part of Calcutta House

1962 former tea warehouse, site of St Paul's German Reformed Church, later part of Calcutta House, London Metropolitan University | Part of London Metropolitan University buildings

Wentworths and Woodlands

Contributed by Survey of London on Feb. 24, 2017

Although much has been made of the genteel character of suburbs further east, sixteenth and seventeenth century Whitechapel was not without its own collection of gentlemanly citizens and, it seems, their correspondingly grand houses. Resident in the area from c.1570 – 1678 as Whitechapel experienced the beginnings of the mixed urbanisation that was to characterise it for much of the succeeding centuries, three consecutive ‘William Megges’ (or Meggs) invested the profits from their successful mercantile ventures locally. The Megges family involved themselves in personal building projects as well as significant benefactions to the parish. They were most notably active in the development of a large site between Whitechapel High Street and Wentworth Street called the ‘Woodlands’ and in the construction and occupation of a mansion house on this land.1

Earlier held by the monastery of Stratford Langthorne, the Woodlands was an eight-acre plot with its own fraught history, with only part of which the Megges’ were to become implicated. Its extents were defined by present-day Middlesex Street on the west, Wentworth Street to the north, Commercial Street to the east and Whitechapel High Street to the south. After falling briefly into the hands of Bishop Nicholas Ridley, the site was confiscated by Edward VI in 1550 and gifted to the courtly Wentworth family as part of the establishment of their extensive Stepney manor. Under the Wentworths, the Megges came to occupy and transform the centre and south-facing edge of the Woodlands, but their acquisition of this land transpired in a typically piecemeal fashion - a reflection of the difficulties inherent to the continuation of the ancient manorial copyhold system of tenure. In spite of growing pressure to switch to a leasehold pattern of land-holding, it appears that the Wentworths resisted administrative and legal changes in their manorial estate for as long as possible, leading to the ever more complicated fragmentation of leases and confusion over responsibilities for maintenance of the same. Smith noted in his early history of Stepney that this “loose and primitive” system of land tenure was increasingly incompatible with the new economic forces acting in the area and impeded development.2

Led by former Lord Mayor and Mile End resident Sir John Jolles, in 1617 a co- ordinated challenge against the Wentworths’ inflexibility was launched by copyholders from across Stepney manor. The uprising focussed on the lack of security afforded to this group of copyholders as well as the customs and fines imposed on them which, it was claimed, dissuaded longer-term investment in the manor. In an agreement lodged in the Chancery Court, the Wentworths conceded that these copyholders could henceforth continue in and also re- assign their leases at their own discretion in perpetuity, subject to customary renewal periods of up to thirty-one years (and increasingly a formality in all but name). This shift in policy allowed for greater stability. Beginning as leaseholders, it was however in the years preceding this agreement that the Megges’ acquired and consolidated their family estate in Whitechapel, having successfully negotiated the knotty sixteenth-century tenurial landscape to their advantage. Such success may support archivist Mark Ballard’s recent observation that there were ways and means around convoluted manorial customs and that the lords of Stepney were no strangers to corrupt practices.3

-

D. Morris, Mile End Old Town, edn. 2007, pp.1-2 ↩

-

'Stepney: Manors and Estates', A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 11, Stepney, Bethnal Green, ed. T F T Baker, 1998, pp.19-52; H. Smith, History of East London, 1939, p.51; D. Morris, Whitechapel 1600–1800: a social history of an early modern London inner suburb, 2011, pp.3-5 ↩

-

Strype, Survey of London, 1720, Book 4, Chap. 5, [online: https://hrio nline.ac.uk/strype/strype/TransformServlet?display=normal&page=book4_086]; 'Stepney: Manors and Estates', A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 11, Stepney, Bethnal Green, ed. T F T Baker, 1998, p.19-52; M. Ballard, Copyhold in Whitechapel, [Online: https://surveyoflondon.org/blog/2016 /copyhold-whitechapel/] ↩

Constructing ‘Megses Glorie’

Contributed by Survey of London on Feb. 24, 2017

Regarding the Whitechapel area in 1598, John Stow described a steep upward curve of building just outside London’s city walls to the east. He noted that over the past forty years a few scattered tenements stretching out from Aldgate had transformed into streets “fully replenished with buildings” but also “pestered with diverse alleys”. Stow reported that Houndsditch and Whitechapel possessed “fair hedgerows of elm trees”, numerous garden houses, tenter yards, bowling alleys and small cottages. Considering several large new-built houses in Stepney, he recited the rhyme: “Kirkebyes Castlee, and Fishers Follie, Spinilas pleasure, and Megses glorie”. The final item on this list likely reflected the house of the first William Megges, built in the Woodlands at the end of the sixteenth century and named the ‘Harte’s Horne’.1

As one of many newly wealthy City men who saw potential in the open fields of the semi-rural east, William Megges c.1527 – 99 in fact began his apprenticeship in the trade of drapery in Flanders under Thomas Hough in 1541 and obtained his freedom from the Drapers’ Company of London in 1548. Thereafter he set up his household and practised his trade in London. He took on eleven apprentices between 1551 and 1581 and rose to become Warden of the Company three times between 1572 and 1583. Clearly becoming more engaged in transnational mercantile activity in this period, his name consistently appeared in the port books of London in relation to the importation of wainscots, hops, oil and soap ashes from the Low Countries in the late 1560s. In 1570, he gave notice to his Company that he was concerned no longer with the retail of drapery and instead was solely focussed on the mercantile trade. He also obtained membership of the Merchant Adventurers. His son (William Megges II, born c.1557) was made free of the Adventurers by patrimony in 1578. In a reflection of his success and social ambition, Megges I was granted a coat of arms in 1579.2

It was during these years of growing personal prosperity that Megges entered the Whitechapel property market. In July 1566 he sold three houses on the south side of the High Street “near unto the church” to a fellow citizen, Thomas Wilson. Taxations suggest his occupancy before he requested to be taxed as a resident of the City parish of St-Dunstan-in-the-East in 1567. Megges returned to Whitechapel in 1577, acquiring copyhold tenure of a parcel of land that came to be known as the ‘great garden’, located at the centre of the Woodlands, from the Pooley (or Poley) family, the copyholders under the Wentworths. However Megges did not immediately seek to occupy this site. Rather, like his predecessor, the gardener John Myllian, the merchant allowed the cultivation and development of the marshy land by a string of sub-tenants. The unchecked construction of sheds and tenements by these numerous individuals led to complaints from the Pooleys that over-building on the land had precipitated a decline in its condition. The Pooleys held Megges accountable for what they regarded to be many “decayed” buildings. The dispute, recorded in Chancery, fell in favour of Megges, who argued his willingness to complete remedial work was hindered only by his inability to gain access, barred from entry by his sub-tenants and their sub-tenants below them. He won the right to give over his responsibility for these properties to the sub-tenants themselves, but the nuisance caused by this episode doubtless had its effect.3

On renewing his lease in 1593, Megges elected to aggregate the smaller plots held by an array of sub-tenants to form a large garden for his own use. Around this time he also acquired a claim to two adjacent pieces of ground to the south and south-east. A patchwork of acquisitions and related building activity in the 1590s seems to have coincided roughly with Megges’ term as Master of the Drapers’ Company in 1590, an increasingly burdensome and expensive office at the time. He turned his attention to the creation of a mansion house and garden appropriate for his elevated position. By 1595 he had completed the building of the ‘Harte’s Horne’ and let part of it to a fellow guildsman, Richard Blounte. The scale of the new mansion house was indicated by its high rental value. Blounte rented the newly erected “great messuage or tenement” for £30 a year. In addition, Blounte paid £5 more to Megges for the six-roomed gatehouse constructed over an entry “in such sort as the same messuage and other premises were lately severed, repaired and builded by the said William”. Megges also built another smaller annexed house on recently purchased land to the east. This was profitably sub-let in 1599 to Kilbert Kirkby for £8 p.a. Further substantiating his occupation of the Woodlands, in 1596 Megges purchased the freehold for the plot of land on which the main part of the Harte’s Horne was built from other merchants. The freehold of the land under the gatehouse, which faced directly onto Whitechapel High Street on the site now nos 133 – 137), was separately purchased from Leonard Summersett sometime before 1598.4

According to Ogilby and Morgan’s map of 1676, the Harte’s Horne followed an old-fashioned courtyard plan. Principal rooms, probably in the inner range, were wainscoted and furnished with hearths, arranged alongside numerous secondary service spaces around a paved quad hidden from the high street behind the tall gatehouse and entry. Of especial note, the wainscoted great parlour was embellished with “nine painted stories”; panelling and painting in all costing £23 8s in 1595. A small closet chamber contained important household documents, whilst a larder, buttery and a cellar were lined with wooden shelves and settles. The great chamber situated above a ground floor hall was furnished with green saye (fine woollen cloth) curtains and valances, a white Irish rug, a Cyprus press, a great Dansk chest and a high status “great looking glass”. Likely located looking out northwards towards the gardens, there was a fashionable gallery where the family’s pictures of William Megges I and Queen Elizabeth were likely displayed. Two large projecting bay windows to the rear also took advantage of this pleasant situation and are discernible on the 1676 plan.5

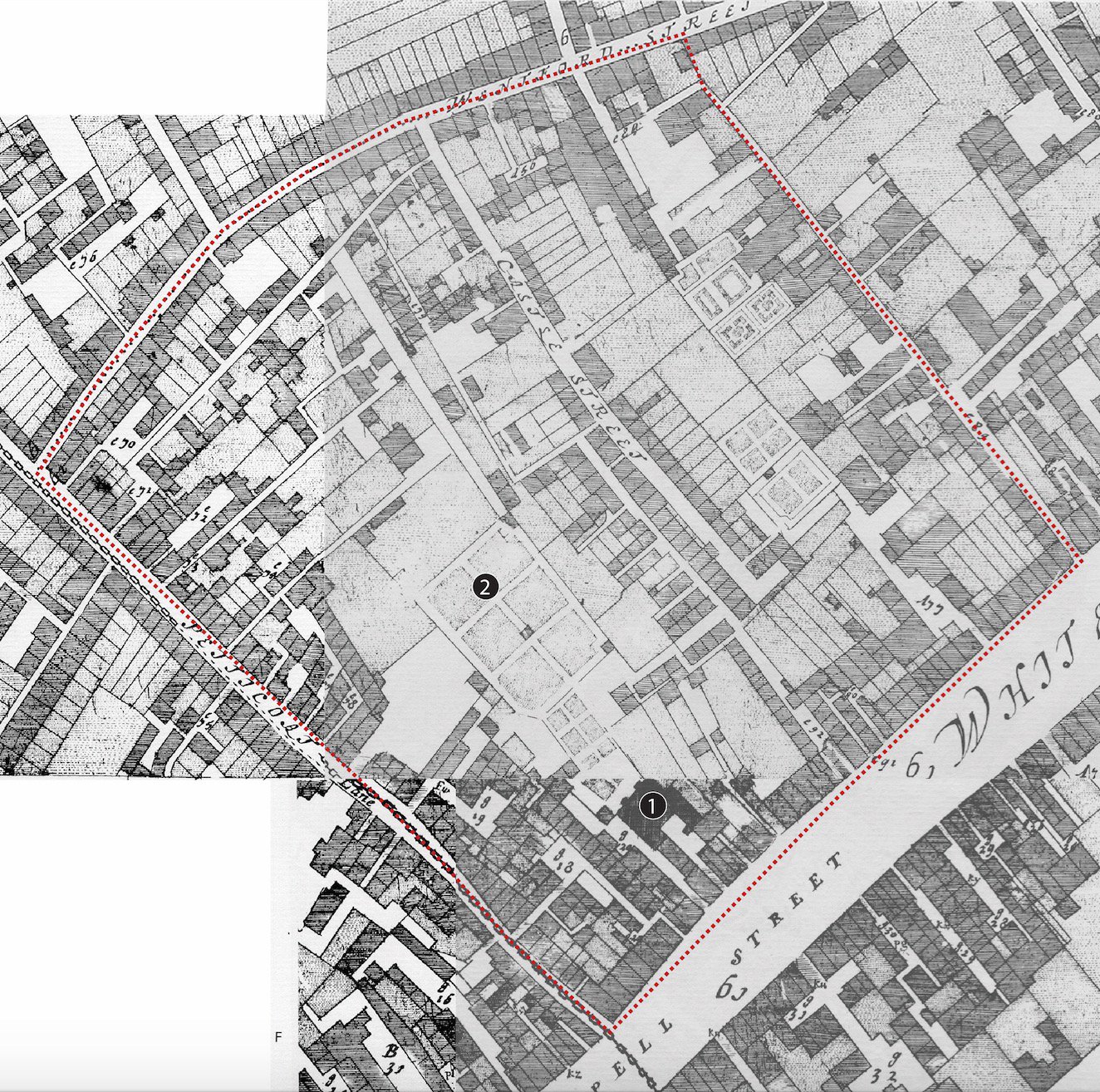

'Woodlands' marked on Ogilby and Morgan map of 1676. No. 1 relates to the Harte's Horne. No. 2 is indicative of the great garden.

Beyond the house to the north, a stable divided a smaller garden directly adjacent to the main house from the brick walled great garden nestled centrally on the Woodlands site. Within the walled garden, perimeter walks were unusually “set on either side with sycamore trees” and the north-eastern corner was occupied by a bowling alley, orchard and wainscoted banqueting house. A narrow strip of land, named the “long walk”, was lined with elms and extended right up to Wentworth Street. So taken was Megges with his newly created walled garden and its pleasures, that he included a special clause in Blounte’s 1595 lease to ensure continued access for himself, his wife and their friends, regardless of the extent of his occupation of the main house that was apparently variable, Megges having also purchased lands in Essex and beyond. Privileged associates were allowed to “walk and take their recreations therein, and to bowl in the bowling alley” as well as enjoy half of the garden’s “all manner of fruit coming, growing and yearly increasing upon the fruit trees standing and growing and to be growing”. Megges still however kept one eye on business, and appears to have allowed, if not encouraged, the noxious manufacturing of soap on his land by a handful of remaining sub- tenants. Soap-houses on the Woodlands site were referred to directly by Megges in his will and “rooms, vaults, pans, boilers, profits, commodities, enrolments and implements for soap-boiling” in the tenure or occupation of Thomas Bromefiled and George Hubberstie were excluded from a later lease of his lands. This was far from unusual for the area. A wave of local cottage industries using progressively more sophisticated processing techniques (e.g. glass-works) were taken up and expanded in the eastern suburbs during these decades.6

William Megges the elder, ‘Draper of Whitechapel’, died in 1599 a well- regarded gentleman. From the early 1540s until his death, he had bound himself to the Drapers’ Company socially and professionally and made generous bequests of plate and leases to the Company in his will. On condition of attendance at his funeral, mourning parishioners, friends and Drapers drank ale in the courtyard and rooms of the Harte’s Horne before processing to St Mary Matfelon in a show of honour and respect. Megges’ widow, Elizabeth Keathe (m. 1594), his third wife, was granted occupation of the Harte’s Horne. In the main, his eldest son, William Megges the younger, inherited most of the rest of his property, including the manor of Cockermouth, other plots in Wakering and Barking and leasehold tenements in Fetter Lane.7

-

Stow, Survey of London, ed. Kingsford, Vol. I, p.127; Ibid. p.166 ↩

-

A. H. Johnson, A History of the Worshipful Company of Drapers, 1914-1922, Vol. II, p.179; P. Boyd, Roll of the Drapers’ Company of London, unpublished notes, 1934; The Port and Trade of Early Elizabethan London: Documents, ed. B. Dietz, 1972; H. Dethick and W. Ryley, The Visitation of Middlesex, began in the year 1663, 1820, p.39 ↩

-

LMA, ACC/0903/146/A; TNA, E 115/268/136; H. Berry, The Boar’s Head Playhouse, 1986, p.15; TNA, C 3/227/19 ↩

-

TNA, PROB 11/93/133; A. H. Johnson, A History of the Worshipful Company of Drapers, 1914-1922, Vol. II, p.472; THLALA, P/SLC/1/17/45; THLHLA, P/SLC/1/17/11; P. Boyd, Roll of the Drapers’ Company of London, unpublished notes, 1934 ↩

-

TNA, PROB 11/93/133; THLHLA, P/SLC/1/17/45 ↩

-

TNA, PROB 11/93/133; THLHLA, P/SLC/1/17/45; TNA, C 14/256/34; P. Earle, The Making of English Middle Class, pp.25-27; A. Mukherjee, Penury into Plenty: Dearth and the Making of Knowledge in Early Modern England, 2014, pp.118-119; D. L. Munby, Industry and Planning in Stepney, 1951, pp.19-19 ↩

-

TNA, PROB 11/93/133; 'Wills: 41-45 Elizabeth I (1598-1603)', Calendar of Wills Proved and Enrolled in the Court of Husting, London: Part 2, 1358-1688, ed. R R Sharpe, 1890, pp.725-730; P. Boyd, Roll of the Drapers’ Company of London, unpublished notes, 1934 ↩

William Megges the younger and William Megges III

Contributed by Survey of London on Feb. 24, 2017

William Megges the younger (c.1557 – 1621) took possession of the Harte’s Horne on his mother’s death in the first decade of the seventeenth century. By this time the younger Megges had been widowed twice. He married for a third and final time in 1599 to Judith Cambell (c.1579 –1662), daughter of Sir Thomas Cambell, Lord Mayor of London. Like his father, Megges the younger was an active member of the Drapers Company, citizen of London and adventurous merchant. Between 1601 and 1611 he served as Company Warden three times, successfully trained at least four apprentices and remained an Assistant until his death. Notably however, he avoided serving as Master of the Company. Neither did he concern himself with civic governance, aside from a few stints on specialised advisory committees. Rather, Megges focussed his energies on trading companies. He was an early investor in the East India Company contributing £240 to become an ‘adventurer’ in this new commercial endeavour alongside other prominent London merchants. He was also apparently determined to build on his father’s legacy in Whitechapel. As a result, Megges the younger consolidated his claim to the family’s lands through the purchase of additional moieties and an extension to the freehold of another parcel of land to the south of the great garden and adjacent to his dwelling house, securing long-term tenure of 1000 years from Sir Thomas Bodley in 1610.1

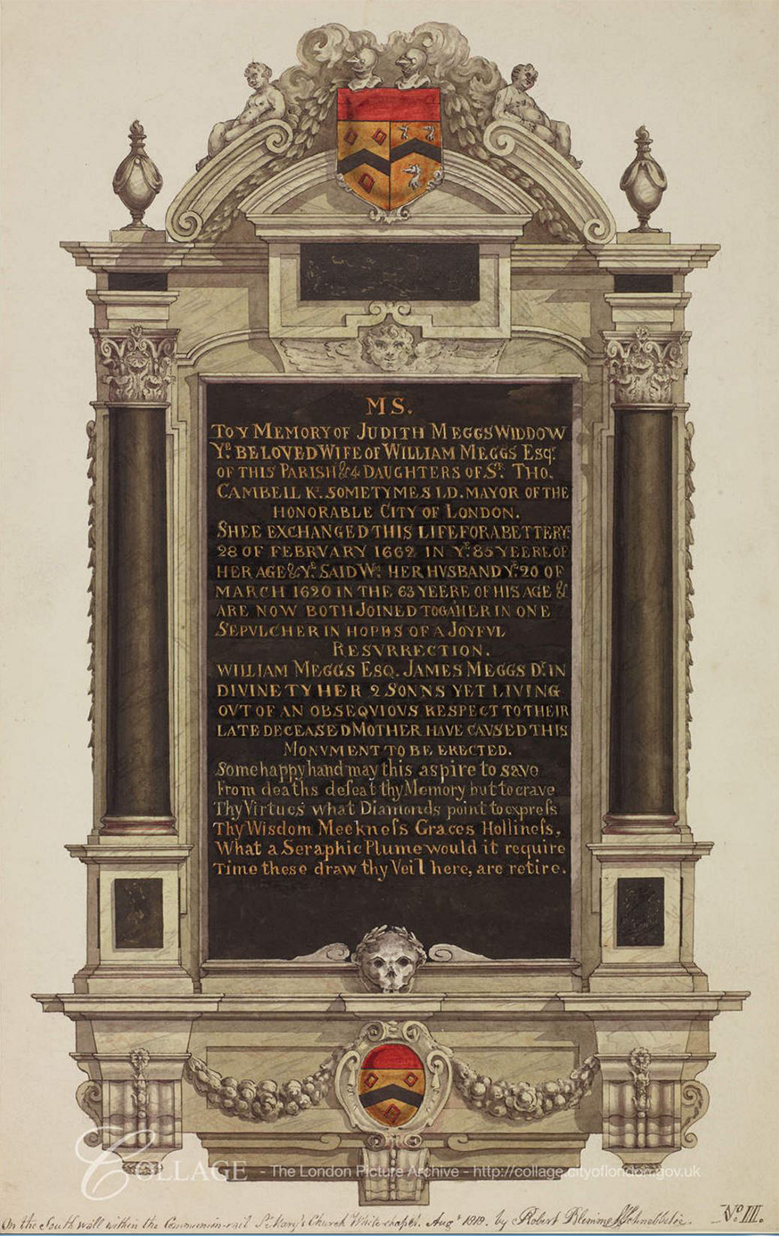

The family maintained a close association with the parish of St Mary Matfelon in the decades that followed. Regarded as one of the “most sufficient” parishioners and inhabitants of Whitechapel, Megges was appointed a vestry-man in 1615. After his death, his eldest daughter Judith married the minister of the church, John Johnson, a puritan who later aligned himself with the Laudian cause and lodged at the Harte’s Horne in the 1650s before being reinstated as rector. Although Megges’ first son Thomas died in the 1620s, his second, the inevitable William Megges III (1616 - 1678), was regarded a “gentleman of quality” and served as a parish vestry-man like his father. His third son, James, became a Doctor of Divinity and was ejected from his Surrey parish for Royalist (and possibly Laudian) sympathies in the 1640s. William Megges the younger was buried in the church of St Mary Matfelon. His wife Judith lived on until 1662, aged eighty-three. Soon after, the couple’s two surviving sons, William and James, erected a funerary monument honouring their parents’ patronage of the church. Made of black and white marble with Corinthian columns and a pediment, the tablet was mounted on the chancel wall and adorned with the family crests.2

Memorial to William Megges the younger in St Mary Matfelon, Whitechapel. Watercolour by Robert Blemmell Schnebbelie, 1818. (LMA, Collage 22631)

The Harte’s Horne consequently passed to William Megges III. In 1666, the main house had fifteen hearths, marking it as the largest dwelling house in Whitechapel. Seemingly conceived at the outset as a collection of houses with rental potential, subsidiary accommodation continued to be occupied by a series of respectable tenants. For example, in the 1660s the secondary annex claiming ten hearths was designated to Thomas Giles, ‘Mariner of Whitechapel’, and another of six hearths to William Paggett, a Baker. In the years immediately after the Great Fire of 1666, the value of land around London rose to unusually high levels. Much urban housing for the mercantile and professional middling-classes was lost amid the destruction and perhaps Megges saw in this moment an opportunity to further sub-divide his property to capitalise on the demand. His will of 1678 certainly made it clear that the Harte’s Horne had been divided into “several houses” occupied by nine separate tenants, and was additionally linked to three adjoining tenements as well as “one long warehouse and two vaults”. Megges was also connected to lands in Westminster, profitably farming fifty tenements from the 1640s.3

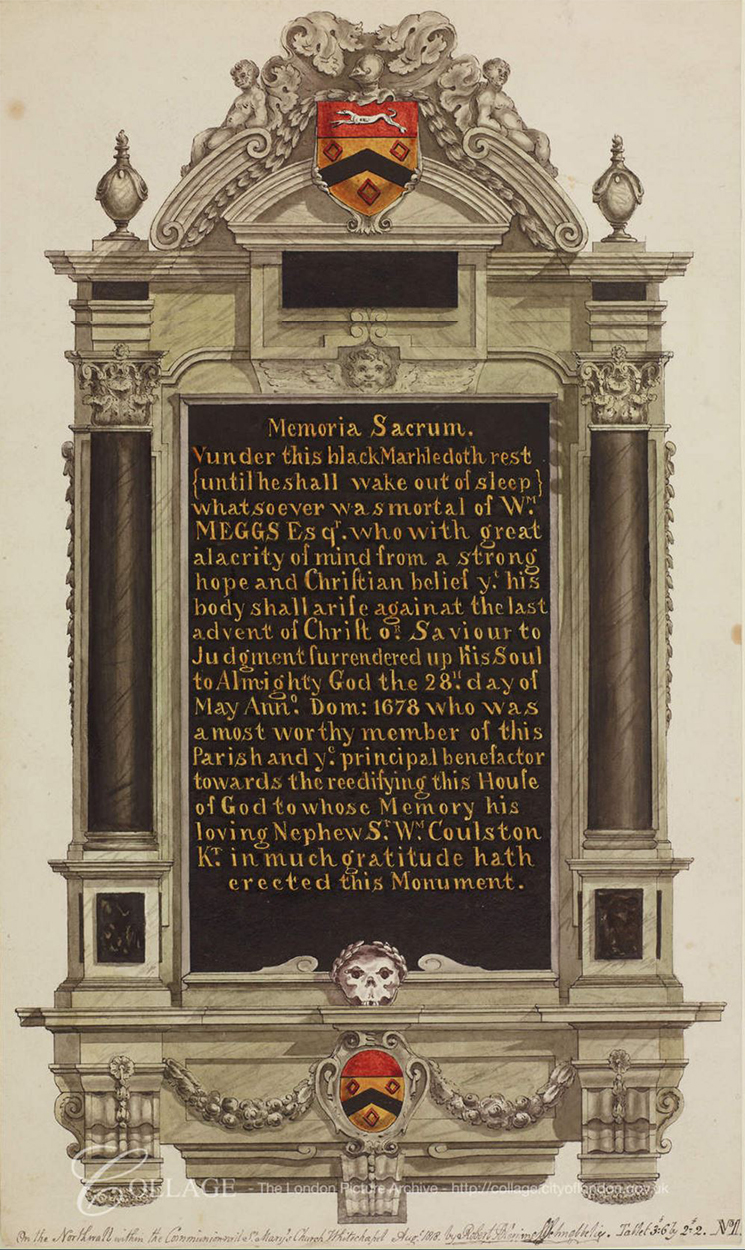

As an early backer of the East India Company ventures, Megges the younger passed onto his son stock valued at £600, as well as a further £1600 invested in later adventures, although executors of his will were instructed to pay off any outstanding debts from this sum. Megges III proved to be generous with this inherited fortune. Unmarried and with no direct descendants, he supported the construction of almshouses for twelve elderly parishioners. Situated on Whitechapel Road and opened in 1658, he also gifted pension sums to provide for living costs. The final Megges of Whitechapel was also regarded “the principal benefactor” of the rebuilding of St Mary Matfelon in 1672-3. Fittingly, on his death in 1678, William Megges III was buried alongside his parents in the parish church. His own funerary monument, funded by his nephew and inheritor, (Sir) William Goulston, matched that of his parents in form and appearance. These twin black stones marked the effective end of over a century of the Megges family in Whitechapel.4

Memorial to William Megges III in St Mary Matfelon, Whitechapel. Watercolour by Robert Blemmell Schnebbelie, 1818. (LMA, Collage 22632)

-

TNA, PROB 11/138/59; 'Dagenham: Introduction and manors', A History of the County of Essex: Volume 5, ed. W R Powell, 1966, pp.267-281; H. Dethick and W. Ryley, The Visitation of Middlesex, began in the year 1663, 1820, p.39; P. Boyd, Roll of the Drapers’ Company of London, unpublished notes, 1934; '1582 London Subsidy Roll: Broad Street Ward', Two Tudor Subsidy Rolls for the City of London, 1541 and 1582, ed. R G Lang, 1993, pp.169-176; A. H. Johnson, A History of the Worshipful Company of Drapers, 1914-1922, Vol. IV, p.417; Ibid, p.450; Ibid, p.21, fn.3; ‘East Indies: April 1601’, Calendar of State Papers Colonial, East Indies, China and Japan, Volume 2, 1513-1616. ed. W N Sainsbury, 1864, pp.123-126; THLHLA, L/SMW/D/6/1 ↩

-

TNA, E135/23/78; 'Middlesex Sessions Rolls: 1662', Middlesex County Records: Volume 3, 1625-67, ed. J C Jeaffreson, 1888, pp.318-331; A. R. Bax, ‘The Plundered Ministers of Surrey’, Surrey Archaeological Collection, Vol 9, 1858, pp.290-295; LMA, Collage 22631 ↩

-

H. Smith, History of East London, 1939, p.58; D. Morris, Whitechapel 1600–1800: a social history of an early modern London inner suburb, 2011, p. 4; TNA, PROB 11/356/609; TNA, PROB 11/440/434; D. Keene, P. Earle, C. Spence and J. Barnes, 'Middlesex, St Mary Whitechapel, Street Side', Four Shillings in the Pound Aid 1693/4: the City of London, the City of Westminster, Middlesex, 1992, [Online: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series /london-4s-pound/1693-4/middlesex-street-side-19]; ‘Cases brought before the committee: January 1646’, Calendar, Committee For the Advance of Money: Part 2, 1645-50, ed. M A Everett Green, London, 1888, pp.667-678 ↩

-

TNA, PROB 11/138/59; R. Wilkinson, Londina Illustrata, 1825, p.92; TNA, PROB 11/356/609; 'Stepney', An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in London, Volume 5, East London, 1930, pp.69-101; LMA, Collage 22632 ↩

The Goulston Estate, 1678-1776

Contributed by Survey of London on March 2, 2017

Son of William Megges III’s younger sister Alice, Sir William Goulston (c.1641-1688, knighted 1680) became a London merchant and active committee member of the Royal African and East India Companies, following the pattern set by his mother's forefathers. Goulston’s industriousness was recognised by his uncle William, who not only entrusted him with his wealth but the management of his Whitechapel almshouses too, demonstrating the “trust and confidence” Megges placed in his sister’s eldest son. Goulston served twice as an MP, once for Bletchingley in 1681 and another for New Romney in 1685, acquiring lands in Norfolk and in Kent through his wife, Frediswed née Morris.1

Regarding the Megges’ Whitechapel property, between his inheritance in 1678 and his death in 1688, Goulston was responsible for a major redevelopment of the site. Contemporary with the planning of the mercantile Wellclose Square to the south, it was in this substantial re-organisation and densification that the Harte’s Horne of the 1590s was destroyed. In its place two lines of terraced houses were erected along what was once known as ‘Boar’s Head Alley’, re-named ‘Goulston Street’ at this juncture. Goulston himself relocated to a house at the south-west corner of the newly created enclave which was accessible only from Whitechapel High Street via a wooden gate. The scheme was however incomplete until a second phase of building beginning c.1690 formed Goulston Square, an arrangement of well-appointed houses gathered around a rectangular quad. This cluster ‘topped’ Goulston Street to the north and partly occupied the former great garden of the Megges family. Goulston Square housed twenty-nine inhabitants in 1693/4 and by Hawksmoor’s 1712 speculative proposal for a church situated to the east of the new square, several blocks of houses had been apparently realised. By 1740, forty modest houses had been constructed with around fifteen of these assigned to the square. One of these was Mr Cowley’s Snuff House, a reflection of the relatively polite character of the square and its occupation by a number of middling-sort merchants. The south-east corner of the street, once the heart of ‘Megges’ Glory’, became the ephemeral ‘Rummer Tavern’. Daniel Pincot made artificial stone from the east side of Goulston Street briefly around 1768.2

William Goulston’s early death at the age of forty-six prompted a series of legal cases between his widow, son and two daughters as disputed claims to his estate were resolved. His lands in Whitechapel and Norfolk were passed over to Frediswed, his widow and sole executrix, who remarried another prosperous MP, Sir James Etheridge. Goulston’s various other properties in Kent were willed to his son Morris alongside his substantial stock in the East India Company. As it transpired, Morris agreed to hold the £5000 portions assigned to each of his sisters, Frediswed and Mary, in trust until their eighteenth birthday in return for his mother’s inherited claim to the lands and rents in Norfolk. Goulston’s only son seems however to have faltered in this task and found himself unable to extract the funds he had invested elsewhere, leading his mother and two sisters, alongside their husbands, to seek resolution in an Act of Parliament of 1703. This Act approved special dispensation for Morris to sell freehold and leasehold land in Kent in order to settle his debt to his sisters but the litigation was long running. The settlement confirmed a substantial family painting collection housed within his mother Frediswed’s house in Whitechapel, presumably that formerly of her husband on Goulston Street, and passed to Morris on his mother’s death in 1735. The Whitechapel estate too duly fell to Morris and it appears he was active in encumbering the newly built tenements and dwelling houses in a number of mortgages from the 1720s. Morris himself was survived by his second wife, Mary, who remarried after her husband’s death and relocated to Edinburgh. The Land Tax suggests that four new modestly-sized houses were built on Goulston Street or Square in the 1760s followed by sixteen in the early 1770s. The freehold claim to the Goulston estate was passed on to his widow who sold it at auction in 1776 to John Burnell, likely instigator of a final Goulston Street extension.3

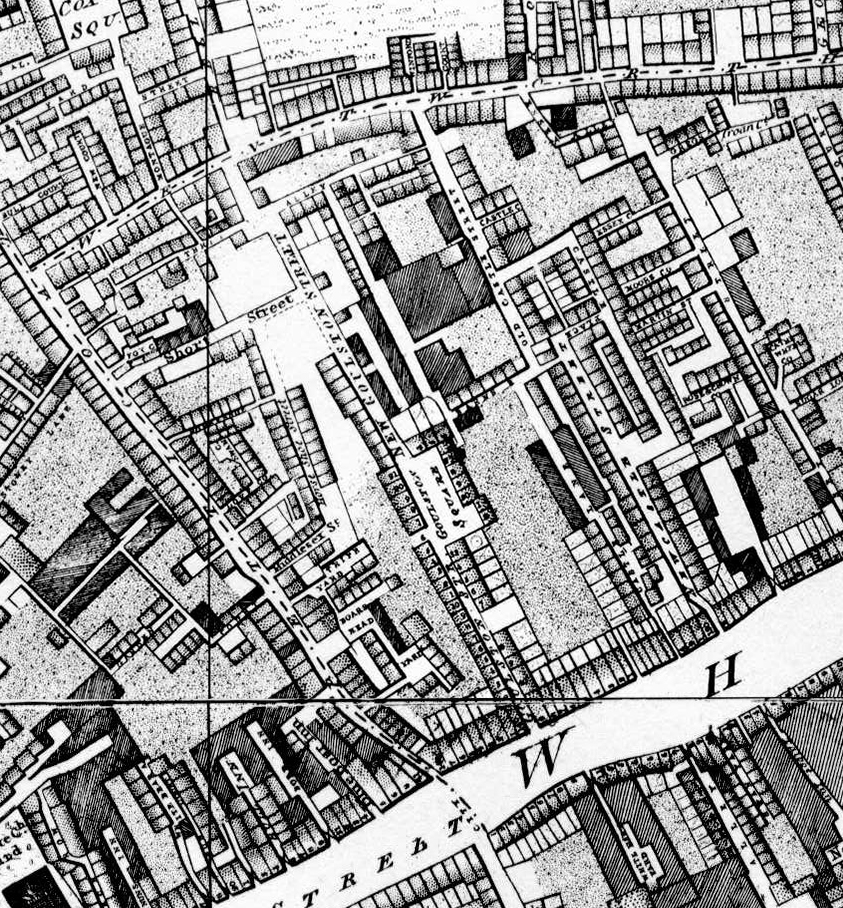

Horwood's map, 1792-3

This significant intervention was planned in the closing years of the eighteenth century and by 1813 an extension to Goulston Street punctured the north-western edge of Goulston Square, necessitating the demolition of two houses in order to create a road that linked Whitechapel High Street all the way through to Wentworth Street. This new line of building took advantage of uninhabited land to the north of the square which was intriguingly identified as ‘Blackguards’ gambling ground’ on Horwood’s first edition London map of 1792/3. Relatively narrow, irregular and latterly eroded by rebuildings, over time Goulston Square deferred to Goulston Street and, around the mid- nineteenth century, Goulston Street and Square were renumbered to reflect a new coherence within its northern arm. Whereas numbers formerly ran continuously in a clockwise direction from south-east to south-west around the street and square and excluded the new extension (which was in fact originally named New Goulston Street), the new system regarded Goulston Street as spanning from Whitechapel High Street right through to Wentworth Street, odd numbers on the west and even on the east.4

Horwood's map, 1813

-

Goulston (Gulston), Sir William, The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1660-1690, ed. B. D. Henning, 1983 [Online: http://www.historyofp arliamentonline.org/volume/1660-1690/member/goulston-(gulston)-sir- william-1641-87]; TNA, PROB 11/356/609 ↩

-

J. Coulter, Squares of London, 2016, p.521; LMA, MDR/1736/005/253; 'Roger Whitley's Diary: April 1684', Roger Whitley's Diary 1684-1697 Bodleian Library, Ms Eng Hist C 711, ed. M. Stevens and H. Lewington, 2004 [Online: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/roger-whitley- diary/1684-97/april-1684]; LMA, MDR/1726/003/299; D. Keene, P. Earle, C. Spence and J. Barnes, 'Middlesex, St Mary Whitechapel, Gulston's Square', Four Shillings in the Pound Aid 1693/4: the City of London, the City of Westminster, Middlesex, 1992 [Online: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/no- series/london-4s-pound/1693-4/middlesex-gulstons-square]; LPL, MS 2750/66; Land Tax: Caroline Stanford, ‘Revisiting the Origins of Coade Stone’, Georgian Group Journal, vol.24, 2016, pp.95–116 (101) ↩

-

Houses of Parliament, HL/PO/JO/10/6/102/2266, f.87–90, f.91-92; TNA, C 7/572/46, C 9/447/153, C 9/447/154, C 8/452/41, C 8/467/63, C 8/467/74, C 9/460/1, C 9/469/69, C 11/1463/20, C 11/1456/30, C 11/1852/19, C 11/1394/36, C 11/1581/14, C 11/1490/13, C 11/333/26, C 24/1247, C 24/1252; LMA, MDR/1724/006/0266, MDR/1724/002/0131, MDR/1726/001/0107, MDR/1726/001/0108, MDR/1730/004/0400, MDR/1731/002/0119, MDR/1736/005/0253, MDR/1736/005/0252, MDR/1737/004/0324, MDR/1739/005/0439, MDR/1740/004/0609; THLHLA, L/SMW/D/6/1 ↩

-

J. Coulter, Squares of London, 2016, p.521; MBW, 17 Aug 1860, pp.620-1 ↩

St Paul’s German Reformed Church

Contributed by Survey of London on Feb. 14, 2017

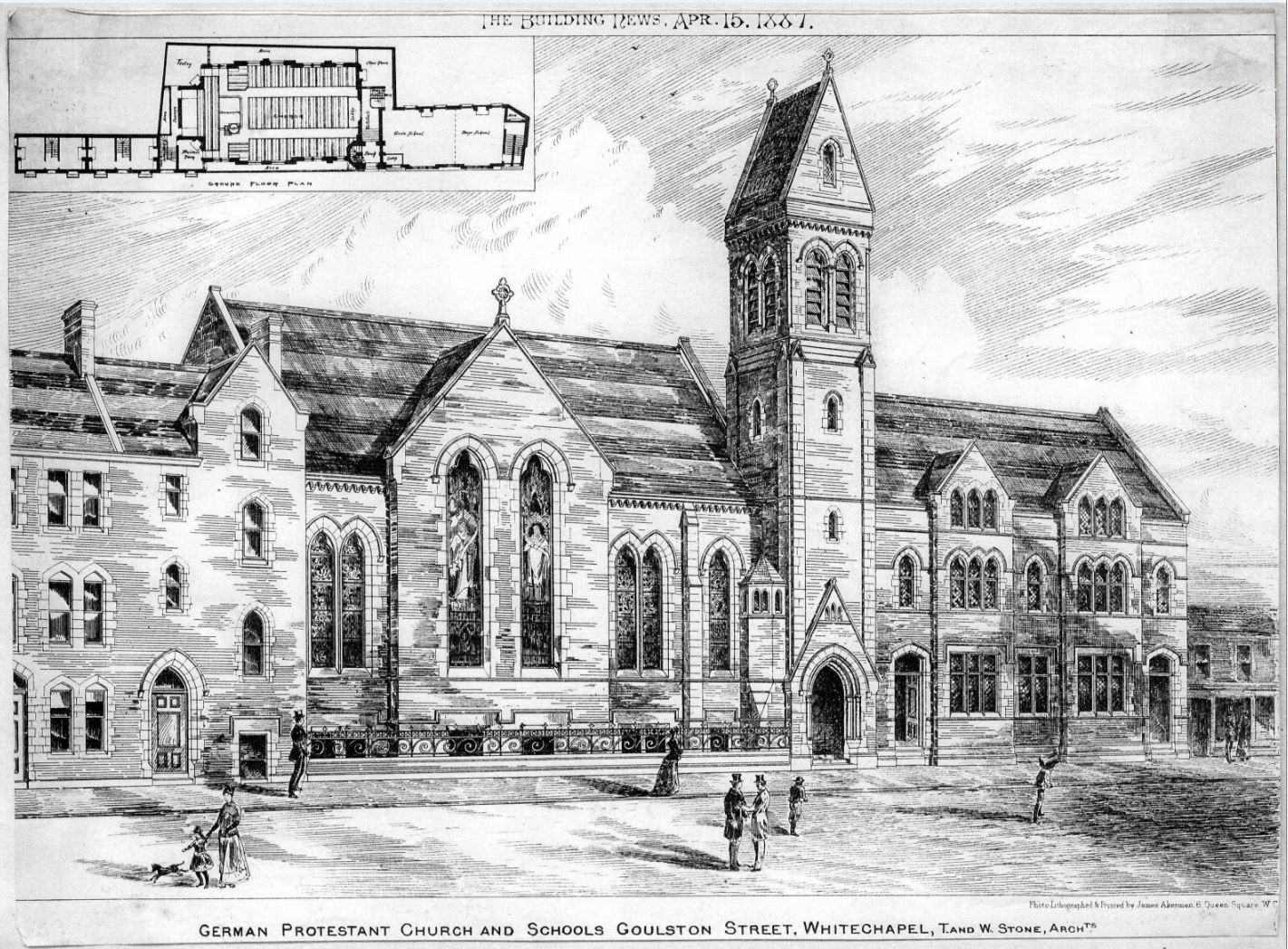

Founded in 1697, St Paul’s Reformed Church was London’s third oldest German evangelical congregation. In 1771 the church removed from its original home in the Savoy Palace to a purpose built building in Duchy Lane. Yet little more than forty years later the church building was abandoned to make way for the development of the new Waterloo Bridge across the Thames. This was the first of two compulsory purchase orders that precipitated the relocation of the church on two separate occasions in order to meet the city’s growing infrastructural needs. Looking east, the church council favoured a site in the thick of Whitechapel’s Deutsche Kolonie for a new building. A vacant plot at Hooper Square, Whitechapel, was acquired in 1818 and a year later the church was completed and consecrated. Further additions of a boys’ school in 1834 and a girls’ school in 1852 were made, followed by an “imposing” rebuilding of both schools in the 1870.1

This active congregation was again uprooted in 1878 when their Hooper Square building blocked plans for a large-scale railway depot for the London Tilbury & Southend Railway. This transportation hub was to occupy much of present- day Goodman’s Fields and the Hooper Square church was to be replaced by an engine house. Undeterred by this second upheaval, by 1885 St Paul's had settled on rebuilding for the third time and selected a new site further north in Goulston Street. The land had been previously held by Henry Clarke, tobacco manufacturer, and used as a jam factory before it was acquired and cleared by the Metropolitan Board of Works in their “grandest and costliest slum clearance scheme”. The church council secured £14000 in Chancery to fund the relocation and a sum of £6750 was used for purchase, leaving £7250 to support design and construction costs. Designed by architect brothers, Thomas and William Stone, the foundation stone of the new church was laid on 2 July 1886 by Baron J. H. W. Schroeder, an Anglo-German merchant of noble Prussian origin. Building work was undertaken by W. Gregar of Stratford at a cost of £9930 and completed by January 1887. During the period of rebuilding, services were held in the schoolroom of nearby St Mary Matfelon.2

Site plan of St Paul’s on

Goulston Street from Goad map of 1890

Site plan of St Paul’s on

Goulston Street from Goad map of 1890

St Paul’s at Goulston Street was one of the Stone brothers’ most prominent commissions. The practice also completed several other Primitive Methodist chapels in London, along with bank buildings in Hammersmith and Putney. Apprenticed to Charles Hambridge for nine years before setting up practice with his brother in 1862, Thomas (1836-1893), the elder brother, was admitted as a fellow of the RIBA in 1892. Of their design for St Paul’s, the Building News noted that the purchased land, left-over from the recent improvement scheme, was “rather irregular in plan, of which the greatest advantage has been taken”. The solid Neo-Gothic building comprised three blocks spanning 200ft north to south along Goulston Street and was principally constructed of yellow stock brick and Bath stone. The main church building was centrally located along this stretch, sandwiched between a substantially narrower school wing to the south and residential wing to the north. Divided from the school to the south by an entry porch and sober bell-tower, the elevated ground-floor chapel seated 350 and a lecture hall beneath held 500. A light-well ran along both eastern and western edges of the chapel block to serve a range of further subsidiary accommodation in the basement, maximising the circulation and lighting opportunities of the constricted site. This strategy also allowed for two parallel rows of stained-glass windows to illuminate the main gathering space which was orientated towards a northern altar and preaching pulpit. The timber chapel ceiling took the form of a semi-dodecagon and pews were of pitch-pine. The Building News held the organ in especially high esteem and deemed it a “most complete instrument” in spite of its reported compactness. Occupying the upper two floors of the school block were the minister’s and caretaker’s rooms as well as a dispensary and rooms dedicated to the ‘London Society for Promoting Christianity amongst the Jews’, a legacy of outreach work begun at Hooper Square. To the north two four-storey houses were constructed to let, to help pay off the ambitious building scheme.3

After the great exertion expended in the realisation of this substantial building project, a sharp decline in the fortunes of Whitechapel’s sugarhouses in the 1880s and a concurrent influx of East European Jews into the area resulted in an increasing dispersal of the German congregation throughout the city. In 1896 the church council was forced to close the school and let the associated rooms, limiting the extent of their educational activities to Saturday evening classes for children. Against the odds however, the church experienced a renaissance in the early twentieth century under a new pastor, Heinrich Deicke. Large attendances on Sundays, a new children’s service and an expanding women’s group were evidence of what was to be a mournfully short revival at St Paul's between 1905-1913. In 1914, newly appointed Pastor Loeffler was compelled to flee back to Germany having only taken up office one year earlier, his term cut short by the outbreak of war. Although violent attacks on German East Londoners were not infrequent during the difficult war years, St Pauls’ location may have protected churchgoers somewhat from the public gaze. Mrs John Streitberger (1868-1962), a member of the congregation during both the Hooper Square and Goulston Street iterations of the church, recalled of the First World War that "our church being in Aldgate most people took it to be a Jewish Institution so we were not molested and able to carry on". After Loeffler’s departure in 1914, St Paul's was overseen by the determined pastor of nearby St George's German Lutheran Church, Georg Maetzold, who remained active in his London ministry until 1917 when he too was forced to leave the country. Many in the congregation continued to meet, steadfast under extreme pressure, leading church treasurer of the time, J. Sandrock, to reflect that: 'Deep despair should have overtaken us on account of all the troubles and misery, but, as serious Christians we have accepted these great trials and shall endure them with patience…Earthly goods, money, possessions and honour have gone; our trust in God and the love of the Almighty cannot be taken from us. Our St Paul's congregation and our church is our fortress.' Although leaderless and depleted in numbers due to frequent emigrations back to Germany, both St Paul’s and St George’s limped on until Maetzold’s return in 1920.4

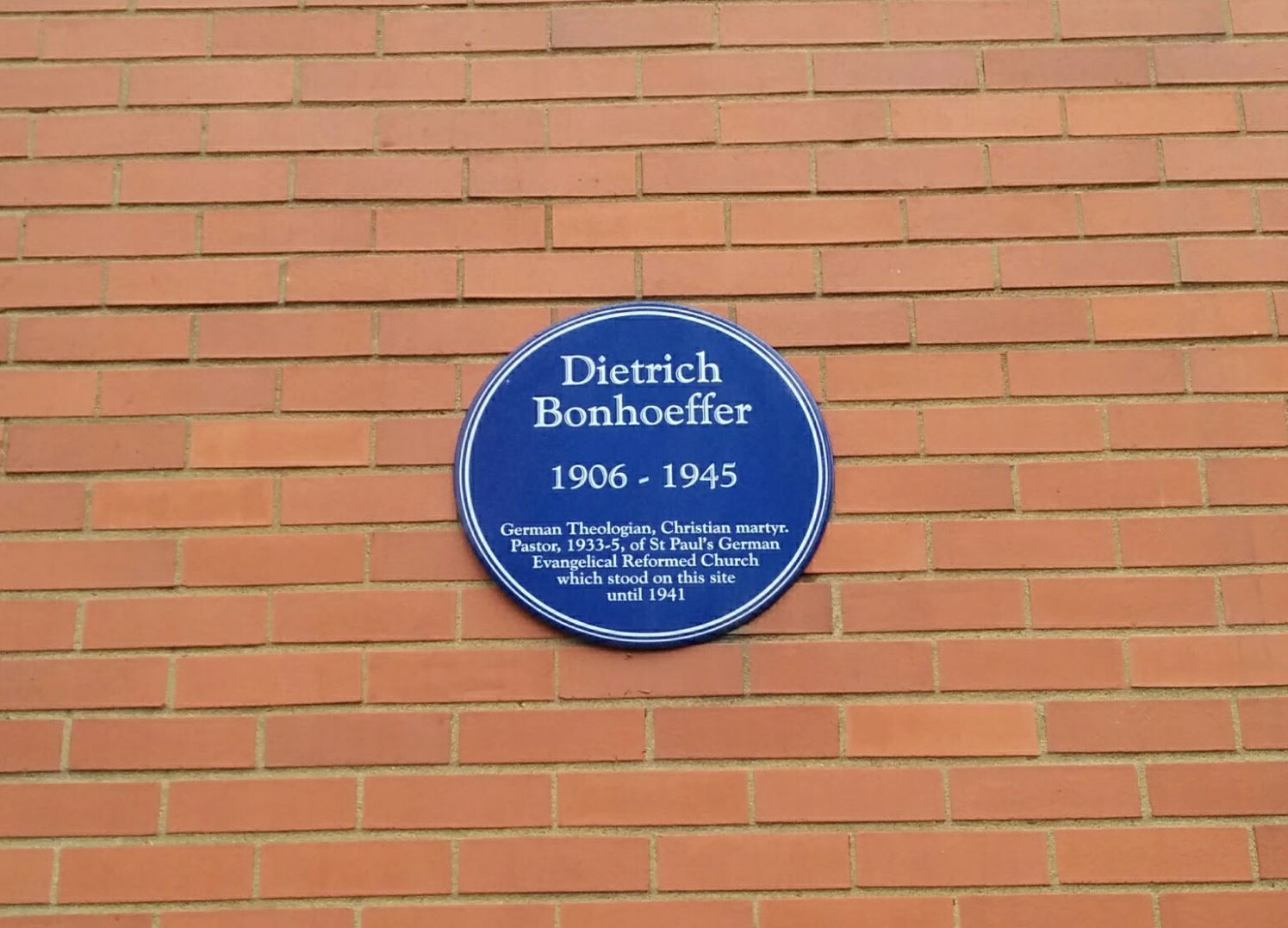

Maetzold continued to oversee St Paul’s until 1925 when a new pastor was installed in a spirit of optimism. The appointment was however shared with the German Evangelical Church in Sydenham, reflecting a loosening of ties between the German community and east London, the Kolonie now gone. Beginning in 1933, Dietrich Bonhoeffer notably led both churches in this combined pastorate whilst he formulated a new response to the Nazism infecting his beloved protestant church in Germany. He returned to his homeland two years later to engage in more direct resistance ministries. Meanwhile his successor at St Paul’s, Pastor Martin Boeckheler, reported that although the congregation was still reduced in size as a result of war and the stricter immigration laws that followed, the women’s ministry was still very active and a particularly charismatic music director oversaw a vibrant choir involving Germans and non- Germans alike. In 1936, to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the Goulston Street building, the church invested in a renovation of its fine organ. At this time, one service in every four was preached in English.5

Having survived the traumas of the First World War and three relocations, St Paul’s was bombed to ruins during an incendiary raid in January 1941. The popular music director, Eric Seymour, returned to observe that the organ and piano were in an unredeemable state and the rest of the building stood as “one huge mess of charred debris”. It was also reported that the 300 year old communion plate was stolen. Still, a heartbroken Seymour was hopeful, writing to a chorister in 1941: “Well! If we survive, we must have a ‘whip-round’ and build a new more modern church.” This time however there was to be no rebuilding and services were never restarted. In the succeeding decades, a remnant of the congregation gathered sporadically in the capacity of a trust charged with the management of associated church assets. At one of these sociable meetings in 1982, the re-establishment of St Paul’s German Reformed Church in the East End was again mooted in spite of the near complete loss of its German population. Nothing came of the idea and Whitechapel itself was deemed “most insalubrious and even dangerous” in any case.6

The only remaining evidence of St Pauls’ occupation of Goulston Street is a plaque unveiled in 2009 devoted to the memory of its most well-known pastor and theologian, Dietrich Bonhoeffer. After his return to Germany in 1935, such active opposition to Hitler ultimately cost him his life. Bonhoeffer was executed at Flossenbürg Concentration Camp in April 1945. Close to the vanished pulpit where he preached many sermons, his vocal resistance to fascist agendas is rightly remembered.7

-

LMA, ACC/1767/001 ↩

-

LMA, ACC/1767/003, ACC 1767/005, ACC 1767/008; MBW, 11 Jan 1884, p.752; Jerry White, Rothschild Buildings: Life in an East-End Tenement Block 1887–1920, Chapter 1; Pall Mall Gazette, 4 July 1885, p.8; Daily Express, 13 June 1888, p.8; The Building News, 15 April 1887, p.554; The Builder, 3 April 1886, p.530; The Builder, 3 April 1886, p.530 ↩

-

RIBA Nomination Papers fiche ref: 112/G1; RIBA Proceedings NS, v9, 1893, p.375_; Dictionary of British Architects 1834-1900_, Vol 2, p.880; The Building News, 15 April 1887, p.554; DSRs ↩

-

LMA, ACC 1767/005, ACC 1767/008; Der Londoner Bote, Sept. 1962, pp.5-15 ↩

-

LMA, ACC/1767/004, ACC 1767/005, ACC/1767/009 ↩

-

LMA, ACC 1767/005, ACC 1767/007; Daily Herald, 24 March 1941, p.5; ↩

-

‘German Churches’, St George-in-the-East Church website [Online: http://www.stgitehistory.org.uk/media/germanchurches.html] ↩

Bonhoeffer Plaque, 2009

Contributed by Sigrid on March 8, 2017

The production of the Bonhoeffer plaque hanging near to where one of his London churches (St Paul's German Reformed Church) stood came about through the initiative of the Historic Chapels Trust and the Friends of St George's German Lutheran Church and was financed by the St Paul's German Evangelical Reformed Church Trust, the Friends of St George’s German Lutheran Church with the support of the London Metropolitan University, who own the building that the plaque is hanging on. The plaque was unveiled on Monday November 9, 2009 by the Rt. Rev and Rt Hon Richard Chartres Bishop of London and Vice Patron of the London Metropolitan University.

London Metropolitan University's Buildings

Contributed by Survey of London on Aug. 2, 2019

All the buildings between Goulston Street and Old Castle Street south of Arcadia Court and Herbert House, as well as one building on the east side of Old Castle Street, are occupied by London Metropolitan University (LMU). That institution was created in 2002 through the merger of the University of North London and London Guildhall University. Several of the buildings had since the early 1970s been occupied by one of the last’s predecessors, the City of London Polytechnic. These buildings, of the 1900s to the 1960s, were originally offices, warehousing and packing facilities for the Brooke Bond tea company. From the 1990s university use spread north to the site of the Goulston Square Baths.

Brooke Bond and Calcutta House

The dominant building on the LMU site is Calcutta House, the core of which is a packing factory built in two stages in 1910 and 1913–14 for Brooke Bond Ltd, tea dealers and blenders. This firm had been founded in 1869 by Arthur Brooke (1845–1918), a retailer of tea and coffee in Manchester, who within two year had five shops in Manchester, Leeds and Liverpool and had moved into wholesaling, which soon came to dominate the business. In 1873 Brooke Bond opened London premises at 58 Cheapside and 129 Whitechapel High Street, expanding greatly in the following decade, and offering a profit-sharing scheme to its 154 employees by 1882.1

The High Street property included stores to the rear that acquired a frontage when Old Castle Street was widened. Brooke Bond acquired other sites cleared in the road widening and from 1888 to 1895 built and rebuilt (following a fire) warehousing at 3–9 Old Castle Street. This may have been to the designs of the architect William Dunk; the buildings resembled his surviving warehouse at 31 West Tenter Street.2

Further northwards expansion followed from 1909, with the acquisition of the site south of the public baths that had been David King & Son’s builders’ yard. The architects of the first and northern part of the large steel-framed packing factory built here in 1910 were Sidney Stott Oldham in conjunction with Dunk, the builders G. Parker & Sons of Peckham. With five storeys over a basement, the former factory is red-brick faced to Goulston Street where the set-back building line of Goulston Square was maintained, the recessed southern bays leaving space for loading. Stone dressings include a bold arch-headed door-hood and narrow round-headed high-level staircase windows with keystones. Elsewhere vast rectangular windows light the former packing floors, and there is stock brick to the plainer Old Castle Street elevation. The broader southward extension of 1913–14, designed by Dunk & Bousfield and similarly constructed, was separated from the original building by a light well (covered by a steel bomb-proof cover in 1915). The packing floors extended into the former tenements that had been built with St Paul’s German church, emptied in 1914. There was thus an incongruously Gothic appendage to the warehouse’s Goulston Street front.3

Brooke Bond expanded yet further across Old Castle Street, taking the frontage opposite its complex, a shallow site that included the Green Man pub (see below) extending back only to Tyne Street. This was redeveloped in 1931–2 initially as a warehouse but converted during construction to be a staff welfare centre. Designed in a tentatively Expressionist manner by Albert Leigh Abbott (1890–1952), it was erected by local builders Walter Gladding & Co. Ltd. It is a four-storey and basement steel-framed building faced in brick and patent stone, with large steel-framed windows by Crittall Ltd. Entrances at either end lead to staircases and a lift was placed at the north end. An enclosed footbridge has always connected what was the top-floor directors’ dining room floor to Brooke Bond’s main building opposite. The ground floor included a workers’ lounge and dance room with a sprung maple floor, the first floor the workers’ dining room, the second the office-staff dining room and kitchens. Well specified, with teak joinery throughout, the building was also technologically advanced – a radio-gramophone piped music to speakers in all the rooms.4

Brooke Bond’s buildings were seriously damaged in the Second World War, the 1890s warehouses at 3–9 Old Castle Street completely destroyed. In 1946 Abbott oversaw repairs and designed a temporary light-steel structure for 3–7 Old Castle Street. The former church tenements at the south end of Goulston Street were replaced with a plain four-storey range. The basement of the ruined church and a surviving part of its schools were also taken over.5

By 1949 J. Stanley Beard was Brooke Bond’s architect. He designed the warehouse and packing building that went up at 7–9 Old Castle Street in 1951, extended south to Nos 3–5 in 1955. This was to house paper stores, tea packers, tea-chest repairs and engineers, and incorporated a large loading bay. It is in the Utility style typical of much 1950s rebuilding locally, faced in red brick with steel strip-windows in thin concrete frames. Beard, who designed Brooke Bond’s blending factory in Bristol in 1959, designed further three- and four-storey warehouses for the south end of Goulston Street’s east side in 1961. Built in 1964–5, these were for paper stores and a sales department above loading bays to the north and a maintenance office and stores to the south.6

In 1968, after a century of expansion tied up with the British Empire, especially north-east India, Brooke Bond merged with another multi-national food producer, Liebig, inventors of the Oxo cube. Its Whitechapel buildings were soon given up.7The City of London Polytechnic was formed in 1971 as a result of policies given impetus by the publication in 1966 of a White Paper, A Plan for Polytechnics and Other Colleges. The science and technology departments of Sir John Cass College (whose art department already had a Whitechapel presence in Central House) amalgamated with the business-focused City of London College. The former Brooke Bond buildings were taken over in 1972 and in 1974 adapted to reflect the science focus and integrated as Calcutta House by Fitzroy Robinson and Partners, architects. Basements included specialist labs (microbiology, neurophysiology, ‘toxic procedures’), and the 1950s building on Old Castle Street had an ‘animal room’, with fish tanks, birds and mammals. Upper floors had lecture rooms, offices, a refectory and lounge. The former welfare centre on Old Castle Street was given a language lab in the basement and a library on the first floor.8

The Women’s Library and later developments

In 1992, the City of London Polytechnic was granted university status as London Guildhall University. A year later it acquired the derelict former public baths to the north of its existing premises with permission for change of use and a view to expansion for library, computing and exhibition space, conference facilities and office and teaching areas. The University hoped finally to find suitable accommodation for the Fawcett Library, acquired in the 1970s from the Fawcett Society, which had its origins in the London Society for Women’s Suffrage, and housed unsuitably in the basement of Calcutta House. An outline scheme of 1995, in a feasibility study by Jones Lang Wootton, proposed redevelopment on the L-shaped footprint of the baths, with a typical early-1990s feature, a corner octagon, on Goulston Street. The Fawcett Library would be set back from Old Castle Street behind a ‘suffragette garden’. Only the east or Model Baths side of the site was developed initially, following a competition won in 1995 by Wright and Wright Architects. Construction in 1999–2001 with Kier as main contractors cost £4.4 million, funds coming from private and public donors, the Heritage Lottery Fund being the most significant.9

The client’s brief requested the new library ‘feel permanent’. Wright and Wright’s design made use of thick concrete walls which contributed to a restrained architectural aesthetic while improving environmental performance. As in Baly’s Model Baths, design was technology-led, ornamentation shunned in favour of efficiency and ventilation. Yet, in a notably if not uniquely intelligent instance of façadism, the practice elected to retain the Old Castle Street front wall of 1846, a gesture to a kind of continuity as thousands of women had come through here. The building behind occupied only about three quarters of the plot’s width, space to the north given up to be a paved garden with silver birches behind the stepping down north wall of the baths. In its dignity and pragmatism, the building was regarded by the architectural press as a ‘model of politeness’. Indeed, it was the willingness to engage with the site’s history that Claire Wright believed won the architects the commission. Behind the punctuated black-painted façade, a substantial red-brick block steps back, rising to five storeys above a basement. Internally, accommodation was arranged around a central ground-floor exhibition space within which there was a pod-like double-height seminar room. A modest staircase led to a first-floor café lit by the arch-headed windows of the 1840s façade. Upper floors housed the archive, reading rooms and a double- height library across the front of the building with a shallow barrel-vaulted ceiling. Connections between these diverse and interlocking spaces led The Architectural Review to laud the building for possessing ‘the elegant complexity of a Chinese puzzle’. It has been argued that the rejection of conventional spatial hierarchies was a self-consciously feminist act. In 2002 the Women’s Library was awarded the RIBA Journal’s ‘Best UK Building of the Year’ Award.10

London Guildhall University gained backing from the Higher Education Funding Council for England for redevelopment of the Goulston Street side of the former baths site in 1999, but works had not begun in 2002 when it merged with the University of North London, another former polytechnic, based in Holloway Road. This was the first merger of two universities, and the new London Metropolitan University was in its student numbers the largest university in the UK. The Goulston Building, as it became, went up in 2003–4 as a law and business school. Also designed by Wright & Wright, it was built by Willmott Dixon, contractors. The long and undemonstrative range echoes the red-brick elevations and strip windows of Calcutta House’s post-war buildings. There is a recessed entrance at the four-storey south end giving access to a long double-height top-lit corridor that is a common room and exhibition space. Teaching rooms originally included one configured as a mock courtroom. The building also incorporates barrow storage for Petticoat Lane market at its north end. The former warehouse of 1964–5 at the south end of Goulston Street had its loading bays infilled with glazing in 2004 to the designs of Robert Hutson architects, to create another double-height reception area, this building being otherwise devoted to library and study space.11

The Women’s Library lasted only until 2012. London Metropolitan University, hit by funding crises including a ban on international students, could no longer afford to run it and the collection was sold to the London School of Economics. In efforts reminiscent of those to save the baths on the same site, the ‘Save The Women’s Library’ campaign gathered a petition with over 12,000 signatures and the backing of prominent supporters including RIBA President Angela Brady. One protester reflected that the Library and its award-winning home belonged together, like ‘a body and its insides’, but to no avail. In 2015 Molyneux Kerr Architects altered the interior by replacing the seminar- room pod with a lecture theatre. The University’s own archival collections were brought to the site, along with the Trades Union Congress Library, the Archive of the Irish in Britain, and the Frederick Parker Collection, over 200 chairs and archives relating to the history of British furniture-making.12

Following the sale of Central House in 2015, the Cass School of Art was relocated to Calcutta House in 2017 on a temporary basis pending the intended consolidation of London Metropolitan University on a single site at Holloway Road, the size of the student body being much reduced following the ban on overseas students. ArchitecturePLB and Willmott Dixon Interiors oversaw the adjustments. The Architecture Department moved to the Goulston Building, law departing for Moorgate, and the former staff-welfare building on the east side of Old Castle Street was refurbished to create workshops and studios.

Other studios and related space in Calcutta House were intended ‘for a design life of only two years’, but in 2019, as growth returned, it was announced that LMU had scrapped its ‘one campus, one community’ plan and that the Cass would remain at Calcutta House.13

-

Leeds Mercury, 10 Oct 1871, p.1: Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 7 April 1870, p.7: Manchester Evening News, 23 May 1873, p.1: Royal Commission on Labour: Appendix to the Minutes of Evidence, 1894, p.207: Post Office Directories: David F. Schloss, Methods of Industrial Remuneration, 1892, pp.173–4: Report on Profit Sharing and Labour Co- partnership, 1920, p. 150 ↩

-

London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), GLC/AR/BR/06/034933/001–2; District Surveyors Returns (DSR): Getty Images: Mansfield Reporter, 21 July 1893, p.2 ↩

-

DSR: LMA, GLC/AR/BR/06/034933/001–2: Historic England Archives (HEA), Aerofilms EPW005770; EPW055309 ↩

-

DSR: LMA, GLC/AR/BR/053188/001: Ancestry: The Builder, 28 Oct 1932, pp.722,729–30 ↩

-

LMA, GLC/AR/BR/06/034933/001–2; GLC/AR/BR/13/053188/01: HEA, Aerofilms EPW011143: Tower Hamlets planning applications onlin (THP) ↩

-

THP: LMA, GLC/AR/BR/13/053188/01; GLC/AR/BR/06/034933/001–2: Official Architecture and Planning, vol.22/10, Oct 1959, back cover ↩

-

LMA, GLC/AR/BR/13/053188/02] ↩

-

LMA, GLC/AR/BR/13/053188/001–2: THP ↩

-

London Metropolitan University (LMU) Archives, TWL000000049; TWL000000243; TWL000000247–8: THP: Annmarie Adams, ‘Architecture for feminism?: The Design of the Women’s Library, London’, Atlantis: Critical Studies in Gender, Culture & Social Justice, vol.29/1, Fall/Winter 2004, pp.99–105 (p.100) ↩

-

LMU Archives, 727.309.4215 GOU; TWL000000246; TWL000000247: The Fawcett Library Annual Report, 1st August 1997 to 31st July 1998, 1998: Architects' Journal, 23 Feb 2006, p.26: Adams, p.100: Catherine Slessor, ‘Making History’, Architectural Review, vol.211, Jan 2002, pp.50–7 ↩

-

LMU Archives, 727.309.4215 GOU; 3701022156: Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives, Building Control file 18324: THP ↩

-

THP: savethewomenslibrary.blogspot.co.uk/ [accessed 6 July 2016]: www.thepetitionsite.com/925/128/986/save-the-womens-library-at-london- metropolitan-university/, [accessed 6 July 2016]: Daily Telegraph, 8 Nov 2012; www.theguardian.com/books/2014/mar/10/womens-library-reopen-london- school-economics-lse: www.londonmet.ac.uk/contact-us /how-to-find-us/the-wash-houses/: www.furnituremakers.org.uk/frederick-parker- collection/: information kindly supplied by Peter Fisher and Catherine Phillpotts ↩

-

THP: www.willmottdixon.co.uk/projects/calcutta-house- phase-1-2: information kindly supplied by Dr Lesley Stevenson ↩

'Woodlands' marked on Ogilby and Morgan map of 1676

Contributed by Survey of London

The ruin of St Paul's German church in 1960, shortly before demolition

Contributed by Survey of London

Calcutta House Annexe in 2021

Contributed by Derek Kendall