Chicksand Street to Old Montague Street - early history

Contributed by Survey of London on March 30, 2017

The rectangle of Whitechapel parish that projects north of Old Montague Street

as far as Chicksand Street was part of the Halifax or Osborn estate along with

much of Mile End New Town to the north and east. In 1643 Edward Montague of

Boughton, Northants, and William Montague and Maurice Tresham, both of the

Middle Temple, bought this land from William Smith and others at the Middle

Temple. The holding passed to George Montague, who became second Baron Halifax

and first Earl of Halifax of the third creation, which title lapsed on the

death of his son George in 1771. His heir was a nephew, Sir George Osborn,

baronet, son of Sir Danvers Osborn of Chicksands Priory, Bedford. Much of the

Osborn property was sold in 1849 to redeem mortgages, much of the rest in the

twentieth century.

Most of the estate that lay in Whitechapel (twelve acres) was leased around

1643 by Leonard Gurle (_c._1621–1685) to make one of London’s earliest general

nursery gardens. Supplying fruit trees as well as ornamental plants, Gurle’s

‘great garden’ was London’s largest nursery in the 1660s and 70s, and

continued after Gurle became Charles II’s gardener at St James’s Palace in

1677. It included 299 asparagus beds, 11,600 plum, cherry and pear stocks and

127 mulberry trees. In 1719 it was still in the occupancy of a Martin Girle, a

son or grandson, though the twelve acres had been leased in 1717 to John Ward

and William Mason. By the 1670s Whitechapel's stretch of Brick Lane was

solidly built up with thirty-four houses, the largest with ten hearths

belonging to Leonard Gurle. Montague (later Manby) Court off the north side of

the west end of Mountague Street, close to where Frostic Place succeeded. The

Montague Street frontage had been largely built up by 1700. Mason’s Court

(later Osborn Place) was a good-quality development of _around _1720 at what

is now the west end of Chicksand Street. In Mason’s ‘Great Garden’ open ground

behind, John Wesley preached and was stoned by unreceptive locals in 1742. The

place was considered as a possible site for the London Hospital in 1749, but

rejected on account of the proximity of a white-lead house.

The Osborn property in Whitechapel that had remained open was humbly developed

in the first two decades of the nineteenth century. Chicksand Street was cut

through and an irregular array of humble ‘places’ (courts) popped up off its

south side and to the north of Finch Street (named after Heneage Finch, the

second wife of Sir George Osborn, and now Monthorpe Road), which stopped short

of Brick Lane where another tiny court, New Mason’s Court (later Hanover

Place), was built in the 1780s. What is now Spelman Street was laid out as

John Street, Casson Street as George Street (both renamed in 1883). Hope

Street linked Finch Street to what had by this time been dubbed Old Montague

Street.

The sites of 2–38 Brick Lane were occupied by 1680 by small houses, most

likely comparable to and contemporary with what was built to the west on the

Fossan Estate in Spitalfields in the late 1650s. Running east from the top

end, Mason’s Court, after William Mason, was a superior development of around

1720, eleven good-sized three-storey houses, many of them double fronted and

five bays wide. They became Osborn Place in the 1780s when (New) Mason’s Court

was formed to the south, about where Hopetown Street is now. Osborn Place was

again renamed as the west end of Chicksand Street in 1939. In its early days

as Mason’s Court a number of the occupants had French surnames, presumably of

Huguenot origin, and the silk industry was an important presence, spilling

over as growth out from Spitalfields. Along the north side, a weaver, Abraham

Fleury, had No. 2 by 1740, and Samuel Bradford and John Ireland, silk

dressers, were at No. 3 around 1790–1800. Among silk throwsters were James

Plantier then Peter Merzeau, who had No. 5, with a workshop, in succession

through the second half of the eighteenth century. At No. 2 in the 1820s was

William Ayres, a carpenter, his wife being a tambour maker. Poverty crept in.

At No. 3 Ellen Smiles, age 52 and recently widowed, living in a single room

with three children, her eldest Sarah, 18, working as a match-box maker, died

in 1864 of what was said, possibly inaccurately but nevertheless tellingly, to

be starvation. Two years later cholera deaths in the area were attributed to

overcrowding, particularly among Jewish immigrants, and in 1872 a house

further east in Chicksand Street was declared wholly unfit for habitation

after the death of a cellar-dweller.

Two of the Mason’s Court houses (originally Nos 6 and 7 at the east end of the

south side) survived into the 1960s as 8–12 Chicksand Street. These were for

many years the front premises of Robert Womersley & Son, drysalters

(dealers in chemical products). In 1797 Robert Womersley, a Yorkshire Quaker

and linen draper who had set up a dye house, took an Osborn lease of the

property to set up as a drysalter for dying and other purposes in what was

still then a textile district. From 1815 the family no longer lived at the

chemical factory, which had extended southwards to Finch Street by the 1850s.

In later years the works came to be wedged between a school and a hostel.

There were new warehouses in 1929 and 1938, but the firm moved away in the

1950s.

Chicksand Street and Finch Street were formed and humbly and irregularly built

up with small two-storey dwellings in the first years of the nineteenth

century. By 1812 they were linked (east to west) by George (Casson) Street,

Little Halifax (Tailworth) Street, John (Spelman) Street and three small

courts – Dowson’s Place, Luntley Place and Eele (later Ely) Place; Stephen

Eele was a mason based on the New Road who had a lease of two houses on the

south side of Osborn Place and who may thus have been responsible for Osborn

Court’s four small houses, Dowson and Luntley were other developers. In the

same period Hope Street was formed to connect Finch Street to Old Montague

Street. There was sugar refining on Finch Street by 1814, George Brienlech

setting up as a preparer of molasses and a cowkeeper. By the 1820s, there was

a diamond cutter on Luntley Place. Much of the land was alienated from the

Osborn Estate.

The principal later interventions were schools, first where Dowson’s Place and

Luntley Place had been, then replacing part of Osborn Place and Osborn Court.

Other nineteenth-century buildings, mostly two-storey dwellings, stood into

the 1970s. The Bell public house at 40 Brick Lane, returning on the north side

of Chicksand Street, had moved here from its more southerly site around 1785

to make way for the road improvement that created Osborn Street. It was

rebuilt in its present form in 1873 for Barclay Perkins & Co. The pub

closed and from 1969 to 2013 the premises were Sweet & Spicy, opened as a

café by Ikram Butt, and of local renown in later years as a curry house.

Factory premises on the north side of Chicksand Street east of Osborn Place

were Francis George March Desanges’s silk-dying works from the late 1830s, a

successor to Sir Francis Desanges’s Wheler Street premises. By 1850 they had

been divided also to accommodate Henry Cox, a manufacturing chemist, and J. H.

Heckman, a skinner and furrier. East of these works, Abraham Davis built

Helena Terrace, four pairs of back-to-back tenements, in 1889–91.

As further south, this whole area became poorer and predominantly Jewish by

the 1890s. There were many tailors, also fur dressers and shoemakers. Booth’s

survey, coming here from Spitalfields, noted ‘how the height of the houses

gradually increases as Whitechapel is approached’, and the ‘tendency in Jewish

districts to increase the accommodation both extensively by occupying other

streets and intensively by building higher houses.’ As if on cue, in

1898–9 the east side of Frostic Place, said to be all brothels over shops, was

rebuilt by D. and M. Cohen as four-storey ‘model dwellings’ called Frostic

Mansions.

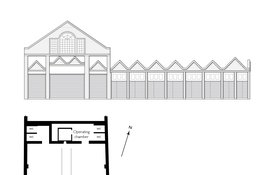

Abraham Davis put up an open-sided fish-market hall on the east side of Hope

Street in 1901–2, along with a row of eight lock-up stores to its south, all

with gable fronts. J. Leonard Williams was the architect. This was adapted for

occasional use as the ‘People’s Market Cinema’ in 1909–10. There was other

development by some among Davis’s brothers to the east on this block in the

same period. In 1927 the market was reappropriated to be a Poultry Shechita,

or kosher slaughtering yard, a business that dominated both sides of Hope

(from 1938 Monthorpe) Street into the post-war period, and drew curious

children as spectators. Further west there were miscellaneous factories behind

tenements on Finch Street. All this came to be subsumed in the Greater London

Council’s clearance plans of the 1960s.

Chicksand Street’s schools and Hopetown

Contributed by Survey of London on March 30, 2017

The westernmost section of what had been Francis George March Desanges’s silk-

dying works on the north side of Chicksand Street was adapted to be a ragged

school, said to be among several established through the reforming zeal of the

Rev. William Weldon Champneys, so perhaps in the 1850s, though it was not

listed in directories before 1868. The School Board for London accepted its

transfer from parish control in 1872, when it was said to be attended by 493

children. The block of houses across the road to the west of Luntley Place was

acquired and cleared and the ragged school replaced with Chicksand Street

School in 1877–8, for 528 children and of three storeys but not a triple-

decker, rather comparatively low, undemonstrative and without a hall. A second

parallel range was added to the west for an Infants’ Department for 480 more

children in 1886–7. Samuel Jerrard of Lewisham was the builder in both cases.

The former ragged school across the road was retained as a cookery (later

‘domestic economy’) centre. From 1905 Chicksand Street School was a ‘school

for special service’, that is one in a difficult neighbourhood at which

teachers were paid a bonus. The accommodation for infants was found wanting in

1911 and plans for eastwards expansion were advanced up to 1913, but not seen

through, presumably on account of war. The sharp decline in the roll that was

a consequence of the war led to the closure of what had long been thought an

unsatisfactory school in 1924.

Chicksand Street School fell into dereliction before being converted in 1931

to be Hopetown (or Hopetown House), a Salvation Army women’s hostel. The

project, first mooted in 1928, was overseen by Oswald Archer, the Salvation

Army’s architect. The hostel (or common lodging house) was a successor to the

Hanbury Street Shelter, founded in the early 1880s in a rented house by

Elizabeth Cottrill, a Whitechapel Salvationist, as the Army’s first rescue

home and women’s refuge. Very densely used, it came to be called Hope Town.

The new premises, opened by Queen Mary, had dormitory accommodation for 305

women. Finch Street was renamed Hopetown Street in 1939 and the hostel

continued here up to 1980, being demolished soon after to make way for GLC

housing in the shape of the Hopetown Estate. It was replaced on the south side

of Old Montague Street.

In 1905 the LCC decided to provide a special school in this locality for

children suffering from favus, a contagious skin disease. This was to be to

the west, separated from Chicksand Street School by Womersley’s chemical

works, fronting Osborn Place (demolishing most of the south side’s early

Georgian houses) and replacing Osborn Court. But there were delays with

acquisition of the site. The facility opened in temporary accommodation in

1906 and was soon designated Finch Street School, even though it faced Osborn

Place. Building work was undertaken in 1907–10 by J. Grover & Son, to

accommodate 60 ‘mentally ill’ and 60 ‘physically ill’ children up to the age

of 14 with two classrooms, a bathroom, a medical room for examination and

treatment, and a teacher’s room. However, before completion the number of

favus cases declined such that only three pupils were set to return after the

summer break in 1909, so the premises were adapted to be a cleansing centre

for children infected with vermin. Such children had been excluded from

schools until legislation in 1907–8 (the LCC General Powers Act 1907 and the

Children Act 1908) made cleansing stations possible; others were

simultaneously established in Finsbury, Bermondsey and the Strand. Nurses

washed children in a timber-built shed that stood south of the school on the

north side of Finch Street. Additional baths were acquired in 1913 and

1919–20, the last for the treatment of scabies in ‘Children’s Medicated

Baths’. Thereafter the designation as a cleansing centre or station was

changed to bathing centre.

Finch Street School and the former bathing centre were converted by the LCC in

the 1950s to be the Osborn Place Cookery Training Centre. The former bathing

centre was demolished in the 1960s, the school around 1980.