St Paul's School

1869-70, primary school, on the site of the Danish–Norwegian Churh of 1694–6

Danish–Norwegian Church

Contributed by Survey of London on Oct. 9, 2018

In 1692 King Christian V of Denmark and Norway and his envoy, Hans Heinrich von Ahlefeldt, grew concerned to counter schismatic tendencies among Danish and Norwegian Lutherans in London who had formed a congregation in Wapping. The community, in part maritime-mercantile and engaged in the rapidly expanding Scandinavian timber trade, in part mercenary soldiers hired by William III to fight in Ireland, had prominence through the presence in London of Christian V’s son George, who had married Princess (later Queen) Anne in 1683. Influence was deployed and agreements were reached. In 1693 Marine Square’s promoters, Nicholas Barbon and associates, granted a 999-year building lease to John Butcher, a Southwark timber merchant and carpenter–builder, who was acting as an intermediary and trustee for the Danish congregation. Butcher was given until 1696 to erect a church, to surround it with forty lime trees and to enclose the square, which was not to be used as a churchyard, burials to be kept to immediately beneath the church. John Parsons reserved the right to use the church for the Anglican liturgy. To him and his partners the church would no doubt have been a welcome addition to the then developing garden square, for its respectability and for the residential allure it would create for well-heeled expatriates.

Sir Thomas Trevor, Attorney-General, granted a warrant in April 1694 to Martin Lionfeld (also Morten Loynschar or Martin Lord Lyonfield) and Toger Wegersloff, Dano–Norwegian merchants resident in England, to erect the church in Marine Square for their compatriots. Other leaders of the merchant community, which had already raised £1,551, included Iver Brink, the congregation’s pastor who had been chaplain to the Danish forces in Ireland, Jonas Johnson and George Michelsen. The project was otherwise largely funded by King Christian V; he put forward upwards of £2,000 as well as an annual sum for maintenance. Lionfeld superintended the building project, which began immediately, the first stone being laid on 19 April 1694 by Mogens Skeel, Christian V’s representative, also known as a playwright. First designs, presumably arranged through Butcher, were by Thomas Woodstock, a carpenter who had worked at St Paul’s Cathedral, but who died that summer. In July Butcher’s lease was assigned to Lionfeld. Architectural supervision passed to Caius Gabriel Cibber, himself a Dane, Italian trained and principally a sculptor (his father had been a cabinet-maker to Christian IV). Simultaneously engaged on sculptural enrichments at Hampton Court and in his mid 60s, Cibber took on this role without charging a fee. The church was completed in time to be consecrated on 15 November 1696, having cost £4,608 5 2.1

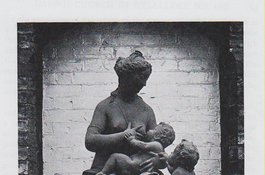

The Danish–Norwegian church was a simple quoined brick rectangle with an apsidal east end. With its slight transeptal emphasis, implying a cross-axial layout, and the oculi above the outer-bay windows, it looked to models in London’s suburbs, not least St Mary Matfelon Whitechapel, as much as to post- Fire City churches. This is an architecture that is in keeping with what might be expected from the likes of Butcher and Woodstock. The cherub-keystones are likely to have been a Cibber touch. Below the clock tower and belfry to the west, the façade sported lead figures by Cibber representing Charity, flanked by Faith and Hope. These were preserved on the site until 1908 when they were acquired by the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen. Around the church’s 125ft by 75ft plot there was a dwarf brick wall with iron palisades. This was said to be in need of replacement in 1773, but seems to have endured if it was not replaced.

The interior was cross-vaulted with a domical centre articulated by a stuccoed wreath. There were two west galleries in which there was a Father Smith organ. Prince George gave an oak pulpit that had been made by Grinling Gibbons for James II’s Roman Catholic chapel in Whitehall Palace. With carved evangelist figures and otherwise richly ornamented, it was on the north wall opposite a canopied royal pew enclosed with sash windows and lined with velvet. An elaborately aedicular Corinthian altarpiece carried large wooden figures, of Moses and St John the Baptist on pedestals, these probably by Cibber, with St Peter and St Paul above, perhaps not his work. A painting above the communion table that appears to represent the Last Supper was replaced at an unknown date by a depiction of the Agony in the Garden. The wooden figures and the painting were moved in the 1870s to the Danish Seamen’s Mission Church in Poplar, and thence to the Danish church of St Katharine’s, Regent’s Park. The pulpit was sold, its whereabouts, if it survives, are unknown.2

Cibber (d.1700), and his playwright son Colley Cibber (d.1757) were both buried in the vaults under the east end of the church, which survive. Among others interred here were Albert Borgard and Daniel Solander (d.1782), the Swedish botanist who sailed with Captain James Cook.

The Dano-Norwegian union ended in 1814, but Frederick VI, now the King of Denmark, continued briefly to support the church, its congregation reduced as a result of Danish–British conflict in the Napoleonic wars. In 1816 the church was transferred to trustees operating as a charity and let out, going in 1825 to the Rev. George Charles (Boatswain) Smith of the British and Foreign Seamen’s Friends, for a mission that became known as the Mariners’ Church (also the Bethel Union). Smith’s eccentricities antagonised Anglicans and alternative uses were sought. Around 1840 the Swedish church close by to the east in Prince’s Square (opened in 1729) proposed absorbing the Danish church. Smith failed to pay the rent and was imprisoned for debt in 1845 (see St Paul, Dock Street).

The building reopened in April 1845 as the British and Foreign Sailors’ Society’s Church. Then in 1856 it was let to the Rev. Charles Fuge Lowder to be part of his Anglo-Catholic mission attached to St George in the East, where his fellow Tractarian, the Rev. Bryan King, was based. Under Father Lowder the building was called Saint Saviour and the Cross chapel, alternatively St George’s Mission Chapel, and used for high-church worship, the imposition of which met riotous opposition in the parish of St George in 1859–60. The Danish charity was reformed in 1859 and there was a limited revival of use of the Wellclose Square church by a Danish congregation in the 1860s. The charity sold the church via the Bishop of London’s Fund in 1867–8 to the ministers and trustees of St Paul, Dock Street. The vaults were ordered closed, and the church was demolished in 1869.3

-

The National Archives (TNA), SP44/345, f.17; PROB11/551/212: British Library, Add MS 37232, f.100: Ernst Fridrick Wolff, Samlinger til Historien af den Danske og Norske Evangeliske Lutherske Kirke i London dens Opkomst Fremgang og Tilstand, 1802, pp. 32–3,48,391–442: John Southerden Burn, The history of the French, Walloon, Dutch and other Foreign Protestant Refugees settled in England, etc, 1846, pp. 241–3: Howard Colvin, A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects 1660–1840, 1995 (3rd edn), pp. 248,1079 ↩

-

London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), SC/SS/07/024/238–41; P93/PAU2/142; P93/PAU2/197/1–2: National Maritime Museum, S9597: Wolff, Samlingen, p.363: Gentleman’s Magazine, 1827, part I, p. 304: Harald Faber, Caius Gabriel Cibber, 1630–1700, 1926, pp. 61–6,70: Survey of London, vol. 43: Poplar, Blackwall and the Isle of Dogs, 1994, p. 117: Margaret Whinney, Sculpture in Britain, 1530–1830, 1992, p. 442 ↩

-

LMA, P93/PAU2/118–27; P93/SAV/001: The Builder, 17 April 1869, p. 313: Faber, op. cit.: Survey of London notes from Swedish Church Records, Box OII/1: Post Office Directories: J. S. Burn,op. cit., p. 243: Faber, op. cit., pp. 67–70: information kindly supplied by Mark Willingale ↩

St Paul’s Whitechapel Church of England Primary School

Contributed by Survey of London on Oct. 9, 2018

In 1858 the Rev. William Weldon Champneys, Rector of Whitechapel, proposed attaching schools to St Paul, Dock Street, which had opened in 1847. Five years later, an infant school opened on the first floor of 21 Wellclose Square (it soon moved to No. 12), and St Paul’s newly appointed rector, the Rev. Dan Greatorex, raised an alarm about attempts by the Anglo-Catholic clerics based at St George in the East, the Rev. Bryan King and the Rev. Charles Fuge Lowder, to gain control of his district and to buy the Danish Church of which they were then tenants, for an extension of their Romanizing project. With support from the Bishop of London, A. C. Tait, Greatorex was able to secure control of the district in 1864 for St Paul, Dock Street, and thus to evict Lowder and the churchmanship he represented from Whitechapel. Greatorex and his chapel wardens acquired the former Danish church through the Bishop of London’s Fund in 1867–9 for the purpose of providing Church of England schools for local working-class and poor children, especially those of seamen. First funds were secured and an appeal was launched with a target of £4,500.1

What was to be St Paul’s National Schools were intended for a district with a population of 9,668, mostly seamen, dock and wharf labourers and their families, estimated as being a third Anglican, a third Catholic and Jewish, and a third of ‘no distinctive sect’. The schools would accommodate 150 boys, 150 girls and 300 infants, and ‘counteract the vice and demoralization which abound’.2 Greatorex’s building committee embraced notables from both Whitechapel and Wapping and included the Rev. James Cohen, Rector of Whitechapel, Lacy Hipwood, Secretary, Charles Addingham Hanbury of Truman’s brewery, Augustus W. Gadesden and William Straw of Leman Street, John Whyte of Upper East Smithfield, Henry Sadler Mitchell of Prescott Street, Joseph Loane, a Dock Street surgeon, John Butler, a haberdasher of 42 Wellclose Square, William Henry Graveley, a City surveyor, Capt. Francis Maude, Chairman of the Sailors’ Home, Capt. George Troup, and Thomas Joyce and Robert Henderson from Wapping.

First plans were for conversion of the church, with an inserted floor for boys’ and girls’ classrooms above space for infants, and the addition of a large new east range, at an estimated cost of £6,000. By April 1869 it had been agreed that the chapel could not be converted, its north wall being said to be badly out of upright, and that it would be necessary to erect a new building, though ‘not without regret’,3 as was claimed, and not without opposition that favoured an open recreation ground. The architects were Greatorex and Co., the rector’s brothers, Reuben Courtnell Greatorex and Simeon Greatorex, of Westbourne Street Mews, Hyde Park Gardens. The contractor was Thomas Ennor of Commercial Road, and Joseph Fairer made the schools’ clock. Gadesden laid the foundation stone on 21 December 1869 and the Prince and Princess of Wales (Princess Alexandra being Danish) opened the schools on 30 June 1870, with a roll of 143 boys, 165 girls and 283 infants. The final cost of the building all told was recorded as £7,193 10s, with £7,955 3 9 having been raised.4

The Gothic schools building, of stock brick with red- and white-brick and Portland stone dressings, occupied the whole of the church’s walled plot (125ft by 75ft) and reused church foundations. There were long boys’ and girls’ classrooms either side of a spine wall, raised on arcades above undercroft playgrounds. Infant classrooms were in a separately roofed east range. Houses for the master and mistresses flanked the twin west entrances above which there rose a clock tower. Open trefoils mark all the gables, and some original window tracery survives. Cibber’s figure of Charity breastfeeding an infant stood on the stone plinth in the central recess below the dedication stone until 1908. Lettering is in relief, not inscribed, and a ship surmounted the clock tower’s weathervane.5

Attendances rose to 199 boys, 168 girls and 382 infants in 1874 before declining to 97 boys, 111 girls and 198 infants in 1891; large numbers were Jewish. By this time support came from the Whitechapel Foundation, then the London County Council took on responsibility. Improvements were mooted as necessary in 1905 and loans were approved. The infants’ department was altered in 1908, externally by the raising above the eaves of the three central windows of the east elevation, internally by the removal of an organ, probably rescued from the Danish church. There were also two triple-seraph sculpted bosses in the schoolroom’s ceiling, one of which still survives. These works were overseen by T. J. Bailey for the LCC, with G. E. Weston as the builder. Attendances fell to 174 mixed and 82 infants in 1929, and a reorganisation scheme that was approved in 1939 fell foul of the war.6

In the planning of wider post-war reconstruction, consideration was given to moving the school in the 1950s. Instead, it was extended to the south in 1960–2, with Thomas F. Ford & Partners as architect and William Verry as contractors for an assembly hall and kitchen. Princess Margaret opened the hall on 20 February 1962. It has laminated timber arches with the profile of an inverted ship’s hull. A copper model of a fully rigged ship on the south entrance elevation of the hall was a weathervane on St Paul, Dock Street, repaired and regilded in 1953, and moved around 1990. An advertisement for a new Headmaster in 1966 sought ‘Liberal-Catholic’ churchmanship for a ‘challenging multi-racial area’.7 A prefabricated nursery room went up in gardens to the south-west in 1970. The school was listed in 1973 and numerous minor alterations followed. The playground undercroft had its former openings definitively bricked up in 1985–6 with the original tracery emulated. A major refurbishment programme in 2010–11 overseen by Wilby & Burnett, architects, included T-plan brick-faced classroom extensions to the south-west (nursery and reception) and east (first and second years).8

-

London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), P93/PAU2/030–034,117,123,127,136–7 ↩

-

The National Archives (TNA), ED103/111/1 ↩

-

LMA, P93/PAU2/145 ↩

-

TNA, ED103/111/1: LMA, P93/PAU2/127,137,140–1,143–5, 198/1–4: The Builder, 10 April and 17 July 1869, pp. 291,569; 9 July 1870, p. 551: Illustrated London News, 9 July 1870, pp. 37,42 ↩

-

LMA, P93/PAU2/137,195/1–4 ↩

-

LMA, P93/PAU2/104,132–4; District Surveyors Returns: TNA, ED21/12137,35341,57371; ED49/5165: London County Council Minutes, 30 May 1905, p. 2083; 10 Oct. 1905, p. 1071; 13 Feb. 1906, pp. 246–7; 19 Nov. 1907, p. 1093; 22 Dec. 1908, p. 1481; 19 May 1909, p. 1226 ↩

-

LMA, P93/PAU2/247 ↩

-

Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives, L/THL/D/1/138; L/THL/B/1/2/30; Buildilng Control file 25297; P/RAM/6/29: LMA, P93/PAU2/248: Church Times, 27 Feb. 1953: Tower Hamlets planning applications online ↩

St Paul's School, Wellclose Square, with market in August 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul's School from the east, August 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul's School from the northeast, October 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul's School, Wellclose Square, from the south in 2016

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul's School from the west, October 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul's School, detail of west entrance, October 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul's School from the north, October 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul's School, clocktower from the southeast, October 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul's School, ship weathervane, October 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul's School, ship from St Paul's Church on south elevation of assembly hall, October 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul's School, seraphs by Caius Gabriel Cibber at ceiling of early years (former infants') classroom, October 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul's School. early 1960s assembly hall from the north, October 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul's School, Wellclose Square, in 2016

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul's School, staircase in former south schoolmaster's house, October 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul's School, Wellclose Square, entrance detail

Contributed by Peter Guillery

Caius Gabriel Cibber's statue of Charity

Contributed by Survey of London

St Paul's School playground from the west, October 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul's School, view to south entrance, October 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul's School, entrance hall on south side of former covered playground, October 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Paul's School, early years (former infants') classroom, view to south, October 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall