The Pavilion Theatre (demolished)

Contributed by Survey of London on Aug. 25, 2017

The site of 191-193 Whitechapel Road has been an empty frontage for more than

half a century, but it and the land behind occupy a place of importance in

London’s theatre history. The Pavilion Theatre, in business here for little

more than a century (1827 to 1934), was one of Whitechapel’s landmarks. Its

arrival was part of the general development of what had been garden ground

behind 181–193 Whitechapel Road in the mid 1820s.

The first theatre, a small playhouse, was built by John Farrell, said to have

been an actor, and William Hyatt (known as Wyatt) in 1826. It was open by

February 1827 and within the year was billed as the new Royal Pavilion

Theatre. Promoted as being on Whitechapel Road, it was in fact well back from

the road, immediately south of Caroline Place and behind houses on Baker’s

Row, the only point of access at first; it stood about where 15–25 Vallance

Road are now. At first unlicensed, and therefore liable to be closed down, the

future of the establishment was secured in 1828 thanks to the collapse of the

Royal Brunswick Theatre. That led to the transfer of both a license and

performers. A new lease was agreed and improvements were immediately planned,

including a long ‘avenue’ to the main road for patrons of the boxes. The

Baker’s Row entrance was kept for the gallery, with houses there used for

dressing rooms. George Chambers, known as an artist of ships and seascapes,

gained employment as a scenery painter here in late 1829. Nautical melodrama

was widely popular, and perhaps particularly emphasised here to establish the

succession from the Well Street theatres. Even so, respectability was sought,

suspected prostitutes being banned entrance. Farrell alone acquired leases of

the site of 193 Whitechapel Road and land behind in 1830. Buildings that

included the covered passage or ‘avenue’ were up by 1836. The street front was

a three-bay stuccoed classical edifice, of some grandeur in the local context

with a double order of paired Ionic columns, black on the ground floor and

fluted to a piano nobile. The lease was sold in 1839 and a series of sub-

tenancies followed.

Fire destroyed the empty theatre on 13 February 1856. The roof collapsed,

leaving the auditorium and stage a shell; the distant main-road frontage was

not affected. The lease had passed to Charles Conaughton, an Irish gas fitter

(according to the Census of 1851). He died in 1853 leaving his property to his

Whitechapel-born 21-year old daughter Elizabeth M. A. Munro, she having

married Donald Munro, a Scottish linen-draper on the Mile End Road. The

theatre, its machinery and wardrobe had been insured. That permitted Elizabeth

Munro to undertake rebuilding on a significantly larger scale in 1858,

agreeing a new head lease with the Bacon estate and subletting to John

Douglass, proprietor of the Great National Standard Theatre, Shoreditch, who

became the Pavilion’s manager and paid for the fitting up of the premises.

They opened as the ‘New Royal Pavilion Theatre’, claiming also to be ‘The

Great Nautical Theatre of the Metropolis’. First designs had been by Arthur

Taylor, architect, but his place was nominally taken by G. H. Simmonds; the

Builder reported that architectural duties were in several (un-named) hands.

The capacious auditorium could seat 1,750 to 2,000, and the gallery had room

for 1,200 to 1,400. However estimated, capacity was greater than at Covent

Garden’s new theatre. There was improved circulation and egress, though

inadequacies were sharply noted. From Whitechapel Road the ‘superb Parisian

avenue’ (10ft6in. wide and 172ft long) was an arcade of Portland stone and

corrugated iron off of which there was a refreshment saloon. The 70ft-wide

stage to the north had a great Corinthian proscenium arch. In the auditorium

slender columns and ring beams of cast iron supported the balconies. Internal

décor was of white and gold with crimson velvet for the box fronts and

curtains. The painted domical ceiling, seemingly unsupported, had a central

glass chandelier by Defries and Son.

An attempt in 1859–60 to attract more respectable audiences that included the

construction of private boxes and stalls and a renaming as the East London

Opera House appears to have met little success and in straitened times the

theatre failed in 1869. Munro tenure of the theatre property and its environs

was consolidated in 1861–2, extending to all the Baker’s Row properties

immediately to the east and nearly all those to the south on Whitechapel Road.

The widening of Baker’s Row in the early 1870s gave the Munros an opportunity

to acquire the southerly part of that frontage, which permitted minor

additions to the theatre in 1873, overseen by Jethro T. Robinson, architect,

and redevelopment along the street in 1873–6. Donald Munro became

Whitechapel’s representative on the MBW.

From 1871 the Pavilion’s proprietor had been Morris Abrahams under whom the

theatre cemented a reputation as a leading popular venue: ‘It is perhaps the

most cosmopolitan pit in the metropolis. Here may be seen the bluff British

tar; the swarthy foreign sailor fully arrayed in a picturesque sash, a red

mob-cap and a pair of ear-rings; the Semitic swell in glossy broadcloth and

the rorty coster, a perfect blaze of pearly buttons artistically arranged in

an elegant suit of corduroy with a natty bird’s-eye neckerchief tied in an

imperceptible knot; the sallow, callow youth in the shortest of jackets and

the largest of stand-up collars; the sallow youth’s sweetheart; the

respectable tradesman accompanied by his wife, five children and a large bag

of provisions and a bottle of enormous dimensions, a trio of artless maidens

who giggle and weep torrents.’ Extensive alterations were made in 1884

with John Hudson as architect, including to the street frontage and the

proscenium wall, to meet MBW stipulations arising from a general review of

theatres prompted by the destruction of the Ring Theatre in Vienna in

1881.

Further minor alterations to circulation and refreshment facilities on the

Baker’s Row side in 1889–90 were handled by S. Walker and Rüntz, surveyors.

Ernest Augustus Rüntz was the Munros’ son-in-law, having married Mary Ann

Munro in 1883. He was to establish a reputation as a theatre architect. With

Abrahams given a new lease under Mrs Munro, Rüntz was responsible for more

extensive reconstruction in 1894 under the eye and influence of C. J. Phipps.

This included an entirely new Doulton’s terracotta façade to Whitechapel Road,

widened to the east to permit separate entrances to the pit and stalls or

boxes. Rüntz gave the upper storeys increased presence with a double-height

recessed arch above a balcony. Around a large oculus, for advertising, there

was relief sculpture depicting Tragedy and Comedy, modelled by William J.

Neatby. The auditorium was raised, ceiled with figurative painted decoration

by Nepperschmidt & Hermann, and reseated with electric blue upholstering.

There were also lateral extensions of the stage with a taller fly tower in a

huge mansard spanning 64ft. Between the flies to the back was a scene-painting

workshop, and there were new dressing rooms and bars, in particular a roomier

refreshment saloon at circle level. Rüntz oversaw further reseating in 1906–8

to give a capacity of 1,832 of which 516 were standing and 500 in the gallery.

Now managed by Isaac Cohen, this vast home to melodrama and pantomime was ‘the

Drury Lane of the East’.

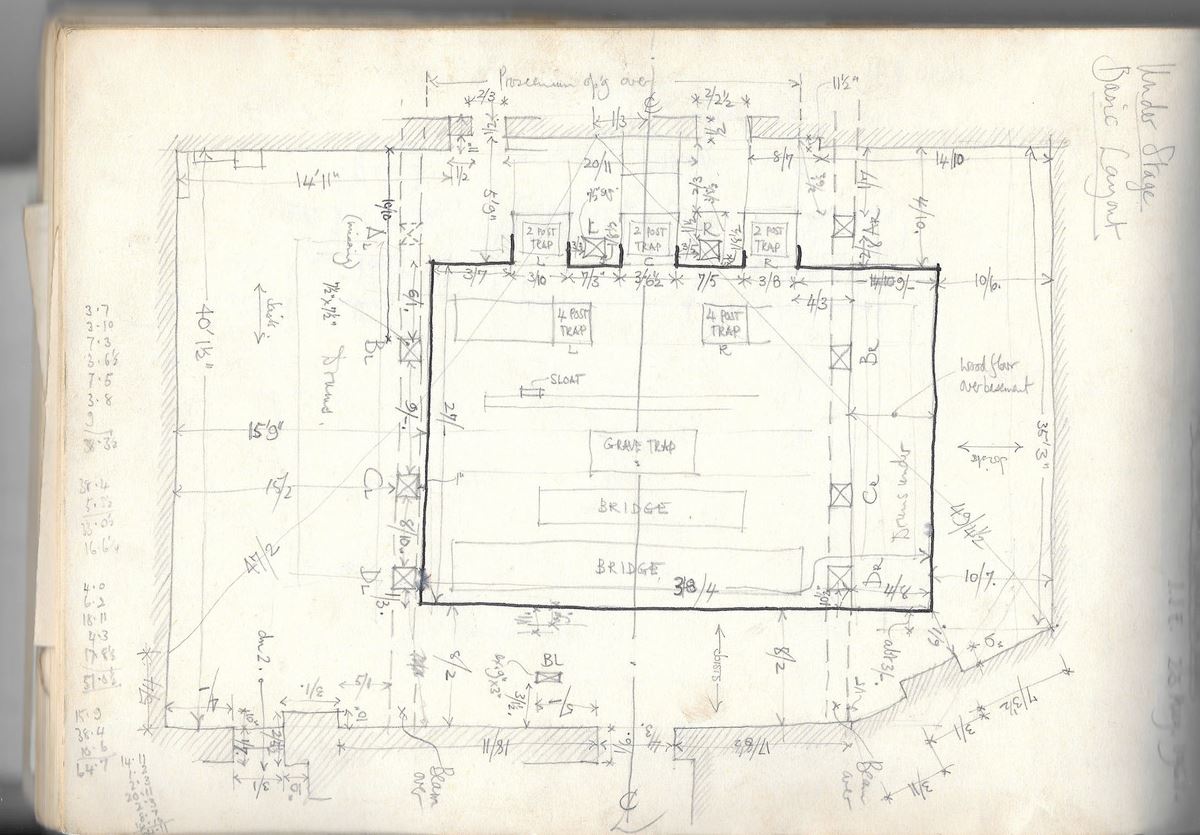

The Pavilion

Theatre, ground-level plan as in 1894 (drawing by Helen Jones)

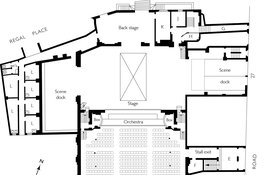

The Pavilion

Theatre, ground-level plan as in 1894 (drawing by Helen Jones)

After 1900 the Pavilion came to be known for the staging of Jewish plays, to

some extent through the short managerial stints of Max Merton and Laurence

Cowen, whose first play, The World, the Flesh and the Devil, premiered here

in 1909. In that year a meeting in support of the establishment of a Jewish

theatre in east London drew more than 2,000 to the Pavilion – ‘it was an

auditorium where everybody knew everybody else, and was not ashamed to say so,

in strident tones to be heard from gallery to stalls. The noise never

stopped.’ Management passed to Jacob Woolf Rosenthal, Polish-born, who

responded to financial problems in 1911 by proposing cinema use. The

Whitechapel Foundation, freeholder and neighbour, agreed to this, but resisted

proposals for opening on Sundays, the Jewish clientele notwithstanding.

Rosenthal moved away but came back in 1922 to stay until the end. Minor works

of alteration in 1922–3, with Herbert O. Ellis & W. Lee Clarke as

architects, were completed with a projecting illuminated sign at first-floor

level advertising ‘VILNA TROOP’, the international Modernist Yiddish theatre

company whose production here of Sholem Asch’s The God of Vengeance, set in

a brothel and with a favourable portrayal of a lesbian relationship, was shut

down by the censor. Rosenthal, always precarious, planned to sell up to Savoy

Cinemas Ltd, but this fell through in 1927 so he kept the Yiddish theatre

going. By now the superior lease was held by Sid Hyams, of a family of East

End Jewish cinema entrepreneurs. With George Coles as his architect, Hyams

proposed redevelopment on a larger scale for a theatre to take more than

5,000. But this failed to gain traction and cinema and occasional boxing use

continued alongside Yiddish theatre. The LCC stipulated extensive improvements

in 1932 to keep up with regulations. These were not carried out, forcing

closure in 1934 with Rosenthal clinging to the possibility of redevelopment.

The Hyams’s Gaumont Super Cinemas Ltd held out hope in the late 1930s, but the

transformation never came and after indirect bomb damage in 1940 the building

fell into dereliction.

The LCC acquired the property for clearance and housing development and in

1961 the theatre historian John Earl recorded the roofless ruins (see his

separate account). Clearance followed and an advertising hoarding occupied the

Whitechapel Road frontage from 1962 to 2012. Back land fell to use as a lorry

and car park and eventually into the ownership of Lidl. In 1988 Tim Reynolds’s

Academy Drama School unsuccessfully attempted unauthorised building work on

the site to form a theatre and classrooms. That property passed into the

ownership of Lidl and a scheme for a supermarket below flats that extended

east to Vallance Road was refused permission in 2013. The site remains empty

in 2020.

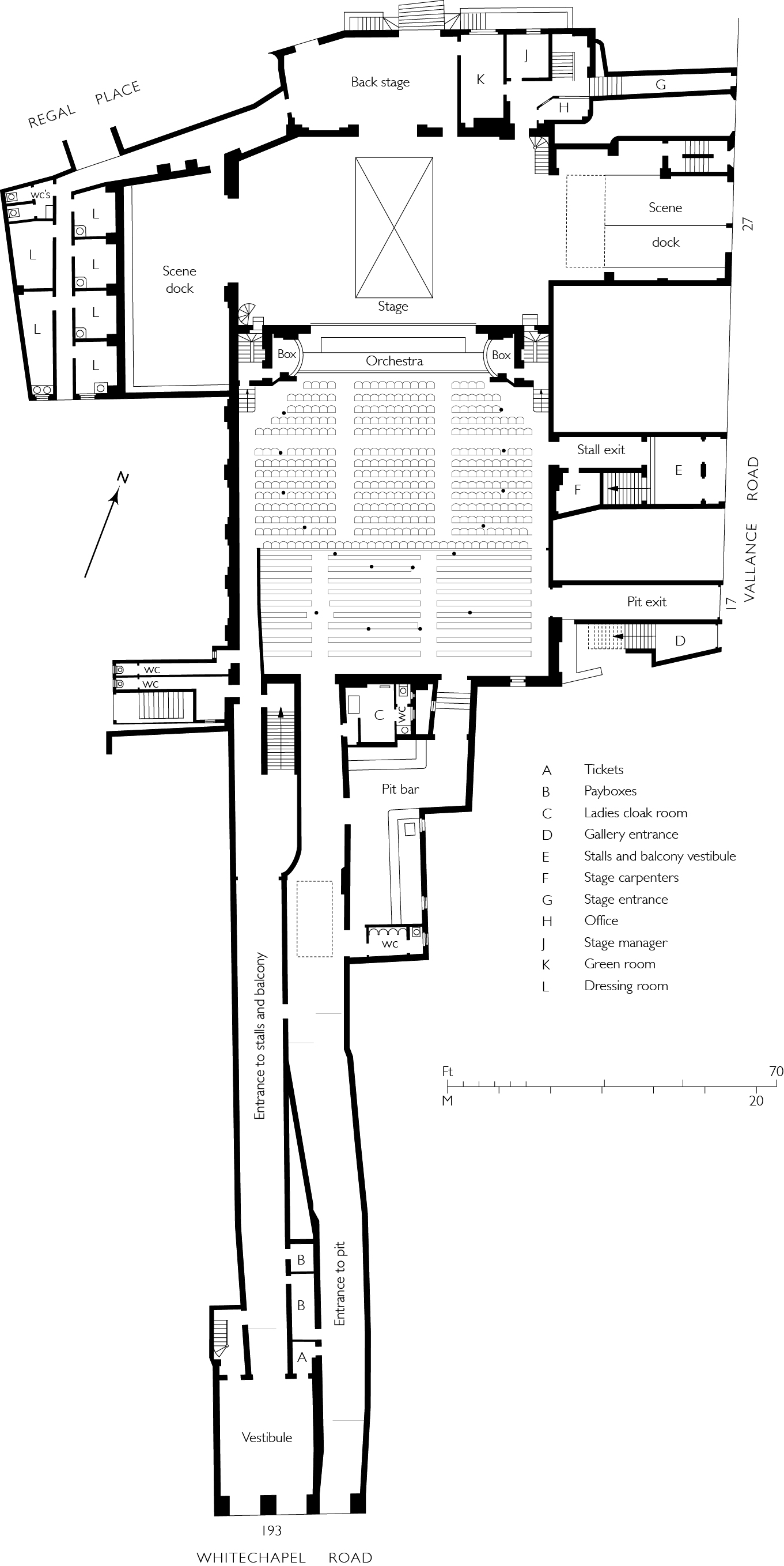

The Pavilion

Theatre, ground-level plan as in 1894 (drawing by Helen Jones)

The Pavilion

Theatre, ground-level plan as in 1894 (drawing by Helen Jones)