Lily Austin at the Roebuck Public House

Contributed by Pete on Feb. 21, 2017

My mum was born above the Roebuck Public House in Brady Street in 1928. A

stairway had to be installed at the rear of the premises so she didn’t have to

go through the pub to get to her lodgings above. She would run up the stair as

they passed the outside urinals. The urinals were full of tall men dressed all

in black with beards and black hats.

Her dad (a horse-keeper) worked nearby and she accompanied her mum around the

local streets with a barrow selling cat’s meat (horse meat) at a penny a bag.

She was attending the Roan School for Girls around 1942/3. I have her

autograph book signed by her schoolmates along with her school badge.

My mum was the youngest of a family of at least five siblings. There were two

boys, one killed in the war, one killed in a motorbike accident, leaving three

girls: Marie, Daisy and my mum Lily. Lily got married from 279 Whitechapel

Road (the Working Lads Institute) aged 16 years in July 1945. Perhaps she

shared a room there with her family during the war years. Next I remember was

5 Ireton Street, where I was born under the front window in January 1951. It

seems I had a crib hanging in the alcove beside the fireplace which my dad

made out of used orange boxes, tasking my mum to straighten out the nails for

this re-use.

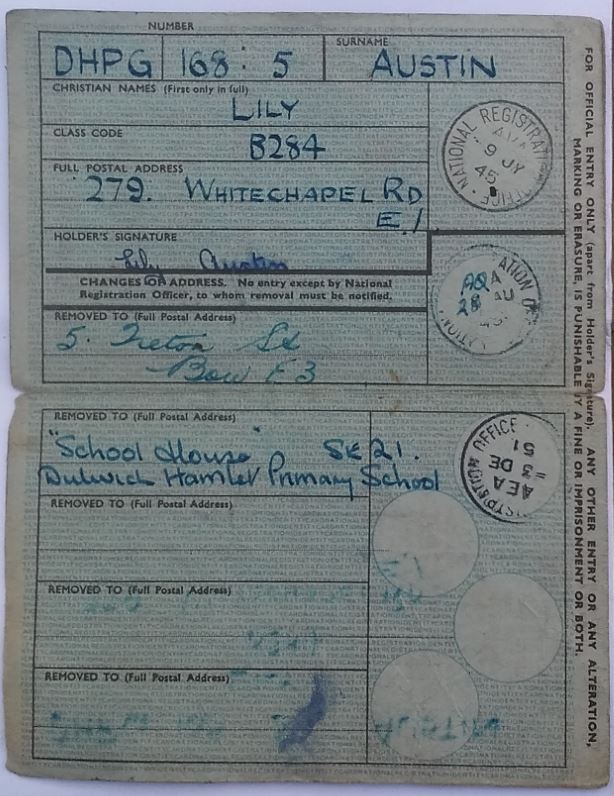

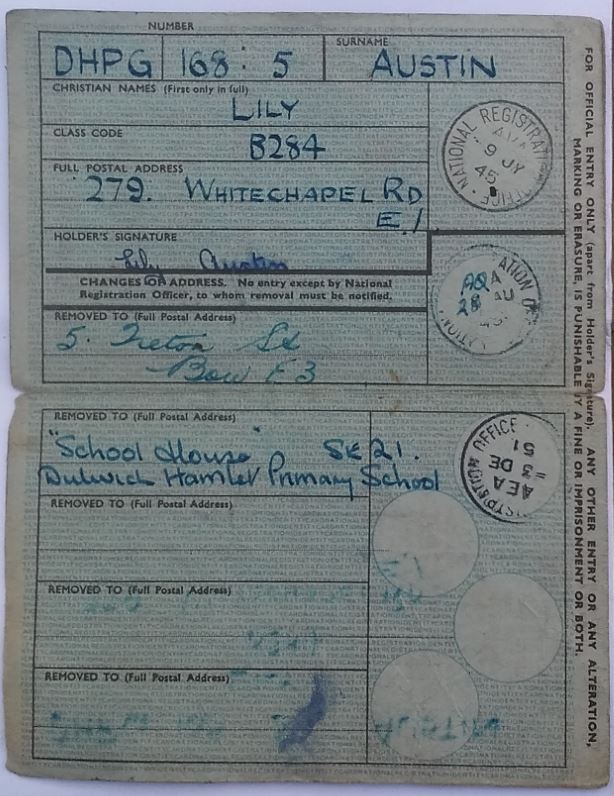

Mum’s National Identity Card

After a while my dad went into training to become a school keeper and we moved

off to Dulwich Hamlet School. Mum wasn’t very impressed with this move saying

everybody there looked down on her and when she went shopping she was

surrounded by domestic servants! We didn’t stay there long.

Mum and me aged 1 year (with a hair style which demanded a lot of spit on her

part). Why did mums do that??

A Grocery Shop and a Brewery in Wartime Whitechapel

Contributed by norman on May 30, 2017

I am a product (pre-war) of Whitechapel. Mid 1930s, my father, Wolf

Goldenberg, rented a shop at 7 Brady Street, from a Mr. Cockerell and the shop

was known as Cockerells.

We lived above the shop where we had two bedrooms one of which I shared with

my brother. Our bathroom, toilet and kitchen were located in the open air on

what was the roof of my dad's storage room at the back of the shop. Somehow my

mother managed to keep us clean and cook our meals. My bedroom overlooked an

area that belonged to a stonemason and it had a lot of tombstones waiting to

be used. Whitechapel Station was a little way beyond. I remember being kept

awake by the shunting of the trains in the middle of the night.

When the war started, together with my gasmask, I was evacuated alongside my

school - Robert Montefiore - to a village called Mepal just outside Ely in

Cambridgeshire. At six years old I was very unhappy, and as nothing warlike

seemed to be happening at home for the first nine months of the war, my

parents decided to bring me home to Brady Street where I was when the Blitz

started.

My father left during the war owing to the difficulties involved with food

rationing and coupons, and customers constantly asking for an extra ounce of

this or that over and above the rationing. I was re-evacuated to a village

called Stretham, also just outside Ely, where I went to school and stayed

until the end of the war. I was billeted with a Jewish family who had three

kids of their own and who treated me like dirt. My folks eventually moved to

Dollis Hill.

Number 5 Brady Street was occupied by Alec the barber. Number 9 was a stone

mason by the name of Levy (whose relative coincidentally now lives near me in

North London).

The Ducking Pond and adjacent early developments

Contributed by Survey of London on Jan. 3, 2018

Part of a natural watercourse known as the Black Ditch that flowed through

Stepney from Shoreditch to Limehouse formed the irregular northernmost

boundary to this part of the parish of Whitechapel. This was canalised as a

common sewer that turned south outside the parish to the east (across what

became the Albion Brewery site), and was used as part of a burial ground

during the plague of 1665. origins of Whitechapel’s Ducking Pond, so called by

1715 when it was leased to Joseph Gosden (John Bosley took it for 90 years in

1739), may have to do with this watercourse. The pond has been associated with

punishments, as by see-saw and as connected to witch-trials, and it was close

to the manorial court and a pound that stood to the east beyond Mile End Gate.

However, it is more likely that its name derives from the sport of setting

dogs on ducks, as with other sites of the same name on London’s margins in

Clerkenwell and Mayfair. Even so, it was a sufficient body of water for women

twice to be found drowned therein, in 1753 and 1798. In 1768 it was resorted

to by rebellious silk-weavers, known as ‘cutters’, for the destruction of

cloth produced below piecework rates. The Ducking Pond was perhaps a casualty

of water extraction for distilling, carried out on a large scale to the north

from the 1760s. Its site was built over in the early years of the nineteenth

century when what survives in part as Winthrop Street was formed as Watson’s

Buildings. The name Buck’s Row was in use by 1780 and had wholly superseded

Ducking Pond Row by the 1840s.

From the manorial Court House on the corner with what is now Court Street

eastwards, the south side of Ducking Pond Row was densely built up by the

1740s. Development behind the present site of 287–293 Whitechapel Road can be

traced back to Henry Allam, a Whitechapel blacksmith and gunner, who leased

the land in 1591. At the beginning of the eighteenth century ownership passed

to Edward Elderton, a grazier and butcher who held lands south of Whitechapel

Road. In 1722, when this property to the west of Yorkshire Court was taken by

John White, a tallow chandler, there were two new houses. Among the buildings

on Ducking Pond Row was White’s melting house, a forerunner of a

slaughterhouse on land that became part of the Spencer Phillips estate.

The road that is now Brady Street (previously Ducking Pond Lane, then extended

as North Street and again renamed in 1875) was a 40ft-wide cart- or horse-way

in the 1670s leading to meadows owned by Ralph Thickens and tenanted by

Abraham Carnal (or Carnell), a brick-maker. West of his property a 60ft

frontage on the north side of Ducking Pond Row was leased from the manor for

500 years in 1672 by Thomas Blakesley, a Whitechapel weaver. Ducking Pond

Lane’s frontages south of Ducking Pond Row were thickly built up by the 1740s,

incorporating to the west a court of eight small houses known as Pratt’s

Rents. From 1761 there was a Jewish cemetery to the north, across the parish

boundary in Bethnal Green.

Whitechapel Distillery aside there was a lot more noxious land use in the area

to either side of 1800. Matthew Horne had a bone house on Ducking Pond Lane in

the 1770s, and Thomas Whitwell, probably another distiller, was near White’s

Row in the eighteenth century. George Monks, a night-man, took a large plot of

land on what was to become the west side of North Street in 1797 for the

dumping of night soil. William Monk had at least some of this as a bone ground

by 1822 when this corner of the parish was ‘wholly occupied by Horse

Slaughterers, Nightmen and Bone Choppers’. Monk also held what had been

the tallow chandler’s site on the south side of Watson’s Buildings west of

what was now Nelson Court. By 1833 his slaughterhouse there had been taken by

William Barber. It kept going as one of Harrison Barber & Co.’s seven

London slaughter depots, with redevelopment in 1901–2, only closing around

1950 (see Lily Austin's memories alongside this account).

The wedge of land between Buck’s Row and Watson’s Buildings (Little North

Street by 1850, then Winthrop Street from 1883), which had been taken as an

extension of the distillery in 1829, was solidly built up with terraces of

sixty almost back-to-back two-storey houses following a lease of 1861 to

George Torr who ran a manure works to the north. Building on Little North

Street continued into the 1870s and the houses stood into the 1970s. Buildings

along Brady Street including the Roebuck public house at No. 27 on the Durward

Street corner stood until 1996. Winthrop Street itself retained

nineteenth-century granite setts.

Shopping-mall schemes

Contributed by Survey of London on Jan. 4, 2018

From 1972 to 1988 there were plans for a large shopping mall to the north of

Whitechapel Road and Whitechapel Station. These were initiated by the London

Borough of Tower Hamlets, which owned land north of Durward Street and was in

the process of acquiring Greater London Council owned property, and planned

co-operatively with London Transport, which owned most of what lay to the

south of Durward Street. A first scheme incorporated substantial office and

residential elements and proposed building above the railway line. The

factories north of Durward Street and the housing between Durward Street and

Winthrop Street were cleared in the early 1970s, leaving just the coal-drop

viaduct, Rosenbergers and Brady House on Durward Street, Brady Street

Dwellings, and a garage immediately south of the Jewish Burial Ground in

Bethnal Green.

The Shankland Cox Partnership put forward four development options in 1975,

soon reduced to three, ranging in extent from just the east side of

Whitechapel Station to Brady Street, to all the way to Vallance Road in the

west. Redevelopment planning extended well northwards into Spitalfields and

Bethnal Green. Abbott Howard, architects, took forward a preferred scheme

before 1979 when the Council briefed Sam Chippindale Development Services to

prepare a plan for almost fourteen acres ‘loosely based on a Brent

Cross/Arndale theme’; Chippindale, a founder of Arndale, had not previously

been active in London. Through Trip and Wakeham Partnership, architects,

this had become a huge project (larger in fact than Brent’s Cross) extending

to the northern boundary of the parish, intending 800,000 square feet of

retail including six or seven department stores, 300,000 square feet of office

space, flats and parking for 1800 cars and a bus station.

There was perceived competition from Surrey Docks, but all seemed set to go

ahead in 1983. However, two big retailers pulled out and Chippindale, voicing

doubt (the project ‘hadn’t got a cat in hell’s chance of succeeding’), was

sacked in 1985. The scheme’s commercial viability was further questioned, but

concerned at being the only London borough both not to have a large retail

centre and expecting a population increase in the 1980s, the Council issued a

new development brief. Competing proposals included a scheme by Inner City

Enterprises submitted with the Tower Hamlets Environment Trust on behalf of

the Whitechapel Development Trust. This became known as ‘the community plan’;

its architects were CZWG. A more commercial rival (more offices and parking,

less residential) from Pengap Securities Ltd working with Chapman Taylor

Partners was favoured. Pengap was taken over by the Burton Group in 1987 and

the project was passed around, to former Pengap directors as Wingate Property

and Investment, then to Chase Property Holdings and on to Trafalgar House with

Consortium Commercial. The scheme they submitted and gained permission to

build in 1988 would have had a large domical central feature and a nine-storey

tower on Brady Street. It would also have meant clearance of 235–245 and

287–317 Whitechapel Road. But negotiations unravelled and by the end of the

year the project had died, its abandonment said to be connected to proposals

for the Grand Metropolitan owned Albion Brewery site. Meanwhile there had been

vast quantities of fly-tipping on the empty land, to a depth of 2–3m.

What had been the Kearley & Tonge site south of Vallance Gardens was used

for car auctions, as a lorry park and as a Sunday market for second-hand goods

in the 1980s and 90s. A spin-off from Brick Lane’s then gentrifying market,

this was misleadingly referred to as Whitechapel Waste, and more accurately

described as the 'kalo' (Bengali for black) market.

Kempton Court

Contributed by Survey of London on Jan. 4, 2018

Kempton Court (2 Durward Street and 7–23 Brady Street) was an early project by

Sean Mulryan’s Ballymore Properties Ltd, previously Kempton Homes (London)

Ltd. Built in 1996, the development comprises 110 flats with ground-floor shop

and office units on Brady Street that have since 2004 housed The Haven, an NHS

and Metropolitan Police sexual-assault referral centre. Plain, even austere,

the long four-storey brick elevations are punctuated by gables over recessed

bays with balconettes. The street ranges conceal an inner block aligned with

the railway cutting. The estate has been gated since 2005 following complaints

from residents about security.