East One Building, 20-22 Commercial Street

1927-8 former factory building, with later top floor, converted to offices 2002-3, site of St Jude's church

St Jude's Church

Contributed by Survey of London on Dec. 13, 2018

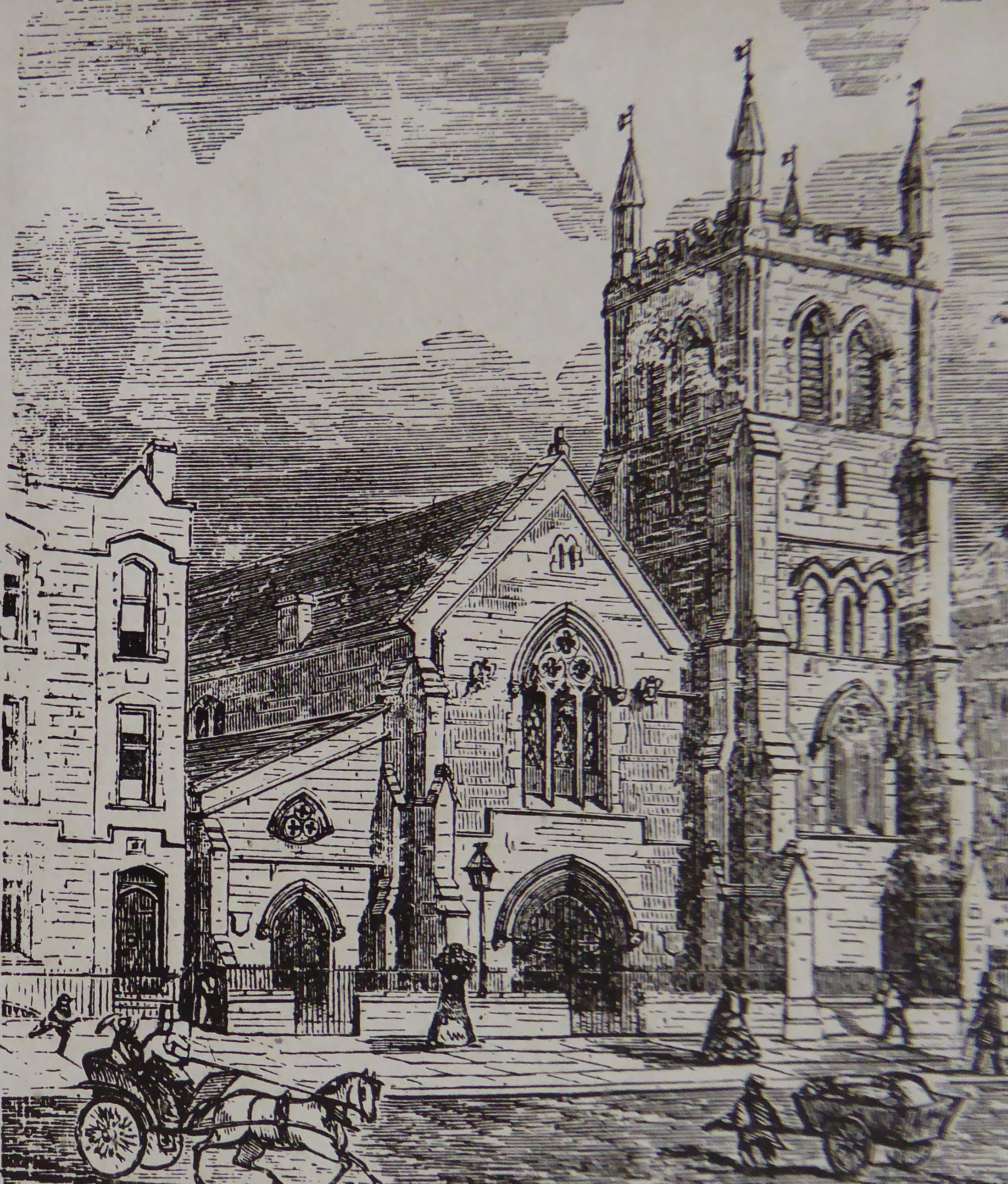

From 1847 to 1925 there stood on this site St Jude’s Church, a chapel of ease to St Mary Whitechapel, its creation a response to the growth in the local population. It was one of twelve new churches built in East London in the mid- 1840s, a project of Charles James Blomfield, Bishop of London from 1828 to 1856. It was one of the first sites on Commercial Street to be sold: the Commissioners for Building New Churches paid £1,520 for the 75ft frontage in December 1845.1 The design was a rather home-made, unarchaeological Early English Gothic, by Frederick John Francis, architect, whose 1841 book of church designs had earned the contempt of the Ecclesiologist: ‘Not one of them has any Chancel.. they are, in short, lamentable examples of what has been truly called “cockney Gothick” ’.2 The church, in brick with stone dressings, was built in 1846-7 by H.W. Cooper, of Regent Square, and consecrated in April 1848.3 It had a steeply pitched open timber-trussed roof, lower aisles separated by circular piers, a shallow chancel the full height of the nave with a reredos fronted by an arcade of seven trefoil-headed arches, a simple tripartite window above, and a 65ft batter-buttressed tower at the southwest corner, originally intended to have a spire.4 Although it was originally designed to have a single gallery at the west end, galleries on the north and south sides were added by Cooper in 1849.5

St Jude's church and vicarage

(left) in 1873

St Jude's church and vicarage

(left) in 1873

National Schools, a simple shallow two-storey building, stood to the rear of the church.

Equally unecclesiological was the first incumbent, Hugh Allen, appointed in April 1848, a ‘thoroughly evangelical clergyman’, who embraced Temperance as a cure for the ills of the poor, addressing vast open-air meetings in Victoria Park and Hackney Downs, and campaigning for street fountains.6

Though the later pastoral work of Samuel Barnett has come to dominate the history of St Jude’s, Allen was not idle away from the pulpit and the park. With the assistance of the rector of St Mary’s, William Weldon Champneys, who was involved in many Whitechapel initiatives to alleviate poverty, a Penny Bank was established at St Jude’s in January 1850. This was modelled on an initiative begun by John Scott in Greenock in 1847 ‘to create and foster provident habits’ among the poor by enabling them to open an account with the deposit of one penny, with interest paid on every pound saved, if deposited in regular weekly amounts.7 By 1858 Allen had set up a Young Men’s Mutual Improvement Society, which met on Tuesday evenings for improving discussions of Biblical topics.8

Allen’s additional appointment in 1859 as Afternoon Lecturer at St George in the East, however, saw his evangelical zeal stoke local opposition to the ‘Popish’ services of the Tractarian Rev. Bryan King, and a number of ‘ritualism riots’ there in 1859-60.9 Allen resigned his post at St George in the East in December 1859 at the height of the disturbances and preached his last sermon to his congregation at St Jude’s, ‘one of the largest in London’, in January 1860 when he was appointed to St George the Martyr, Southwark.10 Pastoral endeavours continued – a singing class, a branch of the East London needlewomen’s Institution, which took government contracts to employ poor needlewomen locally, and evening lectures and musical entertainments.11

In 1860 a narrow vacant strip of ground immediately to the north of the church on Commercial Street was bought for £615 from the Commissioners of Woods and Forests and a parsonage house built on it the following year. It of three storeys in an anaemic Tudor style, with two shallow-pointed pediments to the parapet. A sharp decline in St Jude’s congregation ensued after 1868 under Robert Haynes, however, who alienated the dwindling body of parishioners with Ritualist tendencies, but its fortunes bounced back under the tireless Samuel Barnett, curate at Bryanston Square, who was appointed Vicar in 1873, having requested a poor parish where he could do good: the Bishop of London fulfilled his wish, assessing it as the ‘worst parish in in my diocese, inhabited mainly by a criminal population’.12

St Jude’s was the crucible for most of the future social endeavours of Barnett and his wife Henrietta, including Toynbee Hall and the Whitechapel Gallery, but in the decade before these grander schemes took off, the church, vicarage and schools were the focus for smaller initiatives of improvement for the local population. Barnett instituted a mixed choir, and began a series of evening lectures on ‘great lives, adult classes in French, German, Latin and arithmetic, and the National Schools, which had been closed in the dwindling years of Haynes, reopened in 1874, with a playground created a few years later between the school, a tennis court, George Yard Buildings and neighbouring houses later occupied by St George’s House.13

The interior of St Jude's, looking east, after the removal of the galleries

Barnett was a missionary aesthete in the Ruskinian mould, believing that spiritual awakening would come not just from improved physical and educational conditions, but from beautified surroundings, domestic and urban. The cramped parsonage he found in a dilapidated state, beset by leaks and dry rot, and the church building,‘a cheap structure, built by cheap thought and in cheap material’.14 In a move that would have pleased The Ecclesiologist, a Faculty was secured for removing the galleries in 1874, the organ was repositioned and rebuilt by Willis of Minories under the direction of Henry Heathcote Statham (1839–1924), editor of The Builder, who went on to be the organist at St Jude’s. A frieze of growing corn and vine was painted over the communion table at the west end by Emily and Harriet Harrison, long-term assistants to Henrietta Barnett in her social work, and Henry Holiday lent large-scale drawings of angels to hang high up in the church.15 In 1879 William Morris produced a more radical and lively colour scheme for the interior: ‘East End: apple green stencilled in darker shade; curtains red and gold; pillars scarlet; dado for aisle walls of stronger tone; walls above stone; apple green around clerestory windows; abolish cornfield and hedge frieze,’ and photographs of ‘Italian and Spanish masterpieces’ were hung from the pillars and organ screen. This was carried out in 1883-4 under the direction of Charles Harrison Townsend, later architect of Whitechapel Gallery.16: The Barnetts did their best with the interior of the ‘small, dark’ vicarage, with its basement kitchen, easing the space problems with a single-storey bay to the front with a side entrance, and a side passage, to the designs of Ewan Christian in 1877. Inside was a haven of Aesthetic aspiration: the drawing room windows sported ‘primrose silk curtains against opal-coloured walls’, though there were ‘the small annoyances of greasy heads leaning against Morris papers’ when the poor of the parish came to call.17

In 1882 a brightly coloured drinking fountain was installed on the west tower on Commercial Street. It was used, according to Henrietta Barnett who had paid for it, by indigent locals to wash their clothes and utensils, and, on one occasion, a baby.18 Made of Doultonware ceramic, with steps by the Eureka Concrete Company, the materials were chosen as a robust material cheaper than granite; it had formed the centrepiece of Doulton’s exhibit at the 1882 Building Exhibition at the Agricultural Hall. Designed by Statham, it comprised a three-lobed bowl supported on three columns and backed by a semi- circular plaque proclaiming ‘With God is the Fountain of Life’.19 In 1884 Edwin Roscoe Mullins' large sculpture of Isaac and Esau, exhibited that year at the Royal Academy, was displayed in the church, which was later hung with similarly inspiring work by G.F. Watts. The same year a large mosaic version of Watts’s ‘grand but rather inexplicable’ painting of Time, Death and Judgment, executed by Giulio Salviati from a cartoon by Cecil Schott, was installed above the fountain, along with only moderately helpful plaques to explain the iconography. The unveiling ceremony was by Matthew Arnold, no less.20 Watts’s painting had been shown at the 1882 St Jude’s art exhibition, an annual event that Barnett had instituted in 1881 in the National Schools behind the church, and which were the precursor of the Whitechapel Gallery. The success of those exhibitions led to a three-storey extension in 1886 to the rear of the school with three well-lighted rooms for the shows which continued annually till the Whitechapel Gallery was opened in 1901.21 Pressures of increasing social work also saw a large top-lit reception room added to the rear of the vicarage in 1884.22

By 1888 attendance had dwindled to around 250 (under Allen it was said to have exceeded 1,000), and in 1893 Barnett, deeply occupied with work at Toynbee Hall and elsewhere, resigned as Vicar of St Jude’s, to be replaced in the role by his curate, Ronald Bayne.23 By then there were said to be only 120 Christian families in the parish and in 1923 the decision was taken to merge St Jude’s with the mother parish of St Mary Matfelon.24 The Church Commissioners put the church building and vicarage up for auction, with the stipulation that the buyer dismantle the building, which could not be reused for religious purposes, but only the vicarage sold.25 The Commissioners dismantled the church to make the site more attractive and it was sold by private treaty to Crosby Estates. Dame Henrietta Barnett wrote to The Times offering the Watts mosaic as a gift to whoever would place it to be seen by the ‘passer by’.26 The Revd Wilfred Davies of St Giles-in-the Fields, Bloomsbury, won the prize and the mosaic was salvaged and re-erected with repairs by the artist Boris Anrep on a prominent position on the wall of St Giles-in-the-Fields National Schools in Endell Street, Covent Garden, ‘a junction of five roads where the picture could be seen by thousands every day’. After that building closed as a school, the mosaic was removed in 1970 and reinstalled on the staircase of the south porch of the parish church of St Giles in the Fields.27 The Doulton fountain from St Jude’s was also said ti have been salvaged, and possibly relocated to a Stepney school. If it survives, its present location is unknown.28

The new parts of the St Jude’s National Schools building behind the church had become an adjunct of Commercial Street Schools (later Canon Barnett School), the ground floor in use as a gym by 1936; the older portion of the schools was used as a club after the First World War and offices by 1936, and the whole was demolished c. 1937 after Toynbee Hall had acquired the site to_ _ build their theatre.29

When the church was demolished the vicarage became Jack Seres, gown manufacturers, with further premises at 48 and 50 Commercial Street, remaining till the building was damaged beyond repair during the war. Profumo House was later built on the site.30

-

Twenty Third Report of the Commissioners of Her Majesty’s Woods, Forests, Land Revenues, Etc, London 1846, p. 77: London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), DL/A/C/MS19224/348 ↩

-

The Ecclesiologist, 2, 1843, pp. 73-4 ↩

-

LMA, District Surveyor's Returns (DSR); DL/A/C/MS19224/348: Morning Advertiser, 18 April 1848, p. 2: Builder (B), 22 April 1848, p. 201 ↩

-

The National Archives (TNA), IR58/84840/5730: Gordon Barnes, Stepney Churches: An Historical Account, London 1967, pp. 91-2 ↩

-

DSR: LMA, P93/JUD/7, 8 ↩

-

John Bull, 22 April 1848, p. 6: Gentleman's Magazine, June 1848, p. 654: Bell’s Weekly Messenger, 21 Feb 1853, p. 5: Essex Standard, 6 Aug 1856, p. 2: Armagh Guardian, 7 Nov 1856, p. 5: Marylebone Mercury, 25 Sept 1858, p. 4 ↩

-

The Globe, 25 July 1850, p 1: Sampson Low, The Charities of London, London 1850, pp. 177-8: Samuel Couling, The Labouring Classes: Their Intellectual, Moral and Social Condition Considered, London 1851, pp. 85-93 ↩

-

East London Observer (ELO), 27 Feb 1858, p. 4 ↩

-

Edward Francis Russell, ed., Alexander Heriot Mackonochie, a Memoir by E.A.T., London 1890, pp. 55-58: Morning Chronicle, 17 June 1859, pp. 6-7: E_vening Mail_, 26 Sept 1859, p. 6 ↩

-

Morning Advertiser, 9 Dec 1859, p. 4: London Evening Standard (LES), 23 Dec 1859, p. 3: Shoreditch Observer, 21 Jan 1860, p. 2: Daily News, 23 May 1860, p. 2: Illustrated London News (ILN), 14 May 1864 ↩

-

ELO, 27 Oct 1860, p. 1; 3 Nov 1860, p. 2; 13 Dec 1862, p. 2; 14 May 1870, p. 5 ↩

-

LMA, DL/A/C/MS19224/34; F/BAR/1 ↩

-

Henrietta Barnett, Canon Barnett: His Life, Work and Friends (Canon Barnett), London 1918, vol 1, pp. 73-5: LES, 23 Nov 1878, p. 3: Samuel Barnett, St Jude’s Commercial Street, Whitechapel: Pastoral Address and Report for the Year 1881-82, London 1882, pp. 14-15: Samuel Barnett, St Jude’s Commercial Street, Whitechapel: Pastoral Address and Report for the Year 1884-85, London 1885, p. 18 ↩

-

LMA, DL/A/C/MS19224/34: Canon Barnett, vol 1, p. 68: St Jude’s Whitechapel… Report (1884-85), quoted in Lucinda Matthews-Jones, ‘Sanctifying the Street: Urban Space, material Christianity and the Watts Mosaic in London, 1883 to the Present Day, in Material Religion in Modern Britain: The Spirit of Things, ed. Timothy Willem Jones and Lucinda Matthews-Jones, New York 2015, pp. 57-74 ↩

-

Canon Barnett, vol. 1, pp. 218, 221: ELO, 17 July 1875, p. 6: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography sub Statham ↩

-

DSR: Canon Barnett, vol. 1, p. 218: Samuel Barnett, St Jude’s Commercial Street, Whitechapel: Pastoral Address and Report for the Year 1883-1884, London 1884, pp. 10-11: Samuel Barnett, St Jude’s Commercial Street, Whitechapel: Pastoral Address and Report for the Year 1884-1885, London 1885, p. 9 ↩

-

LMA, DL/A/C/MS19224/34: Canon Barnett, vol. 1, pp. 152-3 ↩

-

Canon Barnett, vol. 1, p. 221 ↩

-

B, 23 Sept 1882, p. 396: The Artist and Journal of Home Culture, 1 Oct 1882, p. 316 ↩

-

Samuel Barnett, St Jude’s Commercial Street, Whitechapel: Pastoral Address and Report for the Year 1884-85, London 1885, pp. 9, 12-13: B, 2 Aug, 1884, p. 160; 30 Aug, p. 285; 6 Dec 1884, p. 753: Mathews-Jones, op. cit., pp 66-8: The Salviati Architectural Mosaic Database ↩

-

Canon Barnett, vol. 2, p. 156: ELO, 17 April 1886, p. 6 ↩

-

DSR: TNA, IR58/84809/2690: Goad insurance plans: Canon Barnett, vol. 1, p. 152 ↩

-

Canon Barnett, vol. 1, p. 283 ↩

-

Church of England Record Centre, BARNES 3/2/3/14 ↩

-

Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives (THLHLA), B/ELL/2/8; LC6874 ↩

-

LMA, LMA/4063/006 - ‘The quasi-autobiography of Dame Henrietta Barnett by her assistant Marion Patterson’, c. 1937 ↩

-

Matthews-Jones, op. cit., pp. 61-2 ↩

-

THLHLA, notes on verso of P10169 ↩

-

TNA, IR58/84840/5730; IR58/84809/2690: LMA, GLC/AR/BR/36/002740 ↩

-

Post Office Directories ↩

East One

Contributed by Survey of London on Oct. 18, 2018

Nos 20-24 Commercial Street is a red-brick-faced steel-framed former factory and warehouse building put up in 1927-8 to the designs of Trehearne & Norman architects on the site of St Jude’s church. With vestigial classical details – stone cornice and first-floor window surrounds - it was built as a speculation by Marcus Estates Ltd, who had acquired the site from Crosby Estates Ltd of Bishopsgate, purchasers in 1925 of the site from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners.1 In 1929 the building was acquired and occupied by Ellis and Goldstein Ltd, manufacturers of coats and costumes, and furriers, with branches in Manchester, Dublin, Glasgow and the City of London, who stayed till 1959 when David Barnes, knitted goods manufacturers, a subsidiary of Courtaulds, moved in, to be replaced by Ematex Ltd in the 1970s and 1980s.2 In 2002-03 the building was converted to offices, extended to the rear, and given a fifth floor by the Aitch Group to the designs of Buckley Gray architects.3 It has been occupied since as East One, largely by companies involved in a variety of tech industries.

-

London Metropolitan Archives, District Surveyor's returns: Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives (THLHLA), uncatalogued building control files 12422 and 12443; LC6874; B/ELL/2/8 ↩

-

Post Office Directories: THLHLA, uncatalogued building control file 12422 ↩

-

Tower Hamlets planning applications online ↩