72–86 Alie Street

Contributed by Survey of London on July 31, 2020

Sir Stephen Evance held a 120ft frontage on the south side of Alie Street between Rupert Street and Lambeth Street from 1686, having acquired John Hooper’s Leman estate leases of 1682. Sir Caesar Child, Evance’s legatee in 1712, extended the lease of 1682 in 1722 after he resolved his inheritance. That seems to have led to the development of this Alie Street holding. It had been built up by 1733 with eight houses, later Nos 72–86. Though comparatively narrow with three windows squeezed into 15ft fronts, these houses were substantial, two rooms deep and of three storeys and attics over area-lit basements, their doors with projecting hoods on carved brackets. Child’s son- in-law, Jonathan Collet, who, like Evance, was a director of the Royal African Company, renewed leases in 1744 and the row formed part of Leman estate property acquired by Edward Hawkins in 1779 from John Newnham’s trustees.1

The terrace at 72–86 Alie Street was popular with naval men. A Capt. Colebatch was in the westernmost house by 1733, succeeded from 1756 by Capt. Charles Robinson (d. 1781). Capt. Purser Dowers (1706–77), a shipwright’s son from a family of Dutch origin, lived in some style in one of the more easterly houses from 1756, with his ‘housekeeper’ Elizabeth Curtis to whom he left a substantial legacy and the well-appointed contents of the house, including silver, porcelain and two four-poster beds. Four of the row’s houses were destroyed in the Second World War, the other four stood till 1960.2

The Lambeth Street area in the eighteenth century

Contributed by Survey of London on Aug. 18, 2020

The eighteenth century saw gradual industrialisation of the Lambeth Street area. The west side of Rupert Street was from an early date effectively a service yard for Leman Street’s properties. On the triangle between Rupert Street and Lambeth Street commercial activity increased, especially at the south end. Joseph Bagnall, who had married John Hooper’s widow Margaret and sold up a huge sugar business in 1722 that included premises on Leman Street, took a short lease in that year of an already existing sugarhouse on Lambeth Street, probably on the west side adjacent to Johnson’s Court. Successive owners enlarged these or nearby premises, Christian Schütte in the 1730s, and William Baker in partnership with John Carter in the 1740s. Baker over- extended himself and forged nearly £1,000 of East India Company warrants for which he was hanged at Tyburn in 1750. Successors were John Walker and James Richdale (d. 1799).1

Further north off the west side of Lambeth Street there was a large stable yard by the 1730s that came to be associated with the Flying Horse public house. Other pubs in the area were the White Bear (sometimes the White Hart) on the east side of Lambeth Street immediately south of the alley that projected Johnson’s Court into Masters’ Garden, the Crown (sometimes the Crown and Sugar Loaf), on the south-east corner of Rupert Street and Johnson’s Court, and the White Hart at the junction of Rupert Street and Lambeth Street on Hooper’s Square. Domestic industry can be instanced by James Purdey, a blacksmith whose family occupied a house on Lambeth Street’s east side (No. 30) from the 1750s to the 1790s. His son, James Purdey (1784–1863), rose to prominence as a gun maker.2

-

London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), Land Tax Returns (LT): Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives (THLHLA), P/PAG/1/4/1/2–7: Whitehall Evening Post, 3 Jan 1751: Select Trials … at the Old Bailey … 1741 to 1764, 1764, pp.64–71: Bryan Mawer's sugar-industry website ↩

-

LMA, LT; CLC/B/192/F/001/MS11936/399/639775: THLHLA, P/PAG/1/4/1/1; P/PAG/1/4/1/4: Ancestry: Post Office Directories: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography sub Purdey ↩

Whitechapel Police Office (demolished)

Contributed by Survey of London on June 5, 2020

A court and police office was built at the north end of Lambeth Street’s west side following the Middlesex Justices Act of 1792, which reformed magistracy and formalised and extended London’s police courts, dividing the capital into eight police districts. The Lambeth Street premises covered one of these districts for Whitechapel, and thereby accommodated three stipendiary magistrates and six police officers. No image or description of the Whitechapel Police Office survives, but the small premises included offices for the constables, a waiting room and cells, as well as a courtroom. Like other contemporary police courts, it must have been confined and crowded. (Sir) Daniel Williams (_c._1753–1831), a surgeon and apothecary and previously a magistrate for the Tower Liberty, held corrupt sway here as senior magistrate from the outset until his death. The Whitechapel Police Office closed in 1844, its functions superseded since 1829 by the Metropolitan Police, represented locally on Leman Street. Williams’s successor claimed in 1837 that his officers contented themselves with pursuing crimes for which a fee could be earned, the prosecution of other offenders being left to the new force. The office was repurposed or more likely rebuilt as a lodging house.1

-

London Metropolitan Archives, Land Tax returns: Richard Horwood's maps of London: Post Office Directories: James Grant, Sketches in London, 1840, p. 199: West Kent Guardian, 23 Dec 1844, p. 7: Jerry White, London in the Eighteenth Century, 2012, pp. 433–7: Julian Woodford, The Boss of Bethnal Green: Joseph Merceron, The Godfather of Regency London, 2016, passim: Clive Emsley, The English Police: A Political and Social History, 1991, p. 29 ↩

Commercial Road Goods Depot with warehouse and branch line (demolished)

Contributed by Rebecca Preston on May 11, 2020

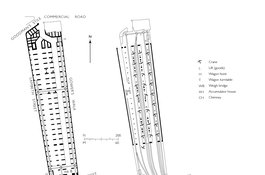

The Commercial Road Goods Depot was a huge railway complex. Sited to the north of the London and Blackwall Railway, it was built in 1884–7 by the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway Company (LTSR) as a receiving and forwarding depot for merchandise dealt with at the East and West India Dock Company’s Tilbury Docks, which opened in 1886. The premises comprised ground-level vaults with viaduct-level sidings, shunting yard and a branch line, and a goods station below a colossal warehouse that was demolished in 1975. The site on the west side of Gower’s Walk, twice redeveloped since, is largely occupied by Berkeley Homes’s Goodmans Fields development. The heft of the warehouse is most evident in aerial views.1 The goods depot was conceived in 1881 by the East and West India Dock Company, which approached the London Tilbury and Southend Railway Company (LTSR) with a view to creating a direct link between its then projected Tilbury Docks and central London. This was an intensely competitive period in the Port of London and the joint-venture scheme was a necessary response to the opening of the Royal Albert Dock by the London and St Katharine Dock Company in 1880. With ships of ever-increasing size, the older closed-in up-river docks could not compete with large rail-connected docks further downstream. The depot was thus designed in part to supersede the London and St Katharine Dock Company’s up-river facilities to the south of Whitechapel. But competition led to crisis and soon after the depot’s completion the dock companies went into joint operation in 1888, an arrangement that led to the formation of the Port of London Authority (PLA) in 1909.2

An Act of 1882 enabled construction of the depot and its connecting branch railway, despite objections from Whitechapel District Board of Works, which were met in a further Act of 1884. The legislation included provision for the creation of Hooper Street between Hooper Square and Gower’s Walk, and the extension of Pinchin Street in a northward curve to follow the line of the spur to the new depot. The Act also stipulated that the abutments of the bridges over Back Church Lane and Hooper Street were to be faced with white glazed bricks and be of ‘a reasonably ornamental character and design’.3

In 1884 the LTSR extended its land grab to include the German Church in Hooper Square, which was to be replaced by an hydraulic pumping station. The Mill Yard Seventh Day Baptist chapel and its minister’s house, three cottages and picturesque burial ground were other casualties. Disused burial grounds had to be dealt with, coffins removed to the City of London Cemetery, and 253 ‘old and dilapidated houses’ had been demolished by 1885. By 1887 the depot had displaced 2,579 people, without provisions for rehousing. The rule that no buildings should be erected on disused burial grounds was evaded because the sidings, station and warehouse were raised on vaults to the level of the London and Blackwall Railway.4

The LTSR general manager and engineer, Arthur Lewis Stride, and the East and West India Dock Company’s engineer, Augustus Manning, oversaw plans for the depot and warehouse. A first scheme of 1882 was rejected by insurers at the London Wharf and Warehouse Committee because the distances between fire- resistant walls in the warehouse were too great. The original five sub- divisions (known as risks) were reduced in size to form eight, which layout was approved in 1883. J. Mowlem & Co., favourites with the Dock Company, were employed as the main contractor and construction proceeded in 1884–5. The lower-level depot opened on 17 April 1886, to coincide with the grand opening of the Tilbury Docks. In the interim, the dock company had rented Hyatt & Parker’s Hooper Street wool warehouse, which the LTSR had acquired in 1883, to store tea and other produce. By February 1886 the warehouse was set to go ahead. Its hydraulic machinery was ordered from Sir W. G. Armstrong, Mitchell & Co., and contracts were placed for structural steel, 20,000 tons from Arrol Brothers in Glasgow. This may have been the largest amount of steel in any roofed building up to the time of its completion – the contemporary Forth Bridge used 50,000 tons.5

The warehouse opened in August 1887 and the LTSR leased it to the dock company for ninety-nine years at a rent equal to six per cent of the construction costs; in return, the LTSR guaranteed to carry a minimum of 200,000 tons annually between Tilbury Docks and the depot. This proved overambitious and, despite joint operation with the London and St Katharine Dock Company from 1888, the East and West India Dock Company went into receivership. According to Stride in 1903, the LTSR had spent ‘rather over a million’ on the depot and a further £1,067,000 on the houses that were cleared for the larger site, overall more than six acres – ‘the amount of business that it dealt with in no way justified its lavish proportions’.6

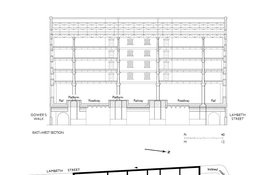

The site lay to the south of the west end of the Commercial Road, near the junction with Goodman’s Stile, the point of its main road entrance. It was bounded east and west by Gower’s Walk and Lambeth Street and south by the newly formed Hooper Street, over which the LTSR lines ran on a bridge, south to sidings or south-east where they joined the London and Blackwall line. The spur to the depot began outside Whitechapel on a brick viaduct that curved across Back Church Lane and Hooper Street on plate-girder bridges north into the goods yard where the locomotives stopped while the trucks were shunted to the ends of the lines beneath the warehousing. The extensive array of freely communicating vaults beneath the station and sidings was divided by Hooper Street. The vaults ran east–west with interconnecting round-arched openings through which tracks and platforms continued. Segmental arches facing Lambeth Street and Gower’s Walk were enclosed with brick, leaving triple apertures that were meshed in below panelled parapets. There were wagon hoists in the south-west corner of the yard and, an early addition, to the north-east, alongside Gower’s Walk. A vehicular ramp led up to the first-floor level goods station from Commercial Road; this was the main distribution level, where railway lines ran into the building between three loading platforms.7

The four-storey brick warehouse was constructed with riveted steel-plate girders, steel joists, Evans & Swains solid wood joist ‘slow-burn’ flooring, and hollow-cylindrical cast-iron columns.8 Despite being set back from the road and partially hemmed in by the Gunmakers’ Company’s premises, the building, the design of which can be attributed to Manning, was architecturally impressive. Its eighteen-bay front had its more closely spaced central six bays, including outer loophole bays, under a pediment in which the date 1887 flanked the LTSR emblem in a roundel. Somewhat narrower, the south elevation repeated this bay rhythm with an unadorned central pediment. There were iron-framed windows with opening panels. Perhaps most imposing of all was the 570ft length of the warehouse, which was spanned by nineteen three-window pitched-roof bays.

The top floor housed north-lit showrooms, with tea-bulking machines at the south end. The otherwise slate-covered roofs were also glazed above three open atria, big light wells lined by staircases and stone landings, and straddled by huge long-span steel girders. Each cellular floor was divided into thirteen compartments by internal brick walls, and there were about four acres of floor space. Lifts were later installed in the light wells.9

By 1892 the LTSR used the low-level vaults to store cheese, potatoes and grain, along with ‘case goods’ such as pianos, paper, glass and German toys. In 1896 the Wharf and Warehouse Committee’s Surveyor noted that all was ‘intermixed, no rational organisation evident’. Finding later in the year that piassava, a palm fibre, and whisky were now also held on site, he imposed a separation of the more dangerous materials at the north end of the depot. Browne & Eagle took multiple short lets on thirteen vaults for wool storage.10

The warehouse was lit by gas until 1905 when electric lamps were introduced. A two-storey office range was built in 1908, wrapped around the Lambeth Street and Goodman’s Stile corner. Another office building was added in 1923 when the LTSR became part of the London Midland and Scottish Railway Company (LMS).11

In 1906 the warehouse looked after a valuable collection of animals given by the Maharaja of Nepal to the Prince of Wales, who donated them to the Zoological Society of London in Regent’s Park. The creatures arrived at Tilbury ‘with two native keepers from the gardens of Calcutta’ and were held overnight at the depot before transfer. They included a rhinoceros, a baby elephant, a ‘fine tigress’, two leopards, two Himalayan bears, several varieties of deer, sheep and goat, and ‘some of the wild dogs that figure in Kipling’s “Jungle Stories”’.12 Two years later a cargo of Australian animals passed through the depot on the way to the Zoo.13

The enormous quantities of Indian and Ceylon tea blended and packed at the warehouse for the British military in the First World War appeared in patriotic press reports. By the 1920s, the lower levels served as an LTSR (then LMS) general stores and goods depot. The warehouse was bonded and used by the PLA and tenants as vast tea stores containing 78,000 chests.14 This business was interrupted by the Second World War.

Tilbury Shelter. In April 1940, the LMS agreed to the use of the Commercial Road Goods Depot as an air-raid shelter, provided Stepney Borough Council scheduled sufficient wardens to work under the company’s police, and that notices prohibiting smoking were put up in English and Yiddish. Initially the plan, probably a temporary measure, was to create two adjoining shelters, one for LMS personnel and a second ‘PLA Shelter’, above, for 1,400 members of the public. There were fears that ‘people caught in the streets would rush for this shelter as they did during the last war’.15 In preparation, the PLA’s engineers, Rendel, Palmer & Tritton, oversaw the bricking up of lower windows. However, when Stepney Council proposed using both the PLA and LMS sections as an official public air-raid shelter, the lower LMS section was refused approval by the Ministry of Home Security because it would involve ‘dangerously large concentrations of people in one shelter and because the Railway Company insisted that the roadway through the LMS sections be kept open for traffic’.16

The LMS Chief Engineer, R. C. Cox, noted that should the building be hit by a large bomb there was ‘a rather large calamity factor’, but that this was a necessary risk in the absence of other shelters in the area. In early September 1940, when the night raids of the Blitz began, the London Civil Division Region Officer told the Stepney Air Raid Precautions (ARP) Controller that ‘we must face facts as they are: this is not a public shelter but large numbers of people are using it as such and we cannot keep them out in present circumstances’.17 The LMS Goods Manager then agreed that about two-fifths of the low-level depot, the northern parts, could be used as a shelter under Stepney’s auspices with police protection, especially at Hooper Street, to keep out crowds.

The public, however, took possession of both the official (PLA) and unofficial (LMS) parts, thereby creating London’s largest air-raid shelter, which quickly became known as the Tilbury Shelter. Stepney was told that it must accept the situation and install sanitation. Works undertaken through Rendel, Palmer & Tritton were held up by labour shortages and were not complete in the official shelter until at least December. They eventually included bunks, lights, WCs, canteen facilities and medical supervision. When a head count was first taken in October 1940, some 8,000 people were found across both sections of the shelter. It was reported that on most nights the shelter held 14,000, thronging on a rainy night to form a ‘grim haven of 16,000’.18 There might have been exaggeration, but even so, in December official sources counted 4,244 people sheltering in the unofficial (LMS) lower-depot section, which remained ‘bare of amenities except hessian screened chemical closets’.19

This unofficial shelter was managed internally by the Communist Tilbury Shelter Committee, the leading organisers of which in its early years appear to have been its Secretary, a Mr Neidle, and Miss M. Ackerman, the Honorary Secretary, who gave her address as 153f Back Church Lane. To the PLA Police, which held jurisdiction at the Tilbury Shelter, the mass of people in the unofficial section in particular presented the threat of unrest whipped up by political agitators. The social research organisation, Mass Observation, sent observers to report on life in the shelter, ‘to make a complete study of the sociology of the largest underground concentration of humans yet known’.20 It noted that the efforts of the PLA Police to prevent the sale of the _Daily Worker_were usually outwitted by the occupants, ‘by no means all of whom are Communist sympathisers’, on freedom-of-speech grounds.21

Bunks were installed in 120 triple tiers in the PLA or warehouse section of the Tilbury Shelter in late October 1940. Within a month the vaults of the unofficial LMS or goods depot section had also been ‘fully bunked’.22 Nina Hibben, a Mass Observation worker, recorded that ‘The first time I went there, I had to come out, I felt sick. You just couldn’t see anything you could smell the fug, the overwhelming stench … there were thousands and thousands of people lying head to toe, all along the bays and with no facilities … the place was a hell hole, it was an outrage that people had to live in these conditions’.23 Despite such accounts, it seems that a kind of order prevailed as necessary routines were established. Life in the cavernous interiors of the Tilbury Shelter was depicted by Henry Moore, as an official war artist, by Edward Ardizzone and Feliks Topolski, as Civil Defence artists, and by Rose Henriques, a local resident and philanthropist.24

Both sections of the Tilbury Shelter were ticketed and monitored by the police, the official part accessed from Commercial Road and the unofficial part, now cut off by a brick wall, from Hooper Street. Closure of the unauthorised part of the warehouse, if tickets for other shelters were provided, was pursued and resisted in early 1941. Colin Penn, an architect with Communist sympathies, appears to have been to the fore among five architects from the Association of Architects, Surveyors and Technical Assistants who compared the Tilbury Shelter with alternative accommodation. On finding that the majority was less safe than the unofficial LMS section, the architects refused to recommend dispersal and occupants broke down the dividing wall. The police prevented a subsequent meeting, at which the architects were due to speak, called in protest against the eviction of the remaining occupants, which now numbered between 1,200 and 4,200 depending on the severity of raids. Public resistance to evictions and closure of the unofficial shelter continued. By May 1941, however, after the last major attacks of the Blitz, the unofficial sections were ‘not of course used at all now’ and were soon taken over as an official shelter in readiness for further bombing.25

There were still rumblings of discontent during 1942 and 1943, when low numbers of occupants were recorded. Eleanor Roosevelt visited the Tilbury Shelter with King George VI in October 1942. Other interventions were made by Rear-Admiral the Rev. A. R. W. Woods, Chaplain of the Red Ensign Club, Dock Street. In November 1944, a deputation from the Hindustani Markaz (Indian Centre), 14 White Church Lane, was received by the Ministry for Home Security, the Stepney ARP Controller and the High Commissioner for India. It complained of offensive behaviour, that officials had on numerous occasions insulted members of the local Indian community in the shelter or prevented their entry on racist grounds.26

Meanwhile the warehouse had itself been bombed. In early November 1940 a direct hit destroyed practically all of the roof and much of the top floor. This caused the PLA to wind up use of the building as a tea warehouse. A concrete flat roof was formed on northern parts of the warehouse around 1942.27 The south pediment survived until around 1949. The south part of the warehouse was also given a flat roof in the early 1970s.

Later use and clearance. At some point after the tea was removed in 1940 at least part of the warehouse above the shelters was taken over by the Ministry of Supply and the US Army, which formed a large canteen at the north end. By 1946 the US Army had left, the Ministry of Supply was storing ‘portable house’ or Prefab parts, and the PLA had returned with tea. The vaults and ground floor once again became an LMS goods depot.28

The Commercial Road depot became ‘non-operational’ on 3 July 1967; it was thus the last of the Whitechapel railway goods depots to shut. While the building’s future was debated, the PLA and British Railways retained some tenants, including J. Lyons & Co. Ltd, Buck & Hickman, and J. Walker & Co. Ltd. The site was implicated in unexecuted road schemes that included a tunnel with an approach road ‘plumb through the middle of the former depot’.29 In 1971 the depot was part of a GLC Special Study Area and, by 1973, of a Comprehensive Development Area encompassing all the land south of Goodman’s Stile and Commercial Road, between Leman Street and Back Church Lane, thus also including a good deal of the Co-operative Wholesale Society’s estate, which had been acquired by Standard Securities Ltd, part of the Norwich Union Insurance Company, before it was sold on to the National Westminster Bank which obtained an Office Development Permit for the whole site by 1975 and planning permission for a computer centre soon after.30

Demolition of the warehouse began in October 1975, leaving the sidings running south on arches from the Hooper Street bridge to the main line as a contractors’ working area. A circular brick gatepost in Goodman’s Stile survived a while and the skew bridge over Back Church Lane was gone by 1979. The sidings and Hooper Street bridge were taken down around 1986 to make way for Hooper Square.31

A trace of the depot survives in a brick structure with a run of fifteen arches at the bottom of Back Church Lane on its west side. This was built with the widening of the main line in 1892–3 at the end of the vaults under the depot’s sidings. It still stands facing Conant Mews because it carries the ends of the girders to the surviving railway line.32

-

Historic England Archives (HEA), EAW022337 ↩

-

Tim Smith, ‘Commercial Road goods depot’, London’s Industrial Archaeology, vol. 2, 1980, pp. 1–12; re-typed with annotations, Jan 2000, ww w.glias.org.uk/journals/2-a.html: Minutes of Evidence taken before the Joint Select Committee on the Port of London Bill, 9 July 1903, pp. 369–70: J. E. Connor, Stepney’s Own Railway: A History of the London and Blackwall System, 1984, p. 66: Peter Kay, ‘Commercial Road Depot’, The London Railway Record, no. 96, July 2018, pp. 82–98 ↩

-

45 & 46 Vic., cap. 143, pp. 15–16, 19, 21: 47 & 48 Vic. cap. 135, p. 4: Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives (THLHLA), L/WBW/11/10: Smith, ‘Depot’: Kay, ‘Depot’ ↩

-

THLHLA, L/WBW/11/10: London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), MBW/2649/34/09: The National Archives (TNA), HO45/9476/1081F; see also hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1885-04-14/debates/111d2e8d-57c6-4b67-9bf2-5390 66ff50d7/LondonTilburyAndSouthendRailwayBill(ByOrder): Globe, 15 Nov 1884, p. 6: Report of the Medical Officer of Health for Whitechapel, 1884, p. 6; 1886, p. 5; 1899, p. 19 ↩

-

LMA, MBW/2649/34/09: TNA, RAIL437/22, 3 Feb 1886, 13 Feb 1888; RAIL437/19, 11 March 1886; RAIL437/25, as cited in HEA, London historians’ file TH45: Smith, ‘Depot’: Kay, ‘Depot’: Jonathan Clarke,Early Structural Steel in London Buildings: A discreet revolution, 2014, pp. 299–300 ↩

-

TNA, RAIL437/19, 23 March 1887; RAIL437/22, 3 Feb 1886; IR58/84815/3252,3287: Minutes of Evidence, 1903, p. 370: Connor, Stepney’s Own Railway, pp. 67–8: Smith, ‘Depot’: www.pla.co.uk/Port-Trade/History-of- the-Port-of-London-pre-1908 ↩

-

LMA, CLC/B/017/MS14944/025, 9 March 1928; SC/PHL/02/0921/74/2974; District Surveyors' Returns (DSR): Ordnance Survey maps (OS) 1894, 1913: TNA, AN169/933: THLHLA, Building Control (BC) file 22123: Goad insurance plan, 1887 ↩

-

East London Observer, 18 July 1885, p. 3; 10 Oct 1885, p. 7: THLHLA, BC file 20995: Smith, ‘Depot’ Smith, ‘Commercial Road Goods Depot’: photograph by Paul Calvocoressi, 26 Oct 1973 ↩

-

TNA, AN169/933, p. 4: LMA, CLC/B/017/MS14944/001 p. 101; CLC/B/017/MS14944/043, pp. 354–5 ↩

-

TNA, RAIL437/19, 27 Jan 1886: LMA, CLC/B/017/MS14943/013, 21 Jan 1892, pp. 117–8, 21 July 1892, p. 194; /014, 12 July 1894, p. 176; /015; 13 Feb 1896, p. 172; 10 Dec 1896, p. 246, /016, 21 Jan 1897, p. 9; CLC/B/017/MS14942/008, 8 Oct 1896, p. 256: Smith, ‘Depot’ ↩

-

TNA, RAIL437/19, 1 Dec 1886 and 9 March 1887: LMA, CLC/B/017/MS14943/020, 22 June 1905; CLC/B/017/MS14944/005, 13 Oct 1910, p. 316: THLHLA, L/THL/D/D/2/30/70: DSR ↩

-

London Evening Standard, 11 June 1906, p. 8 ↩

-

Morning Post, 10 June 1908, p. 9 ↩

-

A. Crow, ‘The Port of London: Past, Present, and Future’, Town Planning Review, vol. 7/1, Oct 1916, pp. 9–10; THLHLA, BC file 20995: Pall Mall Gazette, 26 June 1916, p. 8: LMA, CLC/B/017/MS14944/024, 4 Aug 1927 ↩

-

TNA, HO207/860 ↩

-

Ibid ↩

-

Ibid ↩

-

Illustrated, 5 Oct 1940, p. 14: Daily Herald, 2 Oct 1940, p. 3; 7 Oct 1940, p. 3: Juliet Gardiner, Wartime: Britain 1939–1945, 2004, pp. 320–1: Constantine Fitzgibbon, The Winter of the Bombs, 1957, pp. 149–51 ↩

-

TNA, HO207/860 ↩

-

University of Sussex Special Collections, Mass Observation Archive, 486, Sixth Weekly Report for Home Intelligence, Nov 1940: TNA, HO207/860 ↩

-

University of Sussex Special Collections, Mass Observation Archive, 431, Survey of Voluntary and Official Bodies during Bombing of the East End (RF/NM), Sept 1940 ↩

-

TNA, HO207/860: www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/moore-shelter-scene- bunks-and-sleepers-n05711 ↩

-

As quoted in Gavin Weightman and Steve Humphries with Joanna Mack and John Taylor, The Making of Modern London, 1983 (edn 2007), p. 260: Tom Harrisson, Living Through the Blitz, 1976, pp. 116–27: Smith,‘Depot’ ↩

-

Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, N05708: Edward Ardizzone, Imperial War Museum, ART LD 1091: Rose Henriques, Museum of London, 47.37/3 ↩

-

TNA, HO207/860 ↩

-

TNA, HO207/860: THLHLA, Photographs, 347.1 ↩

-

TNA, HO207/860; AN169/933, p. 4: Smith, ‘Depot’ ↩

-

LMA, CLC/B/017/MS14944/043, pp. 354–5; CLC/B/017/MS14944/0532, Feb 1956, pp. 39–41: Goad insurance plan, 1960 ↩

-

TNA, AN169/933 ↩

-

TNA, AN169/933–4; /937 ↩

-

THLHLA, BC file 22123: Smith, ‘Depot’ ↩

-

Peter Kay, London’s Railway Heritage, vol. 1: East, 2012, p. 18 ↩

NatWest Management Services Centre, Goodman’s Fields (demolished)

Contributed by Survey of London on June 5, 2020

The National Westminster Bank (NatWest), the UK’s first ‘super bank’, was formed in 1967 from a merger of the National Provincial Bank and the Westminster Bank, both of which had begun computerizing their operations by 1962. In 1970, seventy per cent of the bank’s accounting was computerized and branches had started connecting to central computer systems in the City. By 1974 these were housed in two separate buildings in Coleman Street and St Swithin’s Lane, and the bank had a project in hand to establish a single building to house burgeoning back-office or ‘management’ services, including data processing and cheque clearing.1

To this end NatWest acquired both the obsolete Commercial Road Goods Depot from British Railways and all the redundant or under-used Co-operative Wholesale Society (CWS) buildings east of Leman Street. This vast Whitechapel site was attractive in that it would provide enough space for large operations while being close to the City, such proximity still being seen as essential. It was also in the ambit of the development area arising from the Gardiner’s Corner transformation. Ninety-five per cent of the bank’s processing was automated, but the rest of up to three million daily transactions were sorted by hand. Another attraction, therefore, was the availability of local labour, especially ‘female and semi-skilled. They will be carrying out repetitive, almost factory-like operations quite different from those required for normal office duties’.2

The prime mover in the acquisition of the property was Gerald Leigh (1930–2002), a racehorse breeder and property speculator since the late 1940s.3 In 1971 London and County Homes Ltd, of which Leigh was a director, had acquired much of the east side of Gower’s Walk from the CWS and others. Leigh approached the British Railways Property Board with a view to augmenting this holding with the goods warehouse site. However, when a deal was concluded in late 1973, it was Standard Securities Ltd whose offer was accepted, in preference to, among others, Associated Newspapers and National Car Parks. Standard Securities Ltd had been formed in 1971, with Leigh as chairman, as a holding company of a property investment group in which Norwich Union held a twenty per cent stake. By 1973 it claimed not just the Gower’s Walk property but also leasehold possession of the other former CWS buildings east of Leman Street, which, with the British Railways site, made a total of fifteen acres. Negotiations were soon underway with NatWest to lease the central part of the site for a large building for which NatWest secured an Office Development Permit in 1974. A downturn in the property market made it more attractive to sell the freehold to NatWest, which transaction was completed in September 1975. Planning permission had been granted a few days earlier, projecting redevelopment of much of the area between Leman Street and Gower’s Walk.4

The bank’s architects, Elsom, Pack & Roberts, had prepared a scheme for a large building, mostly set well back from the site’s frontages to Leman Street, Alie Street, Gower’s Walk and Hooper Street. It was to extend west only to Goodman Street and no further south than the former goods warehouse, leaving the major CWS buildings on Leman Street and the printing works at the south end of Lambeth Street and Goodman Street intact. The southern third of the site was reserved for future expansion. Higgs & Hill were appointed contractors in September 1975 and the site had been cleared by the end of the year. The building was topped out in May 1977, handed over in record time in July 1978 and formally opened on 25 April 1979, by when the name Goodman’s Fields had been revived as an address.5

The whole low-rise concrete-framed complex was encased in bright-red tuck- pointed brick. This was in keeping with the period’s ascendant anti-modernist preference for the supposed softening effect of brick, as exemplified by Darbourne & Darke’s Lillington Gardens through to Robert Matthew, Johnson- Marshall and Partners’ Hillingdon Civic Centre, respectively completed and begun in 1973. But any reversion to tradition here was particularly skin deep, the boxiness of the buildings reflecting the priorities of commercial architecture and the facility’s function as a cheque-clearing factory.6

The centre was essentially two interconnected establishments. The front or office complex comprised a central six-storey entrance block set back from and facing Alie Street, with its entrance marked by a deep canopy and a sweeping access ramp behind a bastion-like wall. This was flanked east by a forward projecting lower group of four ranges around a light well. Recessed bronzed aluminium windows lit all these front buildings. The entrance block linked south to a big, square-plan and largely windowless operations building, basically a shed full of computers. Four years after it opened, Richard MacCormac vilified the NatWest development for its lack of public space and for the way it ‘inverts the traditional street frontage and perimeter form of the city block into a dense block of building surrounded by a grass verge. The effect is to blast holes in the traditional fabric like a bomb’.7

Building Design had found the place correspondingly cheap and dowdy in its internal finishes. Show was limited to a double-height entrance hall, its brown-and-orange chevron-patterned carpet an allusion to the NatWest logo, with escalators rising to a mezzanine gallery. Offices had demountable partitions, so office space could be given over to computers or vice versa. For its time, the centre was highly energy-efficient, with heat generated by the operations building used to heat the offices. Electric vehicles were deployed, with their own charging station in the car park south of the operations building. With a workforce of 3,000 to 4,000, the centre included two restaurants, a basement bar, a nurse’s station, and a staff shop near the main entrance. The centre was soon extended with a six-storey wing to the west of the entrance block. Permission was sought in 1987 for extensive further service buildings to the south, but this was not followed through and in 1993 NatWest secured planning permission to redevelop the entire site with offices, though in the event only minor alterations were made for conversion of part of the operations building to office use. By 2000, when NatWest was taken over by the Royal Bank of Scotland, economies of scale and shifts from bulky computers running tapes to digital storage had generated a more concerted effort to redevelop the site.8 The centre closed in 2008 and was demolished in 2011–12.

-

The National Archives (TNA), AN169/937: Financial Times, 11 Aug 1969, p. 3: www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/national-westminster-bank- plc-history/: Ian Martin, ‘Centring the Computer in the Business of Banking: Barclays Bank and Technological Change, 1954–1974’, PhD thesis, University of Manchester, 2010, pp. 109, 149, 158–9 ↩

-

TNA, AN169/937: Martin, ‘Computer’, pp. 21, 159: The Times, 3 March 1975, p. 11: Building Design (BD), 4 May 1979, pp. 19–21 ↩

-

www.thoroughbreddailynews.com/leigh-dispersal-small-but- mighty/: The Times, 13 July 2002, p. 40 ↩

-

TNA, AN169/933; AN169/934; AN169/937: Financial Times, 28 March 1969, p. 32; 29 March 1982, p. 25: Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) Archives, NWB/2479 ↩

-

RBS Archives, NWB/2479: The Times, 5 Dec 1977, p. 18: Estates Gazette, 8 July 1978, p. 105 ↩

-

BD, 4 May 1979, pp.19–21: RBS Archives, NWB/2479; NWB/2739; NWB/2479: TNA, AN169/937: Tower Hamlets planning applications online ↩

-

Raphael Samuel, ‘The Return to Brick’, in Theatres of Memory, vol. 1: Past and Present in Contemporary Culture, 1994, pp. 119–35: Gavin Stamp, ‘Suburban Affinities’, Twentieth Century Architecture, _No. 10: THE SEVENTIES: Rediscovering a Lost Decade of British Architecture_, 2012, pp. 136–51 ↩

-

Architects' Journal, 15 June 1983, p. 61 ↩

Rashid Ahmed's thoughts on new housing in the area

Contributed by Survey of London on Feb. 20, 2018

Rashid Ahmed is a Rehab Support Worker at the Royal London Hospital, here he shares his thoughts on the new housing being built in Goodman's Fields, and in the area more generally.

"Housing has always been a problem for people, for residents of Tower Hamlets. Having heard that, "Oh, we're building new properties for the locals", that's not necessarily the case, because Tower Hamlets has always had a burden of a housing list for years.

It's not new, it's not a phenomenon, it's always been the case, but it's never accommodating the community needs. We don't need two, three bedroom flats, luxury flats. We need three to four, maybe even five or six bedroom houses and flats for the large families that need it.

I want to stay here, I want my family to stay here because my family wants to stay here. My friends want to stay here, their children want to stay here, everyone wants to stay. You don't want just to be uprooted because of financial reasons.

Everybody wants a bigger house, everybody wants a garden, no one is going to say no to it. The question is this, is that do you want to be uprooted or moved because you have no option? Do you understand? If you want a garden and a bigger house doesn't mean that you’re going to have to leave London to access that by compromising your family, your social network, all the other services that you have access to, and move into a strange remote area you have no idea what it could provide for you and your children.

Then develop a whole new social network not knowing what type of culture this area might have. Because you might be living in Britain, doesn't mean that there's a culture that's universal from place to place because it isn’t like that.

We know exactly what the future is looking like for us and it's looking bleak, simply because of the fact that we don't know who decided to quadruple or even beyond that the land prices, and alongside the house prices.

Londoners don't have a hope here of surviving or living in Tower Hamlets. For me, I’ve said to myself and I say to young people, “Listen and look at what the demographics is looking like for Londoners who were born and raised here for five to 10 year's time.”

I've heard for years people saying there's no place to build flats, we don't have homes for you. Every time I look and I should be documenting the expansion of new estates and new properties in Tower Hamlets..

..So it depends on how we’re talking about it, because to me it seems that when you start defragmenting people from their neighbours, and the people that they grew up with and they have close ties with as a community. And you start splitting them up, and you start re-housing them, and they start settling down. You’ve broken up -- you’ve taken the power away from the community. It takes generation to develop a community and this is why there isn’t a community anymore, people--

..We’re talking about quality of work, quality of life, and the competition with rent prices we’re not going to survive that. I’m working and I’ll be consistently working. [In] years to come my salary won’t survive my rent, I will struggle. We’re talking about gentrification, I will have no option but to move out.

I think that the fact that you’ve come and you’ve asked me this I feel quite honoured that I can actually voice for vulnerable people. I’m not someone who’s at risk per se at the moment of losing my home, or losing my job. I’m in a secure job I’ve been working at the NHS, I think probably just over eight years now.

But my concern is for people who aren’t in my position, to people who aren’t on the housing list, who are being forced out away from their families and their friends, and their place of work. Even if they re-house you and you have a job here, now you’re talking about an additional cost of having to travel in.

So those people like the nurses, doctors, the junior doctors, and in other departments of the health service who might not be on a higher salary, don't they need protection?

…It’s a fantastic borough. Tower Hamlets, there's no place like Tower Hamlets as it stands. We don't know what it's going to look like in five years, 10 years to come. Tower Hamlets is a vibrant place to live and grow up in, it's a fantastic place to have a child from."

Rashid Ahmed was in conversation with Shahed Saleem on 26.02.16. The interview has been edited for print.

Goodman's Fields - early history

Contributed by Survey of London on May 5, 2020

The area known as Goodman’s Fields since the sixteenth century extends west to east from Mansell Street to close to Gower’s Walk, and from north of Alie Street to south of Chamber Street. An estate of more than forty acres held by generations of Goodmans then Lemans was not much built upon until after 1680 when, under the ownership of Sir William Leman, the major roads were laid out. Houses quickly followed, some very large, with industries and trading mixed in, while significant open spaces survived into the nineteenth century. Railway interventions brought major change, and there have also been major late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century transformations.

Before development

Until the seventeenth century, Goodman’s Fields was an enclave of open pasture. The fields were sandwiched between ribbon development along Whitechapel High Street to the north and Rosemary Lane to the south. Much of the western half of Goodman’s Fields had formed part of what has been denoted the Eastern Roman Cemetery, where thousands of Londoners were buried between the late first and the early fifth centuries. Evidence of burials and cremations was noted by John Strype, who recalled that building work in 1678 unearthed ‘vast quantities of urns and other Roman utensils’.1 Recent archaeological excavations across the cemetery site have confirmed and continued to reveal the extensive scope of Roman activity. Residual memory of the ancient burial ground may have staved off some early development, though limited road access to the fields more likely explains the lack of settlement up to the seventeenth century.2

The Franciscan abbey of St Clare without Aldgate was founded in or by 1293 on the east side of the Minories, which takes its name from the abbey’s nuns, who were known as Minoresses. Fields to the east, which came to be called Homefield, Homefield (described as forty acres in 1343 and fifty acres in 1472), pertained to the Manor of Barnes (or Bernes), a major part of lands held from the Bishop of London by the Trentemars family from the twelfth century, with a large house on the east side of the Minories south of the abbey that was called Bernes in 1395 when an interest in the property was inherited by John Cornwaleys who subsequently consolidated control of the manor. This land in Whitechapel is said to have been used by the Minoresses as a convent garden or farm, that is market garden, before the dissolution of the abbey in the 1530s. Sir John Cornwallis thereafter leased the fields to Rowland Goodman (d. 1544), a merchant and citizen Fishmonger, and his wife Anne. Thomas Goodman (b. 1528), a son and heir, followed with a new Cornwallis lease. It was later said by John Stow (1525–1605), who recalled fetching milk from Goodman’s farm in his youth, that the land was used for grazing horses. It seems that it was from 1574, under the watch of Rowland’s grandson, also Thomas Goodman (d. 1606), that northern and southern sections of the open fields close to Rosemary Lane (Hog Lane up to about 1600) and Whitechapel High Street were divided into parcels, leased and converted into garden plots, tenter yards, and bowling alleys. The manor of Barnes was conveyed from Sir Thomas Cornwallis to William Bromefield in 1560 and then from Catherine Bromefield, his widow, to Thomas Goodman in 1594 when it entailed fifty-four messuages, seventy-two gardens, twenty cottages, a windmill and seventy acres of pasture across Whitechapel, extending into the parish of St Botolph Aldgate. Referred to as ‘Mr Thomas Goodman, esq.’ at the time of his death in 1606, he had profited from development to the extent that he ‘lived like a gentleman thereby’; he had moved out of the City to West Ham, a favoured residence for wealthy City men.3

Around five acres to the south of Whitechapel High Street and north of what later became Alie Street came to be held by Edward Gaunt (d. c.1619). Subdivided as gardens, this property descended to his daughter Katherine (d. 1624), and then to her husband Anthony Botley.4

The main manorial holding was settled on the children of Thomas Goodman the younger, though his widow Beatrice disputed her claim. Two of the children, William Goodman and Anne Carey, sold their lands in 1628 to a former Lord Mayor of London and Prime Warden of the Fishmongers’ Company, Sir John Leman (1544–1632). This estate, now called Goodman’s Fields, then consisted of ten messuages, forty cottages, and forty acres of pasture. It included the capital messuage of Barnes, on the west side of what would become Mansell Street. Leman was the grandson of a refugee from Flanders, whose surname was likely Le Mans. A merchant who moved from Suffolk to London, John Leman initially prospered in the capital as part of a cartel that cornered trade in butter and cheese. He later involved himself in the early ventures of the East India Company. His success enabled him to purchase several estates including Rampton, Cambridgeshire, and Warboys, Huntingdonshire. Unmarried on his death in 1632, Leman bequeathed his estates to his nephew William Leman, a Cheapside linen draper, whose marriage in 1628 to Rebecca Prescot, the daughter of Edward Prescott, a citizen Salter, was to be commemorated in the naming of Prescot Street. A plot of land within Goodman’s Fields was in fact also gifted to Christ’s Hospital, John Leman having acted as its President since 1618. Even in the mid-eighteenth century, rents from land west of Leman Street were used to fund the Hospital. With his uncle’s substantial inheritance, William Leman purchased the seat of Northaw, Hertfordshire, where he lived from 1632 until his death in 1667. Said to have financially supported the future Charles II during his exile, William Leman secured a baronetcy in 1665. This passed to his son, also William Leman (1637–1701).5

In 1655, this younger (Sir) William Leman married Mary Mansell, the daughter of Sir Lewis Mansel and granddaughter of Henry Montagu, Earl of Manchester. Mary’s pedigree was recognised in the naming of their only son, Mansel, and in the most westerly street to be laid out on Goodman’s Fields. Mansel Leman’s wife, Lucy Alie, the daughter of Richard Alie, an Alderman of London, accounts for a further street name. Mansel Leman died as a young man in 1687 and the Leman estate was equally divided in 1701 between one of his three sisters, Theodosia (who married Lewis Newnham of Maresfield, Sussex), and his son, Sir William Leman III (1685–1741). In 1715, William Perris, of St Dunstan in the West, purchased a copyhold interest in Goodman’s Fields, ‘alias Leman’s Fields’, having also involved himself north of Whitechapel High Street in relation to the Goulston estate in 1702.6

Goodman’s Fields were only lightly occupied for most of the seventeenth century, though use for the stretching of cloth on tenters was long-standing, spanning from at least the 1570s until the 1750s. In 1614 Goodman’s Fields was referred to in relation to the spinning of twenty tons of hemp intended for rigging a ship bound for the East Indies. In 1656, several inhabitants of Goodman’s Fields complained of the danger posed to their houses by proximity to the gunpowder stores of local ships’ chandlers. Sir Christopher Myngs, a buccaneering naval officer who had helped to secure control of Jamaica, is said to have died in 1666 at his seven-hearth house in Goodman’s Fields.

Ownership of at least part of the five acres north of the line of Alie Street that were subdivided as gardens had passed by the 1670s from Anthony Botley to Sir Henry Hudson (_c._1609–1690) of Melton Mowbray, who had a baronetcy created in 1660 and who held properties across London’s eastern suburbs. Matthew Penn, a nurseryman, occupied this land, known as Penn’s Garden. The Lemans had at least three other garden plots in this area that were leased ‘with premises thereon’ to William Kendrick, a citizen Cooper, in 1663.There were some buildings, notably an array of what were probably workshops and warehouses on the north side of what was to become Alie Street, to some extent occupied by silk throwsters. However, in the 1670s Goodman’s Fields was still for the most part open fields, gardens and ropeyards.7

Framework of first development

The second Sir William Leman, who inherited in 1667, was responsible for the first wave of proper development. The value of the land for building would have been obvious, with comparative evidence at hand in large mid seventeenth- century developments in Spitalfields and Shadwell, let alone smaller more local initiatives. Strype indicated that some building work at least was underway in 1678 and William Morgan’s map of 1682 shows that what were to become Mansell Street, Alie Street, Lambert (later Lambeth) Street and Chamber Street had been laid out around the margins of the property, with what would be Prescot Street an internal addition as an eastwards continuation of Goodman’s Yard. This layout indicates coherent estate planning on an impressive and ambitious scale. Leman aside, whose mind, energy and designs lay behind this overarching ‘Scheme’, as he referred to it, remains unknown, but it was recorded at the time that Leman, who was granting major building leases in 1682, intended ‘to make great Improvements … by many Houses and Erections to be built … by Lease to be Granted to other persons at long terms of years at small yearly rents under several covenants and agreements for building’.8

There were already some new houses on Mansell Street by 1682, when Leman leased large parts of the fields to John Hooper and John Price. By 1684 Sir Thomas Chamber had seen off and supplanted Price. Hooper laid out Leman Street and lesser streets to its east before his early death in 1685. His leases were taken over by John Bankes and Sir Stephen Evance. Chamber inveigled William Chapman into building Prescot Street’s houses in 1685–9, along with some on Chamber Street. Leman Street was slower to be built up, Alie Street even more so. Thomas Neale had initiated development of the gardens north of Alie Street by 1682, but he sold up and Edward Buckley saw through building on this land from 1683.

John Hooper was a timber merchant and citizen Draper, probably from Devon. As the principal developer of the area east of and including Leman Street up to 1685 he undertook some work directly. He laid out Hooper’s Square, Rupert Street and Lambert Street. Lambert was his well-connected wife Margaret’s surname before their marriage in 1679.

John Bankes (_c._1652–1720) was another timber merchant, a major importer, probably of Scandinavian wood. From 1685 he had former Hooper property on both sides of Leman Street, also on Rupert Street and Hooper’s Square; he had directly overseen building under Hooper, contracting tradesmen at particular rates for brickwork and carpentry. Bankes is known to have worked with Nicholas Barbon in the 1680s on Duke Street in St Margaret’s, Westminster. After 1698 he was active as a builder in Holborn and he rose to become Master of the Haberdasher’s Company in 1717. However, his will recorded nothing more by way of property in Whitechapel than a leasehold estate at George Yard on the north side of Whitechapel High Street.9

Sir Stephen Evance (or Evans) benefitted from being a creditor of Hooper’s. He was assigned forty-five houses and much undeveloped land on the eastern side of Goodman’s Fields in 1686. Born in Virginia in 1652, Evance had amassed a fortune through finance, having arrived in London aged fourteen to serve as an apprentice in a goldsmith’s shop. From the 1680s he involved himself in a range of entrepreneurial schemes, as a banker, bullion dealer and Hudson’s Bay speculator, rising to be a prominent government financier after 1688. Evance’s political and Crown service led to a knighthood in 1690, and he was an MP from 1690 to 1698. He was also a director of the Royal African Company, and thus profited from the slave trade. His business exploits were not without controversy at the time. He was censured for the illegal importation of 100 bales of raw silk worth £14,718 in 1693, and accused of bribery by directors of the East India Company in 1695. A swift fall from grace ensued. Having been declared bankrupt in January 1712, Evance committed suicide in March, dying unmarried and childless. His involvement in developing Goodman’s Fields appears to have been his only activity in building speculation.10

John Price, a citizen Skinner, took several sixty-two-and-a-half-year leases from William Leman in June 1682, agreeing to pay an annual rent of £1,200 for four building plots on the south side of Prescot Street and two on the north side. He also took property on the west side of Leman Street and what had been Kendrick’s three garden plots north of the line of Alie Street where with Thomas Neale he formed and built on Red Lion Street. Price gained financial backing from Chamber, who then, despite further backing from John Methuen (probably the lawyer who was to become Ambassador to Portugal and prime mover of the treaties of 1703 that established Anglo-Portuguese alliance and free trade), forced Price into bankruptcy for non-payment of interest in 1683–4 and took over much of his property.

Sir Thomas Chamber (sometimes Chambers, d. 1692) had been the East India Company’s Agent in Madras from 1658 to 1662, when he was dismissed for insubordination. He stayed on, gained exoneration in 1665, and returned to England to be knighted in 1666. He bought the manor of Hanworth in Feltham, Middlesex, in 1670. Having displaced Price, Chamber was substantially involved with development in Goodman’s Fields from 1685. He collaborated with, or rather manipulated, William Chapman, a carpenter, in the building of houses on Prescot Street and Chamber Street in 1685–9. Chamber is said to have contracted Chapman to build sixty-six houses on Prescot Street, working from west to east along almost its whole length in stages, promising to advance all money needed, and to buy the houses himself if Chapman could not sell them. Chapman got the first ten carcasses up, and was then obliged to reassign the properties to Chamber as a condition of a further loan to enable him to complete. Chamber let the houses and received the rents, while Chapman spent more than he had been loaned. Drawn in and in debt, Chapman was allegedly induced to repeat this several more times, always finding himself obliged to use his own money to complete, and giving up the rents to Chamber in what was recognised at the time as an extraordinary process. Chapman ended up with large debts to many creditors, which Chamber promised to settle in exchange for Chapman signing a general release. He did sign, but Chamber reneged and Chapman absconded.

Around the same time Chamber was engaged in other property speculations, in Shadwell, Wanstead, Montgomeryshire, and on Cornhill in London. When he died in 1692 his only son, Thomas Chamber (usually Chambers, 1668–1736) inherited his extensive estate, large tracts in west Middlesex and property in the City, Westminster, Clerkenwell, Shoreditch, Goodman’s Fields, Shadwell, West Ham, Stratford, Barking and Yorkshire. His widow, Elizabeth, was given use of the manor house in Hanworth and a mansion on Prescot Street.11 The younger Thomas Chambers continued to prosecute development in Goodman’s Fields, including frontages on Leman Street, as well as on Rosemary Lane. He married Lady Mary Berkeley, the daughter of Charles Berkeley, the Second Earl of Berkeley. After his death at Hanworth, it was reported that his two daughters would inherit very great fortunes.12

Thomas Neale (1641–1699), the prominent courtier and speculator, was on the scene by 1681, around when he bought Penn’s Garden from Sir Henry Hudson and planned the laying out of streets and houses between Alie Street and Whitechapel High Street. Neale had acquired great wealth and lands in Shadwell through marriage in 1664, and it was in Shadwell that he cut his teeth as a speculative developer. He had no doubt caught wind of Leman’s intentions for Goodman's Fields and seen an opportunity. Through an agreement of April 1682 he combined with Price in forming Red Lion Street, crucial to the opening up of his Whitechapel property, and he may have started on other preparatory work. However, perhaps foreseeing difficulties, he bailed out later in 1682, prevailing on Edward Buckley, a wealthy citizen Brewer who had been a hearth- tax farmer, whose business was in Old Street and who had residences in St Giles Cripplegate and Putney, to buy his Whitechapel property. One of several brewers to invest in Nicholas Barbon’s Fire Office around 1681, Buckley acquired an estate in St Margaret’s Westminster in 1682 where he or his son became entangled with Barbon’s development of Charles Street and Duke Street. In Whitechapel it transpired that Red Lion Street could not be knocked through to Whitechapel High Street until about 1685, and litigation arising from Price’s debts that chuntered on thereafter led Grace Andrews, proprietor of the newly rebuilt Red Lion Inn, to erect posts and rails across the north end of Red Lion Street that were up to at least 1687, a blockage that must have dampened enthusiasm for investment at the north end of Goodman’s Fields.

Buckley died in August 1683, his son and heir being Edward Buckley (1656–1730), whose inheritance included the brewery, residences and Whitechapel estate. Buckley consolidated the Penn’s Garden holding, seemingly with what had been Price’s garden plots and others perhaps, to permit the laying out of a close grid of roads that included Buckley (soon corrupted to Buckle) Street, Colchester Street (later Braham Street), and Plough Street, all largely built up by the 1690s. He granted long leases, including of ninety-nine years, as to Timothy Salter, a Whitechapel bricklayer.13

The paving of Goodman’s Fields’ roads was completed in 1691, with Red Lion Street (north) and White Lion Street (south) providing important links to Whitechapel High Street and Rosemary Lane as continuations of Leman Street. Archaeological excavations on what was the east side of Red Lion Street have identified a large seventeenth-century brickfield. By 1694 many frontages were built up with houses and occupied, the east side of Mansell Street solidly so with twenty-three mostly substantial houses, Prescot Street and Lambert Street very largely, with seventy-two and eighty houses respectively, and Buckley’s northerly lands extensively with well over a hundred mostly small houses. Leman Street and Alie Street were yet to fill up. Somerset Street connected Mansell Street to Aldgate High Street at the parish boundary.

Edward Hatton remarked on the spaciousness of ‘Aly’, ‘Lemon’, Mansell and Prescot streets in 1708.14 These four main streets roughly formed a large square with houses addressing the streets on both sides, those on the inner sides concealing an unusually extensive central enclosure, not a garden square in the usual sense, but fashioned for both pleasure and for cloth-stretching as a tenter ground. It was to have been called Leman’s Quadrangle, but the name did not stick. The space was surrounded by a tree-lined carriageway entered by a single gate from Prescot Street and to some extent it functioned as mews.

The development of plots backing onto the tenter ground was of a consistently high standard – these were Whitechapel’s best houses. Leases appear generally to have been for sixty-one years or thereabouts. They specified that houses should be brick-built, contiguous and built according to a ‘Scheme’, of which nothing is known. Heights, wall thicknesses and timber scantlings were to follow the specifications for houses of the second ‘Rate’ (‘Sort’) in the Act of 1667 for rebuilding the City of London, that is those fronting streets ‘of note’. Lessees were obliged to pave eight-foot wide footpaths and the streets in front of their takes. Little more is known of the particulars, the processes of estate development remain largely obscure.

It is evident that Mansell Street’s east side and all of Prescot Street were systematically and speedily developed, exceptionally regular for their time, though not standardised, there being considerable variation from house to house. Many East India Company captains, traders with North America, cloth merchants, silk throwsters, and corn factors took up residence in double- fronted mansions on Mansell Street, Alie Street’s south side, Leman Street’s west side, and Prescot Street. Goodman’s Fields had good access to the Thames and the naval depot on the later Royal Mint site; a number of early occupants appear to have had connections to the provisioning of ships and the navy, though such residence was often brief if not transitory. The mercantile and international character of the area’s inhabitants was strongly represented in its early Jewish population, Sephardic and with strong roots in Bevis Marks Synagogue. Dr William Payne, the vicar of St Mary Matfelon from 1681 to 1697, based himself on Alie Street, where a Particular Baptist congregation appears to have gathered from 1698. In 1720 Strype characterized Goodman’s Fields as ‘fair Streets with very good brick Houses well inhabited by several Merchants, and Persons of Repute’.15

Development was far from complete and there was not uniformity. Close to the bustle of Whitechapel High Street, Alie Street lagged, many of its south-side frontages remaining open into the 1720s when Samuel Hawkins (see below) appeared on the scene. Alie Street’s north side remained in parts unreconstructed from the arrangements that antedated 1680. There was also a large gap on the east side of Leman Street until the early 1720s, with completion of that street’s west side perhaps coming no earlier. Buckley had kept an orchard off Red Lion Street. Elsewhere on his holding, open ground called Deans Garden, accessed via Buckle Street, was being used as a riding ground in 1714.

Building work was gradual and ongoing. Gaps continued to be filled under the ownership of Sir William Leman III in the 1730s and beyond when there was work on the north side of Alie Street. Rebuilding at the expiry of first-phase leases was being undertaken on Prescot Street in the 1740s. Away from the prestigious frontages, sugarhouses began to appear in the first decades of the eighteenth century and some larger gardens were built over. There were a number of ‘disorderly’ or ‘Bawdy’ houses in Goodman’s Fields, keepers of which were made to stand in a pillory on Alie Street in 1753.16

Descent of the Leman Estate

Sir William Leman III died childless in 1741, survived by his widow Anna Margareta. His moiety of the Goodman’s Fields estate passed to Richard Alie, a nephew, who took the surname Leman by Act of Parliament in 1745. Richard Leman, however, suffered from gout and did not long survive his uncle, dying in 1749 with no direct heir. The estate fell to his unmarried sister Lucy Alie, who then died in 1753. These misfortunes led to the endorsement of John Granger (who was no relation) to inherit by Act of Parliament on condition he also take on the Leman surname. John Granger Leman’s marriage to Elizabeth Worth, the daughter of East India Commander Captain Philip Worth, was childless. He died in 1779 and two years later his widow Elizabeth married William Strode of Loseley House, Surrey, who assumed claim to the Leman estate. This marriage was also childless and Elizabeth died in 1790. Strode’s second marriage to Mary Finch (née Brouncker) also ended without issue, leading to sale of this half of the estate after Strode’s death in 1809 and consequent litigation. There were auctions of freeholds in 1814 and 1831 and legal complications regarding the remnants of this holding wittered into the 1850s.17

Strode’s portion constituted only half of the original estate. Rights to the other half had passed down through Theodosia (née Leman) and Lewis Newnham to their daughter, Elizabeth Newnham (d. 1767), and son, John Newnham (d. 1765), of Maresfield in Sussex, cousins of Sir William Leman III_. _Division of the estate between John Granger Leman and the Newnhams was confirmed by Act of Parliament in 1756. Following another Act of 1776 enabling a sale, Edward Hawkins bought half the Newnham moiety of the copyhold estate in 1779 and his brother and heir, Samuel Hawkins, bought the other half in 1787.18

Edward Hawkins (1723–1780) was the son of Samuel Hawkins (1690–1771), Master of the Carpenter’s Company in 1745 and a ‘Builder of Goodman’s Fields’ according to his will, who was a major figure in the last stages of the development of Goodman’s Fields. On Samuel’s marriage in 1721 it appears that he moved to Whitechapel, taking a house in Chamber Street, and responsibility for the construction of a number of houses nearby, including on the south side of Alie Street where a row datable to the 1720s survives. He was also active in Spitalfields. He moved to a large house on Leman Street in the 1750s, from where his sons, Edward and Samuel Hawkins (1727–1805), extended their local reach and influence. Edward was another carpenter who became surveyor to the London Hospital, and Samuel, who was in business as a silk throwster, was a magistrate, treasurer of the parish charity school, and chairman of the pavement commissioners for Whitechapel’s Church Lane from 1783. Edward married Ann Schumacker, from a prosperous Leman Street family of German sugar refiners. They had no children so when Edward died in 1780 his brother Samuel took control of the Goodman’s Fields property.

Meanwhile, Major Rohde (1744–1819), another local sugar refiner, had married Mary Hawkins, of Newnham, Gloucestershire, in 1776. She appears to have been the granddaughter of the elder Samuel Hawkins’s brother, Thomas Hawkins (d. 1776), also of Newnham, who had a coalyard on the Severn shipping coal to London. On Samuel Hawkins’ death in 1805, his Goodman’s Fields properties descended, in trust via his sister-in-law Ann (née Schumacker) Hawkins (d. 1812), to his cousin and Thomas’s son, Edward Hawkins (1749–1816), a banker in Neath, Glamorganshire, and then to his son, Edward Hawkins (1780–1867), a keeper of antiquities at the British Museum, who married Eliza Rohde in 1806. The next heir was their son, the architect Major Rohde Hawkins (1821–1884). Parts of the Hawkins’ estate not already sold off were auctioned in 1919.Edward and Samuel Hawkins were lessees of the tenter ground from 1775. Their purchases of the Newnham moiety of the estate thereafter gave them full control of the northern half of this undeveloped land. The southern half had been acquired by the Scarborough family after Strode’s death in 1809. Access roads were formed in 1814–15, which led to the creation of St Mark’s Street, but development that included St Mark’s Church did not follow until the 1830s. The former tenter ground had been built up with rows of humble terraced houses by 1851.19

-

John Strype, A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster, vol.2/4_, 1720, p.23: Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England), _An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in London, vol.3: Roman London, 1928, p.157: Agas map, _c._1561: Faithorne and Newcourt map, 1658 ↩

-

www.lparchaeology.com/prescot/journal/: P. Thrale, ‘Goodman’s Fields, London E1: An archaeological evaluation report’, Museum of London Archaeology unpublished report series, 2008: G. Hunt, C. Morse, ‘Archaeological Evaluation Report, Prescot Street, London E1’, 2006 ↩

-

John Stow, A Survey of London, 1603, C. L. Kingsford (ed.), 1908, vol.1, p.126; vol.2, p.288: E. M. Tomlinson, A History of the Minories, London, 1907: G. S. Fry (ed.), Abstracts of Inquisitiones Post Mortem For the City of London: Part 1, 1896, pp.95-110: The National Archives (TNA), C78/4/51; C8/11/36; CP25/2/262/36; CP25/2/526/4: Calendar of the patent rolls preserved in the Public Record Office, Edward VI, vol.5 (1547–53), 1926, p.332: T. F. T. Baker (ed.), A History of the County of Middlesex, vol.11: Stepney, Bethnal Green, 1998, pp.13–19: Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives (THLHLA), P/SLC/1/17/20: London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), P69/BOT2/A/015/MS09222/001: Ancestry ↩

-

TNA, WARD5/26: James Bird and G. Topham Forrest (eds), Survey of London, vol.8: The Parish of St Leonard, Shoreditch, 1922, p.10 ↩

-

TNA, C8/11/36; PROB11/161/375; PROB11/325/275; PROB11/133/638: Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies (HALS), DE/X22/28978: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB) sub Leman: www.londonroll.org: LMA, Land Tax Returns (LT); Middlesex Deeds Registry (MDR): History of Parliament Online (HoPO) sub Leman: Henry Stevens, The Dawn of British Trade to the East Indies as recorded in the Court records of the East India Company 1599–1603, 1886, p.254: Rosemary Weinstein, ‘The Making of a Lord Mayor, Sir John Leman: The integration of a stranger family’, Proceedings of the Huguenot Society, vol.24/4, 1986, pp.316–24: A. Wright and C. P. Lewis (eds), A History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely, vol.9: Chesterton, Northstowe, and Papworth Hundreds, 1989, pp.212–14: W. Page, G. Proby, S. Inskip Ladds (eds), A History of the County of Huntingdon, vol.2,_1932, pp.242–6: W. Page (ed.), _A History of the County of Hertford, vol.2, _1908, pp.357–60: D. J. Keene and Vanessa Harding, _Historical Gazetteer of London Before the Great Fire Cheapside; Parishes of All Hallows Honey Lane, St Martin Pomary, St Mary Le Bow, St Mary Colechurch and St Pancras Soper Lane, 1987, pp.270–5 ↩

-

MDR1715/2/32–3: Parliamentary Archives (PA), HL/PO/JO/10/6/102/2266: THLHLA, P/SLC/1/17/20: Page et al (eds), Huntingdon, pp.242–6: Page (ed.), Hertford, pp.357–60 ↩

-

TNA, C2/Jasl/L11/35; C7/58/2; C8/404/37; PROB11/401/31: LT: Ancestry: W. Noel Sainsbury (ed.), Calendar of State Papers Colonial, East Indies, China and Japan, _vol.2, _1513–1616, 1864, pp.279–89: M. A. E. Green (ed.), Calendar of State Papers Domestic: Interregnum, 1656–7, 1883, pp.146–79: W. A. Shaw (ed.), Calendar of Treasury Books, vol.3, 1669–1672, 1908, pp. 927–38: M. A. E. Green (ed.), Calendar of State Papers Domestic: Charles II, 1664–5, 1863, pp.288–304: ODNB sub Myngs: T. F. T. Baker (ed.), Victoria County History, A History of the County of Middlesex, vol.11: Stepney, Bethnal Green, 1998, p.173 ↩

-

TNA, C11/49/29; C10/544/6 ↩

-

British History Online, Four Shillings in the Pound Assessments, 1693–4 (4s£): TNA, C5/79/43; C7/569/9; PROB11/452/437: haberdashers.co.uk/our-vaults: Frank Kelsall and Timothy Walker, Nicholas Barbon 1640–1698, forthcoming 2021, pre-publication typescript ↩

-

HoPO sub Evance: ODNB sub Evance: Ancestry: 4s£: TNA, PROB11/573/418: Journals of the House of Commons, 12 Feb 1699, p.197: British Mercury, 5–7 March 1712: William A. Shaw, Calendar of Treasury Books, vol.7, 1681–1685, 1916, p.939: Stephen Quinn, ‘Gold, silver, and the Glorious Revolution: arbitrage between bills of exchange and bullion’, Economic History Review, n.s., vol.49/3, 1996, pp.473–90: Agnes C. Laut, The Conquest of the Great Northwest, 1908, pp.193,289–91 ↩

-

TNA, C5/187/11; C5/148/42; C7/58/2; C7/58/14; C7/58/2; C10/225/21; C10/213/24; C7/58/50; C7/64/2; PROB11/408/402; PROB11/490/348: LMA, MDR1715/2/32–3; LMA/4245/01/034: Victoria County History: A History of the County of Middlesex, vol.2, 1911, pp.314–9: Henry Davison Love, Indian Records Series: Vestiges of Old Madras, 1640–1800, vol.1, 1913, pp.199–204 ↩

-

London Evening Post, 17–20 Jan 1736, p.1: General Evening Post, 17–19 July 1735, p.1: LMA, LMA/4245/02/010 ↩

-

TNA, C5/99/23; C7/58/2; C8/404/37; C10/225/21; PROB11/638/2; PROB11/374/202: LMA, ACC/0349/301: Joseph Morgan, The New Political State of Great Britain, 1730, p.326: ODNB sub Neale: Ancestry: Frank Kelsall and Timothy Walker, Nicholas Barbon 1640–1698, forthcoming 2021, pre-publication typescript ↩

-

Edward Hatton, A New View of London, vol.1, 1708, pp.2,46,51,65 ↩

-

Strype, Survey of London, _vol.2/2, p.28: W. J. Hardy (ed.), _Middlesex County Records. Calendar of Sessions Books 1689–1709, 1905, pp.26–105, passim: 4s£: Universal Spectator, 12 April 1732: Historic England, Greater London Historic Environment Record, ELO10294 ↩

-

LMA, ACC/0349/302: 4s£: Mawer: Church of England Record Centre, MS2724, MS2750/68, MS2716: TNA, P/CRV/9: MDR: THLHLA, cuttings 022 ↩

-

TNA, PROB11/771/375; PROB11/805/33; PROB11/1502/116: HoPO sub _Strode: HALS, DE/X22/28997; DE/X22/29006: THLHLA, P/SLC/1/20/34/1–2; P/SLC/1/21/1; LC10995: PA, HL/PO/PB/1/1807/47G3s2n207: _The Jurist, vol. 8/1, 1845, pp.14–15: Page et al (eds), Huntingdon, pp.242–6 ↩

-

East Sussex Record Office, SAS/AB/1098: TNA, C13/652/9;C13/920/9; C13/986/29; C13/987/1 ↩

-

West Sussex Record Office, SAS-F/346: MDR: LMA, P93/MRY1/092, p.19: TNA, C13/920/9; C13/986/29; C13/987/1; PROB11/1026/83; PROB11/1062/209; PROB11/1436/196; PROB11/1531/180; PROB11/1579/122; PROB11/1760/55; PROB11/1803/193; D2957/215/16; IR58/84815/3245; /84816/3207–20; /84823, /84829–31, /84834, /84839–40, passim: THLHLA, L/SMW/C/4/1: Richard Horwood's maps of London, 1792–1819: Ordnance Survey maps: Estates Gazette, 25 Oct 1919, p.558: F. H. W. Sheppard (ed.), Survey of London, vol.27: Spitalfields and Mile End New Town, 1957, pp. 245–51: LT: Ancestry: Electoral Registers ↩

Goodman's Fields redevelopment, 2002 to 2020

Contributed by Survey of London on June 5, 2020

In 2002 the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) submitted an outline scheme for redevelopment of the whole site bounded by Alie Street, Leman Street, Gower’s Walk and Hooper Street. Prepared by Sheppard Robson, architects, it proposed reconstructing the NatWest Management Services Centre’s operations building as glass-faced offices and demolishing the office blocks to the north. Two quadrangles of flats were proposed, to the north-east on Alie Street and to the south on Hooper Street. At the north-west corner a new garden (Leman Square) would provide access to the recast operations building and be flanked by blocks of shops and offices on Alie Street and Leman Street. The former CWS headquarters at 99 Leman Street was to be refurbished as flats, while only the façade of the adjacent 75 Leman Street was to be retained in front of new buildings arrayed around a space called Goodman Square. The scheme, which would not have risen higher than eight storeys, was gradually fleshed out and a section 106 agreement provided for twenty-five per cent ‘affordable’ housing (rented and shared ownership).

In the event only the southern part of the Sheppard Robson plan was executed. It took shape on the north side of Hooper Street in 2006–7 as City Quarter, comprising Times Square and 120 Gower’s Walk, four separate five- and six- storey blocks (203 flats) enclosing a garden, with Christopher Court, forty- five more flats in a similar L-plan block to the west adjoining the back of the former CWS headquarters (99 Leman Street), now refurbished as Sugar House for forty-two more flats. The north and east blocks (116 flats) were reserved for key workers, ‘affordable’ rent and shared ownership. The design was typical of its time, bar-code style, with windows offset on alternate floors, glazed cantilevered balconies, and ceramic cladding, light-grey with vari- coloured strips to the set-back top floors.1

In 2005, in a move away from ‘non-core operations’, RBS had disposed of numerous London properties, including the remaining parts of the Goodman’s Fields site, to Morgan Stanley Real Estate Funds (MSREF).

Here MSREF’s first development partner was Omega Land, a wholly owned subsidiary led by RBS’s former head of development. By 2007 Omega was reducing its stake in Goodman’s Fields and gradually being taken over by Exemplar Properties. London’s planning landscape had changed radically following the loosening of restrictions on tall buildings in the London Plan of 2004, since when permissions had been granted for several tall buildings on sites close to Goodman’s Fields.