformist worship, Richard Loton’s houses in Spitalfields

and Angel Alley were licensed for worship led by John Langston and William

Hooke, Congregationalist ministers; the Angel Alley licence was never taken

up. Loton was a clothworker turned brewer who had been an energetic

Parliamentarian and Independent in the 1640s.

Around 1714 a congregation of Particular Baptists, who had previously met in

Tallow Chandler’s Hall in the City and in Alie Street, built a small meeting

house on the west side of Angel Alley under the pastor John Nichols who was

succeeded from 1715 to 1729 by Edward Ridgeway. Tax on this meeting house was

paid in 1743–5 by Samuel Stockell, ‘Sam the potter’, who was a ‘High

Calvinist’ from the Petticoat Lane area, and minister of the Independent

meeting in Redcross Street, Southwark, from 1728 till his death in 1750. The

site in Angel Alley was still referred to as ‘ground belonging to the Meeting’

in 1766.

The decline of the meeting house coincided with the rise in Angel Alley of

sugar refining. Samuel Lane, a sugar refiner and distiller, had premises on

the east side by 1719, on part of what had been Cranmer and Loton’s holding,

that included a timber-framed house, possibly Loton’s. After Lane’s death in

1741 the sugar house was enlarged and improved by his son Joseph who died in

1753. By 1732 Cordwell’s house on the west side had been taken over by John

Bromwell, another refiner who also had a sugar house in Leman Street. Bromwell

rebuilt the Angel Alley sugar house on a modest scale and after his departure

in 1741 it passed to John Arney. Burnt down in 1749, a common occurrence in

the industry, it was rebuilt by John Titien, in partnership until his death in

1757 with John Christian Suhring, who by the time of his death in 1777 had

extended the sugar house to occupy the whole site between Angel Alley and

George Yard.

A measure of increasing affluence in Angel Alley once sugar refiners

established themselves is the description in 1765 of the household goods of

the refiner Nicholas Beckman who had taken over Lane’s premises on the east

side, with a ‘great Variety of rich Household Furniture … a very elegant

wrought Epargne … large services … most beautifully painted in Landscapes and

Figure … cut glass lustres with twelve arms to each’. After Beckman left,

his premises were taken over by Frederick Rider, a refiner who went bankrupt

in 1773 also in possession of a substantial estate at Woodford. Rider’s

property, including the sugar house, had at £1,350 one of the highest

insurance values in Whitechapel in 1767. It included a two-storey house, 34ft

by 19ft, four rooms of which were fully panelled, three with marble

mantelpieces. There was also a three-storey timber building for servants’

rooms, possibly Loton’s former house, plus a large coach house and stable. The

roomy brick house and new sugar houses were enlarged again by William Pycroft

and Samuel Payne, Pycroft later operating with William Wilson. By the late

eighteenth century, Angel Alley’s sugar houses tended to form parts of larger

businesses with premises elsewhere. Associated facilities appeared, such as

the sugar cooperage of two brothers, Jonas Gandon (1756–93) and Peter Gandon

(1761–1814), whose father Jonas (1726–?) had a leather business in Hooper

Square in the 1760s. The brothers began in a small way on the alley’s west

side near the corner with Wentworth Street in 1790, and by the time of Peter’s

bankruptcy in 1805, the site included a house on Wentworth Street, a three-

storey workshop and warehouse, 175ft long and 40ft wide, with a long narrow

yard on its east side fronting the west side of Angel Alley. Gandon decamped

to Osborn Place, Brick Lane, to more general coopering, continued there by his

descendants till the 1840s.

Suhring’s west-side sugar house survived as a refinery under a succession of

owners – his nephew John Gask let it in 1777 to Jeremiah Glover, who expanded

the premises, which grew again from 1783 under Richard Samler (d. 1816) and

Thomas Ferrers, Samler being part of a family with extensive sugar houses in

the City and elsewhere in Whitechapel.

Pycroft’s east-side sugar house was sold in 1806 when the premises extended

east to Osborn Street. It was last used as a sugar house about 1826 by Walton,

Fairbank & Co. who also had premises in Lambeth Street. By 1852 it

had been taken over by Ind Coope, whose former Coope sugar refinery on Osborn

Street adjoined its north side. A beer-barrel warehouse, which survives, was

built on the Angel Alley side of the site. Sugar refining was moving further

east and south, where there was room for expansion. Other businesses took over

the buildings in Angel Alley.

John Kelland’s City Saw Mills, first established on Wenlock Basin, City Road,

in the 1820s, and on Wentworth Street by 1834, expanded to take over a long

narrow site that snaked down the west side of Angel Alley, previously that of

the Gandons’ cooperage. By 1843 Kelland had premises that consisted of

buildings several storeys high including mills, machinery rooms, stables and

an engine house at the south-west corner, the source of a devastating fire

that year. The site was cleared in 1882.

Angel Alley suffered decline in the nineteenth century, like most of the

streets and courts north of the High Street. Many houses fell to use as ‘low’

lodging houses, charging 3 d. a night. On his visit to ‘the Back of

Whitechapel’ in 1861, John Hollingshead deplored the impression he gained that

the ‘best paid occupation appears to be prostitution and it is a melancholy

fact that a nest of bad houses in Angel-alley, supported chiefly by the

farmers’ men who bring hay to Whitechapel market twice a week, are the

cleanest-looking dwellings in the district. The windows have tolerably neat

green blinds, the doors have brass plates, and inside the houses there is

comparative comfort, if not plenty.’ The East London Association

‘established for the suppression of vice, etc’ pursued prosecutions of

brothel-keepers and succeeded in closing twelve establishments in Angel Alley

and Wentworth Street by the end of 1862. In an effort at mitigation, a lease

of four houses at the north-east end was acquired in 1875 at the Rev. Samuel

Barnett’s suggestion by Edward Bond and the Earl of Pembroke, for improvement

and letting to respectable tenants. One was occupied in the 1880s by the

Salvation Army ‘slum sisters’, later at 78 Wentworth Street, but the houses

were demolished around 1892 when Gustav Wildermuth’s lodging house was built

in Wentworth Street.

Further south in Angel Alley the George Yard Mission had expanded into a

building on the west side by 1876. In 1886 the Mission erected two new

buildings opposite replacing old houses: Shaftesbury House, used as a library,

office, kitchen and caretaker’s rooms, and a new infants’ school. Opened by

the Duchess of Teck, these were the work of the architect John Hudson, the

infants’ school having some architectural presence, its windows elaborated

with pediments. Its basement was used originally for boys’ industrial classes,

the ground floor as day and infant schools and in the evenings for clubs and

benefit societies, the first floor for what would now be called youth work

with young men and women, including ‘ambulance classes’, as well as Bible

classes. The second floor had three rooms for a crèche and nursery, open in

its early days from 7.30am to 8pm. The flat roof was intended for use as ‘a

prettily arranged encampment for babies’ in the summer’.

Angel Alley was reduced to the rump that it is today in 1899 when the

Whitechapel District Board of Works expanded its George Yard depot across its

northern part. The George Yard Mission buildings were sold off in 1923:

Shaftesbury House became 84C Whitechapel High Street and was in use as a

tailor’s before it was badly damaged during the Second World War and

demolished around 1947. The infants’ school survived until about 1982 when it

was demolished to make way for the extension of the Whitechapel Gallery.

The Freedom Press and Bookshop, 84B Whitechapel High Street

Contributed by Survey of London on Sept. 12, 2019

Despite its address, this curious survival of both evangelical and radical

Whitechapel is located in Angel Alley. It is a four-storey stock-brick

building, exposed on three sides, narrowing towards the north end which is

canted to follow the curve in the alley’s direction. The site was historically

part of the Angel Inn at 85 Whitechapel High Street and was used as a yard

from which Thomas Gardner ran his hay and straw business from 1825 to 1865.

The building was new in 1869 when its lease was offered for sale to ‘Owners of

Small House Property’, described as ‘a newly erected tenement, containing 10

rooms with yard and washhouse, in Angel-alley, at the back of the “Angel” wine

vaults’. After use as a general lodging house, by the end of 1876 it was

occupied by the George Yard Mission, connecting to the ragged school across

the back of 86 Whitechapel High Street. It was adapted as a shelter for the

schoolchildren, and in 1901 housed five boys and girls aged from four to

fourteen, a matron, and two domestic servants. The building had ceased to be a

shelter byabout 1910, and was sold with the Mission’s other Angel Alley

properties in 1923. At least partly residential in the 1920s, 84B Whitechapel

High Street, as it had become, was used through the 1930s by Morris Mindel and

Abraham Sorotkin, bookbinders, singly or in partnership.

No. 84A, opposite, the Mission’s former infants’ school, was then occupied by

Express Printers, a firm specialising in printing in Hebrew and Yiddish that

expanded into No. 84B during the Second World War. On the death of the printer

in 1944, the business was acquired at a bargain price by Vernon Richards

(1915–2001), an anarchist activist who was able to recoup some of his costs by

selling the Hebrew type.

Richards had been born Vero Recchioni, the son of an Italian anarchist who

owned a café in Soho. Since 1936 Richards had been a contributor to the

anarchist newspaper Freedom. This traced its origins to 1886 when Henry

Seymour and Charlotte Wilson, a former Fabian, invited Peter Kropotkin to

England. That October Wilson and Kropotkin began publishing Freedom: A

Journal of Anarchic Socialism (soon changed to Anarchistic Communism) as a

monthly newspaper from William Morris’s Socialist League offices. From 1889

the Freedom Press also published books by a wide range of socialists,

positivists, communists and anarchists, from Morris and Kropotkin to Herbert

Spencer and Emma Goldman. The organisation prospered, in 1897 taking over

Commonweal, Morris’s former journal, and the printing presses of William

Michael Rossetti’s three children, who had founded a short-lived anarchist

journal, The Torch, at 127 Ossulston Street in Somers Town, where the

Freedom group remained until 1927.

Vernon Richards began contributing to Freedom during a period of flux when

the journal and press had no fixed home. This changed in 1944 when he acquired

Express Printers, which began printing Freedom, although editorial work

continued elsewhere until 1945, often in the homes of the group’s editors and

contributors. The Freedom group had been under investigation since the

beginning of the war. Soon after the acquisition of Express Printers, with the

war still on, Richards, his wife and fellow activist, Marie Louise Berneri, Dr

John Hewetson, Freedom’s publisher, and Philip Sansom, another contributor,

were charged and the three men sentenced to nine months in prison for

publishing encouragement to insurrection among the armed forces in War

Commentary, published by the Freedom Press. The formation during the

trial of a Freedom Press Defence Committee which included influential

establishment progressives and free-speech advocates from Herbert Read and

George Orwell to Bertrand Russell, Harold Laski and Vera Brittain, helped

ensure relatively lenient sentences. Printing continued in the ‘decrepit brick

dungeon’ in Angel Alley and more stability came with offices at 27 Red Lion

Street, Holborn, from 1945 to 1960, through which period Colin Ward, the

housing and planning historian, was an editor. Freedom Press had first opened

a bookshop in Red Lion Passage, off Red Lion Street, in 1940, only for it to

be bombed out in 1941.

Anarchism is notoriously factional and the 1960s saw Freedom supplemented by

enterprises such as Black Flag and, from 1983, Class War, suspicious of the

intellectual, bourgeois, libertarian streak represented by Read, now a regular

contributor to Freedom. For more than sixty years Freedom Press’s financial

viability was ensured largely through the efforts of Richards, who had a knack

for extracting funding from ‘anarchists made good’ (and even from ‘anarchist

picnics’ in the United States, often attended by sympathetic Italian

Americans).

The single most propitious act for the group’s survival was Richards’s

acquisition in 1968 of the freeholds of both Nos 84A and 84B; on the death of

the previous owner, the son offered these at an attractive price. Printing and

editorial functions were united in Angel Alley. There was theft and damage to

printing equipment (supposedly by ‘Hell’s Angels’) when the buildings were

squatted by students, unconcerned about security – ‘packed bodies, lit by

lamps and candles, slept on mattresses’. Freedom moved out of No. 84A in

1969 and into No. 84Bhaving strengthened its ground floor to take the printing

presses. No. 84A, the old school, became offices for a shipping agent and by

1975 had been sold to the Whitechapel Gallery, which converted the building

into a lecture hall and bookshop, landscaping the site of Shaftesbury House

(No. 84C), before demolition in 1982 for the gallery extension on the site of

Nos 84A and 84C.

Presses occupied the ground floor at No. 84B until the Aldgate Press, founded

in 1981, took over the printing of Freedom. From around1997 till it moved to

Bow in 2015, this was from a unit in Sherrington Mews in Gunthorpe Street. In

1982 Richards transferred the ownership of No. 84Bto a trust (‘so it could

survive in the event the Collective didn’t’), the Friends of Freedom Press

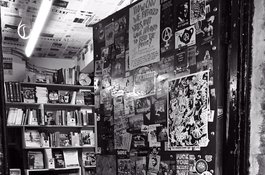

Ltd. From around then, the ground floor was an almost impenetrable labyrinth

of stocks of books and copies of Freedom. The bookshop was in one of two

first-floor rooms until about 2005, the other was used for typesetting then,

once printing was done off-site as a ‘hacklab’. The second floor was

originally an archive of papers, books and pamphlets, later an editorial

office. The top floor was a store and an office for ‘A’ Distribution, set up

in Islington in 1980. Since the 1980s the newspaper’s readership has

dwindled and in 2014 it ceased to be a monthly paper, moving online as a

newsletter, with occasional paper publication. In its place the bookshop,

occupying the ground floor since soon after 2000, and publishing have

increased in importance and scope. The ‘clapped-out four-storey pile

preserved, in the main, as a corner of east London eccentricity’has also

provided office space for other protest and radical groups, including the

National Union of Mineworkers (during the 1984 miners’ strike), the Anarchist

Federation (founded in 1986), the Advisory Service for Squatters, Corporate

Watch, Haven, the London Coalition Against Poverty and Solidarity Federation,

and as a place for other anarchist groups to meet and give talks. In 1996

black-and-white illustrative panels were installed in the alley’s entryway. A

further rectangular steel panel was added within, on the back part of 85

Whitechapel High Street, near the door to the Freedom Bookshop, with black-

and-white portraits of thirty-six radicals, more or less classifiable as

anarchist, including Peter Kropotkin, Noam Chomsky and Emma Goldman. These are

by the cartoonist Donald Rooum (b. 1926), who has been associated with the

Freedom Press since 1942. The bookshop’s persistence and its location

next to the Whitechapel Gallery, mean it has attracted the attention of

artists and curators beyond anarchist circles. For the Gallery’s Protest and

Survive exhibition in 2000 the artist Thomas Hirschorn built a temporary

enclosed bridge across the Alley from the Gallery to the temporarily removed

first-floor window of the Freedom Bookshop. In 2016 Wayward, a landscape,

art and architecture practice, collaborated with the Freedom Bookshop,

Whitechapel Gallery and Providence Row to create Literalley (a library in an

alley), seating, planters and a digital library in Angel Alley. Wayward

developed workshops with homeless clients and volunteers to build concrete

planters cast from a library of books. Embedded in the project are digital

recordings of interviews, stories and conversations, accessible only in the

alley. The planters are cared for by Providence Row’s residents and

staff.

Freedom’s activities have attracted more oppositional attention, from the

police up to the 1980s, and by political antagonists more recently. The shop

has been firebombed twice, in 1993 by the neo-Nazi group Combat 18, and in

2013 by unknown assailants, burning or water-damaging much stock and part of

the archive. Volunteer assistance saw the shop open again in days. Virtual

support of Freedom’s aims has included the digitisation of its archive of more

than a thousand issues of Freedom dating back to 1886. In 2015 a survey

revealed significant structural problems in the roof, walls and staircase of

No. 84B. Freedom has been fundraising for repair work.

Climbing the stairs

Contributed by michaelshade on May 23, 2017

My relative, Lewis Levin, was living here at the time of his death in 1927.

Lewis (Leibisch) Levin was a brother of my great-grandmother Mikhlya. He was

born in 1861 in Streshin, a little village on the river Dniepr, in what is now

the south-east of Belarus. In the early 1900s he came to London accompanied by

his three children from his first wife, who had died a few years previously,

and his second wife with her own daughter. They found somewhere to live in the

heart of the East End, where tens of thousands of East European Jews had

settled over the previous 20 years or so.

My own grandmother - Lewis' niece - came to London soon after, aged about 18,

and stayed with the Levins, probably helping to look after the children.

Within a couple of years there were two more boys, and they moved from one

accommodation to another, always along Whitechapel High Street and Mile End

Road, presumably to have more room for the expanding family. In every

document, and in various trade directories, Lewis is a 'Paper Bag Maker', even

sometimes a 'Master Paper Bag Maker'; his own children, and my own young

uncles and aunts, were all roped in to work in his paper bag factory, which

was mostly located on the kitchen table.

We knew that he had died in 1927, aged 67, and that he was probably living on

his own by this stage - his second wife had died when the boys were very

young, his older children had all left home for marriage, America, or the

Russian Revolution, and the younger boys didn't see their futures in paper

bags and left home to work elsewhere and to put themselves through night

school.

The figure of Lewis has long fascinated me, and a few months ago I ordered a

copy of his Death Certificate, to see if it could offer up anything new about

him. And so it did - an address: "of 84B Whitechapel High Street". So now we

knew where he had been living at the time of his death.

The next time I was in the area I looked for the building. Next to the

Whitechapel Library I found number 82; a few doors down was number 87. The two

or three buildings in between did not appear to be numbered, but I assumed 84B

would be one of them and duly took a photo as evidence.

My cousin Beatrice, Lewis' great-grand-daughter, is currently in London

visiting from the US. Beatrice's grandfather Sam had been involved in the

Workers' Circle, a friendly society established to further the interests of

working-class East European Jews, from the 1910s onwards, and her mother Alice

was active in the Yiddish theatre movement from the 1930s.

Yesterday afternoon Beatrice and I went on a 'Musical Walk round the Jewish

East End', organised by the Jewish Music Institute, and guided by the

historian David Rosenberg (highly recommended, by the way). The Workers'

Circle and Yiddish theatre both featured in David's programme for the walk.

The group met outside the Library, and then David led us off down a narrow

alleyway between two of the neighbouring buildings - Angel Alley. There on the

right a notice was pinned to a door: 'This is NOT 84B, it's 84A. 84B is

opposite!' You can hear the exasperation in the printed words. You can

probably also hear my involuntary intake of breath, for 84B turns out to be

the premises of Freedom Press, the long-established Anarchist publishers and

booksellers.

David was going to tell us about some of the radical figures and groups that

flourished in the area 100 years ago, but Beatrice and I were just standing

there, minds racing, staring at the building.

After the walk, we grabbed David for a chat over a superb falafel lunch, then

made our way back to see if the Freedom bookshop at 84B was still open. It

was. We explained why we had come, and asked the lady in the shop if she knew

how the building was being used in 1927. She kindly went off to find a book

containing a history of the organisation - and its premises - which told us

that at least before 1942 there had been a printing press occupying the ground

floor.

"Would you like to see upstairs?" I had to ask her to repeat the question,

partly because I don't hear very well, but mainly because I couldn't believe

what I had just heard. Upstairs? Lewis must have lived upstairs, 85 years ago.

We took a deep breath, and followed her up. The staircase, banisters, walls,

and some of the doors, looked as though they had had nothing done to them in

100 years or more.

She took us into one of the rooms, and we discussed the layout. The room we

were standing in had a structural beam across the middle, and we reckoned it

had probably originally been two rooms. On the landing there was a blanked-off

door which confirmed this.

So we sat, and stood, in one half of the room, looking out to the brick wall

opposite (the Library building, in fact), and tried to imagine a bed, and a

chair, and a table. Where was the sink? There probably wasn't one, he'd have

had to bring water in from the bathroom. Was there even a bathroom? How did he

cook? Did he cook?

But it was the stairs that got me. He must have gone up and down these stairs

every day for months, maybe two or three years. And here we were, treading the

same steps, holding on to the same worn banisters, knocking on doors - his

door, maybe - to feel the wood.

He fell ill here, and died at the London Jewish Hospital down the road in

Stepney Green. I've just looked at the Death Certificate again. He died on 20

October 1927. Just 85 years and one day before we came to visit him.